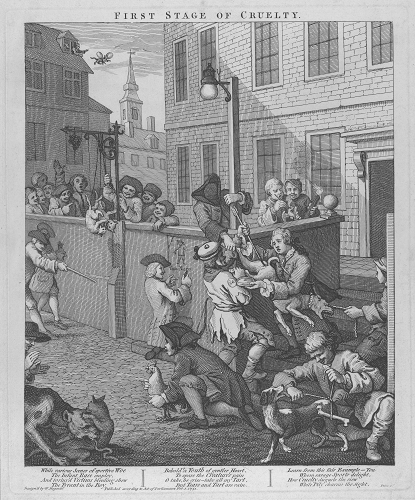

The First Stage of Cruelty

1750/1

14” X 11 5/8” (H X W)

View the full resolution plate here.

In plate 1, Tom Nero, the “hero” of the series is pictured as the lovely child shoving the arrow into the anus of a dog (the dog’s revenge for this act is demonstrated in plate 4). Other children stage an impromptu and sparsely attended cockfight. Various cruelties are being visited upon cats: two suspended cats attack each other; an experimental flying attempt involves strapping wings to a cat; a dog viciously attacks yet another cat. One boy prophetically writes Nero's name under the picture of a hangman. Boys cruelly burn out the eyes of a bird. Only one kind boy attempts to soothe the dog’s torment by offering him a treat.

Jarrett comments that this scene "lies at the very core of the English idea of pleasure" with "a fight to the death combined with the chance to gamble” (England 175). Thus, the boys are merely mimicking accepted behavior. Furthermore, there is a distinct lack of parental guidance in the scene. Although Tom bears the insignia of a local charity school, there are no adults in attendance here. As in "Gin Lane," there is no one here to model good behavior or to be alarmed at these obvious red flags to further bad behavior: their violence will go unchecked and will blossom into something quite deadly—both on an individual and on a potentially national level. Importantly, Tom is not the only child participating in these tortures, but he is the only one whose fate we will watch unfold

The First Stage of Cruelty

Paulson, Ronald. Hogarth’s Graphic Works. (1965)

CAPTION:

While various Scenes of sportive Woe

The Infant Race employ,

And tortur'd Victims bleeding shew

The Tyrant in the Boy.

Behold! a Youth of gentler Heart,

To spare the Creature's pain

0 take, he cries-take all my Tart,

But Tears and Tart are vain.

Learn from this fair Example-You

Whom savage Sports delight,

How Cruelty disgusts the view

While Pity charms the sight

The central figure is the “Tom Nero” whose fortune is predicted in chalk on the balustrade wall. He has a metal badge on his arm, “St G”—St. Giles’ Parish. The idea of the punishment he is inflicting on the dog may derive from Callot’s Temptation of St. Anthony, where one of the fiends thus worries the monster who bears him through the air (Brechtel, pl. 222; but cf. the punishment of the horse in Hogarth’s Hubridas and the Skimmington). The young gentleman, who (as the pious verses underneath tell) offers his tart to save the dog, is said to be Hogarth’s compliment to the prince, George William Frederick, afterwards George III (aged thirteen; J. Ireland, 2, 61); if so, it was well timed. In March George’s father died, and in April he became Prince of Wales. The boy behind Nero is holding a cock, so that the boy at left rear can use it as a mark for his stick. Behind him is a boy with a second cock. This sport was known as “throwing at cocks.” On the other side of the balustrade a boy is blinding a bird with a hot wire, heated in the flame of a torch held by his friend, a link boy. In the upper left corner of the print two boys are throwing a cat out a garret window to see if, with wings attached, it can fly (211-212).

The First Stage of Cruelty

Shesgreen, Sean. Engravings by Hogarth. (1973)

In this print, a number of children visit upon domestic pets the type of savagery traditionally attributed only to animals. They torture them and train them to maim and kill each other. In the center of the scene an orphan boy called Tom Nero and two friends plunge an arrow (tipped with alcohol?) into the anus of a dog. A well-dressed middle-class child, possibly the dog’s master, attempts to stop the boys by force and bribery. To the left of this group a boy sketches a prophetic stick drawing of “Tom Nero” hanging from a gallows. Above Nero a grinning linkboy watches with sadistic joy as his companion burns out the eye of a captive bird to satisfy his curiosity.

