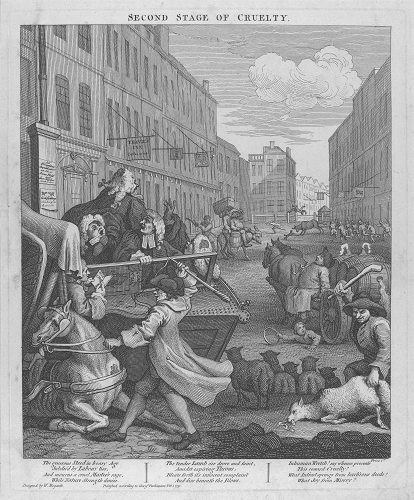

The Second Stage of Cruelty

1750/1

13 13/16” X 11 3/4” (H X W)

View the full resolution plate here.

Tom has progressed from dogs to horses, and the children of the first plate could very well have grown into the adults of the second. Here, an older Tom beats his own horse while a man takes down his name, presumably to report his cruelty (analogous to the do-gooder of the initial plate. The chaos of the scene is intensifying--a loose bull in the very background of the plate attacks and is pursued. A man spears a donkey. A small child is crushed by the wheels of a cart. A man in the foreground beats his sheep to death. Again, although this is Tom's story, there is the sense that he is but one participant in a larger, largely unpunished scene. Indeed, many commentators have argued that the source of Tom’s frustration with his animal is the greed of the magistrates who greedily pile aboard his carriage to save money on a fare, causing the horse to collapse from the additional weight. Thus, the “powers that be” not only fail to prevent the increasing chaos, they also contribute to it.

The Second Stage of Cruelty

Paulson, Ronald. Hogarth’s Graphic Works. (1965)

CAPTION:

The generous Steed in hoary Age

Subdu'd by Labour lies;

And mourns a cruel Master's rage,

While Nature Strength denies.