Across from them a group of cheering children watch two suspended cats claw each other in fright. Below them a boy aims a stick at an unsuspecting cock held in position by another youth. To the left a man has set his dog upon a cat while close by a youth ties a bone to the tail of a pup that licks his hand gratefully in response. From a garret two people release a cat on artificial wings in an ill-fated attempt to make it fly (77).

The First Stage of Cruelty

Dobson, Austin. William Hogarth. (1907)

The Four Stages of Cruelty are a set of plates exhibiting the “progress” of one Thomas Nero, who, from torturing dogs and horses, advances by rapid stages to seduction and murder, and completes his career on the dissecting table at Surgeon’s Hall. They have all the downright power of Hogarth’s best manner; but they are unrelieved by humour of any kind, and are consequently painful and even repulsive. “The leading points in these as well as the two preceding prints,” says Hogarth, “were made as obvious as possible, in the hope that their tendency might be seen by men of the lowest rank. Neither minute accuracy of design, nor fine engraving was deemed necessary, as the latter would render them too expensive for the persons to whom they were intended to be useful.” These words should be borne in mind in considering them. . . . The price of the ordinary impressions was a shilling the plate, and an unsuccessful attempt was made to sell them even more cheaply by roughly cutting them on a large scale in wood (105-106).

The First Stage of Cruelty

Quennell, Peter. Hogarth’s Progress. (1955)

The lesson taught by the Four Stages of Cruelty is no less deliberately rammed home. Tom Nero, an undeserving Charity Boy, begins by torturing a stray dog, as the driver of a hackney carriage unmercifully thrashes his broken-down horse, murders a servant-girl whom he has previously seduced and persuaded to steal her master’s silver, and at last appears as a disemboweled corpse, exposed to the scientific brutality of the anatomists at Surgeons’ Hall (210).

The First Stage of Cruelty

Uglow, Jenny. Hogarth: A Life and a World. (1997)

in The Four Stages of Cruelty a boy foretells Tom Nero’s fate by drawing a gibbet on the wall (56).

Unsupervised, unloved children are fated. Tom begins his career of cruelty by torturing a dog. He is not alone, but is surrounded by the other boys suspending fighting cats from a rope, swinging sticks at cocks, blinding a dove with a heated wire, tying a bone to a starving dog’s tail, throwing a cat from a window to test its artificial wings. These urchins are no better than the rabid cur in the corner gnawing the entrails of a living cat. And through the well-dressed “gentler” boy (said to be based on the young Prince George) trying to extract the arrow from the dog’s rear, Hogarth suggests that their “betters” must show them the right way (501-502).

The First Stage of Cruelty

Paulson, Ronald. Popular and Polite Art in the Age of Hogarth. (1979)

[Fielding’s Enquiry] points out . . . that one of the causes of the poor’s thievery lies with the church wardens and overseers of the poor . . . who “are too apt to consider their Office as a Matter of private Emolument, to waste Part of the Money raised for the Use of the Poor in Feasting and Riot”—a point . . . implied in The First Stage of Cruelty by the St. Giles insignia on young Tom Nero’s arm and the absence of the St. Giles parish officers who should be looking after him (4).

Looking back, we have to see the first Stage of Cruelty as defined by the St. Giles Parish officers, and the second by the very decided presence of the bulky lawyers who are in fact responsible for the collapsed horse which Nero is beating (they have crowded in to save a fare). Thus we proceed to the grimly threatening constabulary of Cruelty in Perfection and the surgeon-magistrate of The Reward of Cruelty, those representatives of the law, the forces from above from whom Nero—as is finally made explicit in his “reward”—serves merely as someone who is not (to use Fielding’s phrase) “beyond the reach of . . . capital laws” (8).

The First Stage of Cruelty

Trusler, Rev. J. and E.F. Roberts. The Complete Works of William Hogarth. (1800)

This pathetic lesson of humanity is given by the poet of nature. Aiming at the same end by different means, our benevolent artist here steps forth as the instructor of youth, the friend to mercy, and advocate of the brute creation.

In the prints before us, an obdurate boy begins his career of cruelty by tormenting animals; repeated acts of barbarity sear his heart; he commits a deliberate murder; and concludes in an ignominious death. These gradations are nature, I had almost said inevitable; and that parent who discovers the germ of barbarity in the mind of a child, and does not use every effort to exterminate the noxious weed, is an accessory to the evils which spring from its baneful growth. To check these malign propensities, becomes more necessary from the general tendency of our amusements. Most of our rural and even infantine sports are savage and ferocious. They arise from terror, misery, or death of helpless animals. A child in the nursery is taught to impale butterflies and cockchafers. The schoolboy’s proud delight is clambering a tree—“To rob the poor bird of its young.”

Grown a gentle angler, he snares a scaly fry, and scatters leaden death among the feathered tenants of the air: ripened to manhood, he becomes a mighty hunter, is enamoured of the chase, and crimsons his spurs in the sides of a generous courser, whose wind he breaks in the pursuit of an inoffensive deer, or timid hare.

Let us suppose a disciple of Pythagoras to contemplate this print, how would it affect him? He could imagine it to represent a group of young barbarians, qualifying themselves for executioners; would raise his voice to heaven, and thank the God of mercy that he is not an inhabitant of such a country. This delineation of such scenes must shock every feeling heart, and their enumeration disgust even humane mind. Let us hope, for the honour of our nature and our nation, that they are not so frequently practised as when these prints were published.

The hero is this tragic tale is Tom Nero: by a badge upon his arm we know him to be one of the boys of St. Giles’s charity-school. The horrible business in which is engaged, let us hope, was never realised in this or any other country. The thought is taken from Callot’s “Temptation of St. Anthony.” A youth of superior rank, shocked at such cruelty, offers his tart to redeem the dog from torture. This Hogarth intended for the portrait of an illustrious personage, then about thirteen years of age; the compliment was rather coarse, but well intended. A lad chalking on a wall, the suspended figure inscribed “Tom Nero,” prepares us for the future fate of this young tyrant, and shows by anticipation the reward of cruelty.

Throwing at cocks might possibly have its origin in what some of our sagacious politicians call a natural enmity of France; which is thus humanely exercised against the allegorical symbol of that nation. A boy tying a bone to the tail of his dog, while the kind-hearted animal licks his hand, must have a most diabolical disposition. The two little imps are burning out the eye of a bird with a knitting-needle. A group of embryonic Domitians who have tied two cats to the extremities of a rope, and hung it over a lamp-iron, to see how delightfully they will tear each other, are marked with grim delight. The link-boy is absolutely a Lilliputian fiend. The fellow encouraging a dog to worry a cat, and two animals of the same species thrown out of a garret window with bladders fastened to them, complete this mortifying prospect of youthful depravity (133-134).

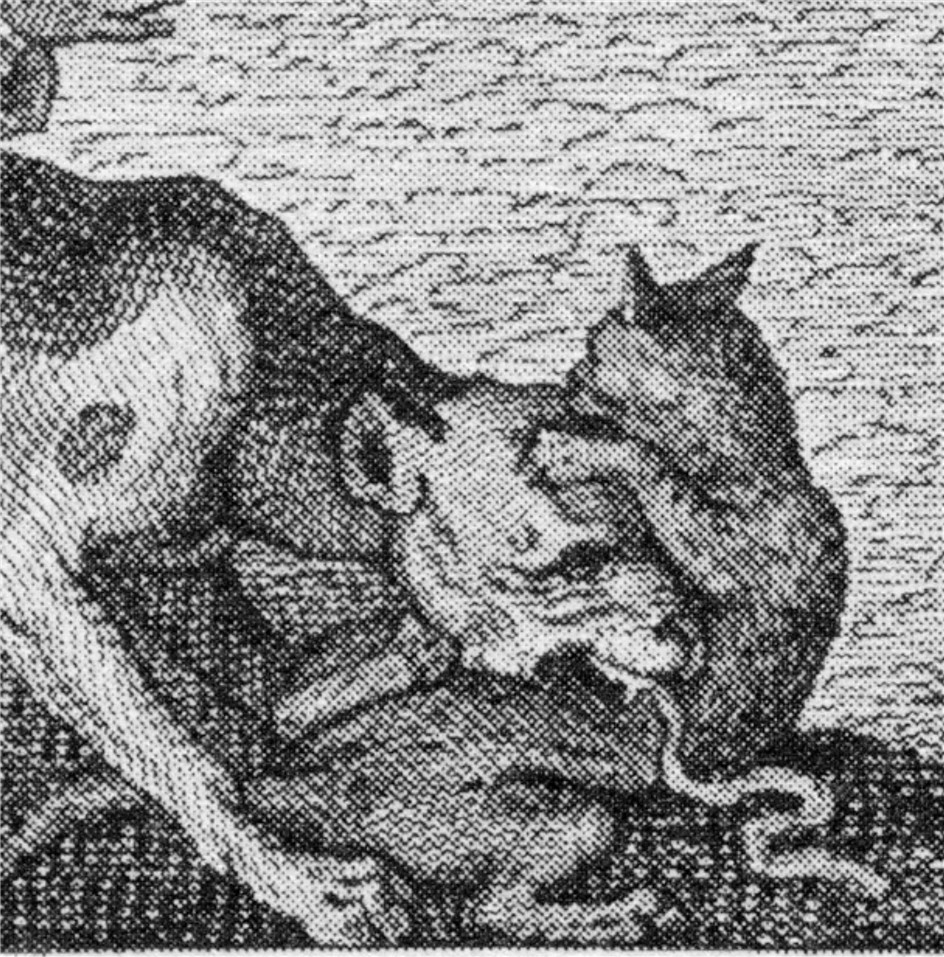

The First Stage of Cruelty: Dog Butt

In plate 1, Tom Nero, the “hero” of the series is pictured as the lovely child shoving the arrow into the anus of a dog (the dog’s revenge for this act is demonstrated in plate 4). Only one kind boy attempts to soothe the dog’s torment by offering him a treat.

Tom bears the insignia of a local charity school; there are no adults in attendance here. Importantly, Tom is not the only child participating in these tortures, but he is the only one whose fate we will watch unfold.

The First Stage of Cruelty: Dog Butt

Paulson, Hogarth's Graphic Works

The central figure is the “Tom Nero” whose fortune is predicted in chalk on the balustrade wall. He has a metal badge on his arm, “St G”—St. Giles’ Parish. The idea of the punishment he is inflicting on the dog may derive from Callot’s Temptation of St. Anthony, where one of the fiends thus worries the monster who bears him through the air (Brechtel, pl. 222; but cf. the punishment of the horse in Hogarth’s Hubridas and the Skimmington). The young gentleman, who (as the pious verses underneath tell) offers his tart to save the dog, is said to be Hogarth’s compliment to the prince, George William Frederick, afterwards George III (aged thirteen; J. Ireland, 2, 61); if so, it was well timed. In March George’s father died, and in April he became Prince of Wales (211-212).

The First Stage of Cruelty: Dog Butt

Shesgreen

In the center of the scene an orphan boy called Tom Nero and two friends plunge an arrow (tipped with alcohol?) into the anus of a dog. A well-dressed middle-class child, possibly the dog’s master, attempts to stop the boys by force and bribery (77).

The First Stage of Cruelty: Dog Butt

Uglow

Tom begins his career of cruelty by torturing a dog. . . . And through the well-dressed “gentler” boy (said to be based on the young Prince George) trying to extract the arrow from the dog’s rear, Hogarth suggests that their “betters” must show them the right way (500-501).

The First Stage of Cruelty: Dog Butt

Trusler

The hero is this tragic tale is Tom Nero: by a badge upon his arm we know him to be one of the boys of St. Giles’s charity-school. The horrible business in which is engaged, let us hope, was never realised in this or any other country. The thought is taken from Callot’s “Temptation of St. Anthony.” A youth of superior rank, shocked at such cruelty, offers his tart to redeem the dog from torture. This Hogarth intended for the portrait of an illustrious personage, then about thirteen years of age; the compliment was rather coarse, but well intended. A lad chalking on a wall, the suspended figure inscribed “Tom Nero,” prepares us for the future fate of this young tyrant, and shows by anticipation the reward of cruelty (134).

The First Stage of Cruelty: Hangman

One boy prophetically writes Nero's name under the picture of a hangman. In the fourth plate, we see this fate realized as Tom appears on the anatomists’ table with the noose still around his neck.

The First Stage of Cruelty: Hangman

Shesgreen

To the left of this group a boy sketches a prophetic stick drawing of “Tom Nero” hanging from a gallows (77).

The First Stage of Cruelty: Hangman

Uglow

a boy foretells Tom Nero’s fate by drawing a gibbet on the wall (56).

The First Stage of Cruelty: Sword

Shesgreen

a boy aims a stick at an unsuspecting cock held in position by another youth (77).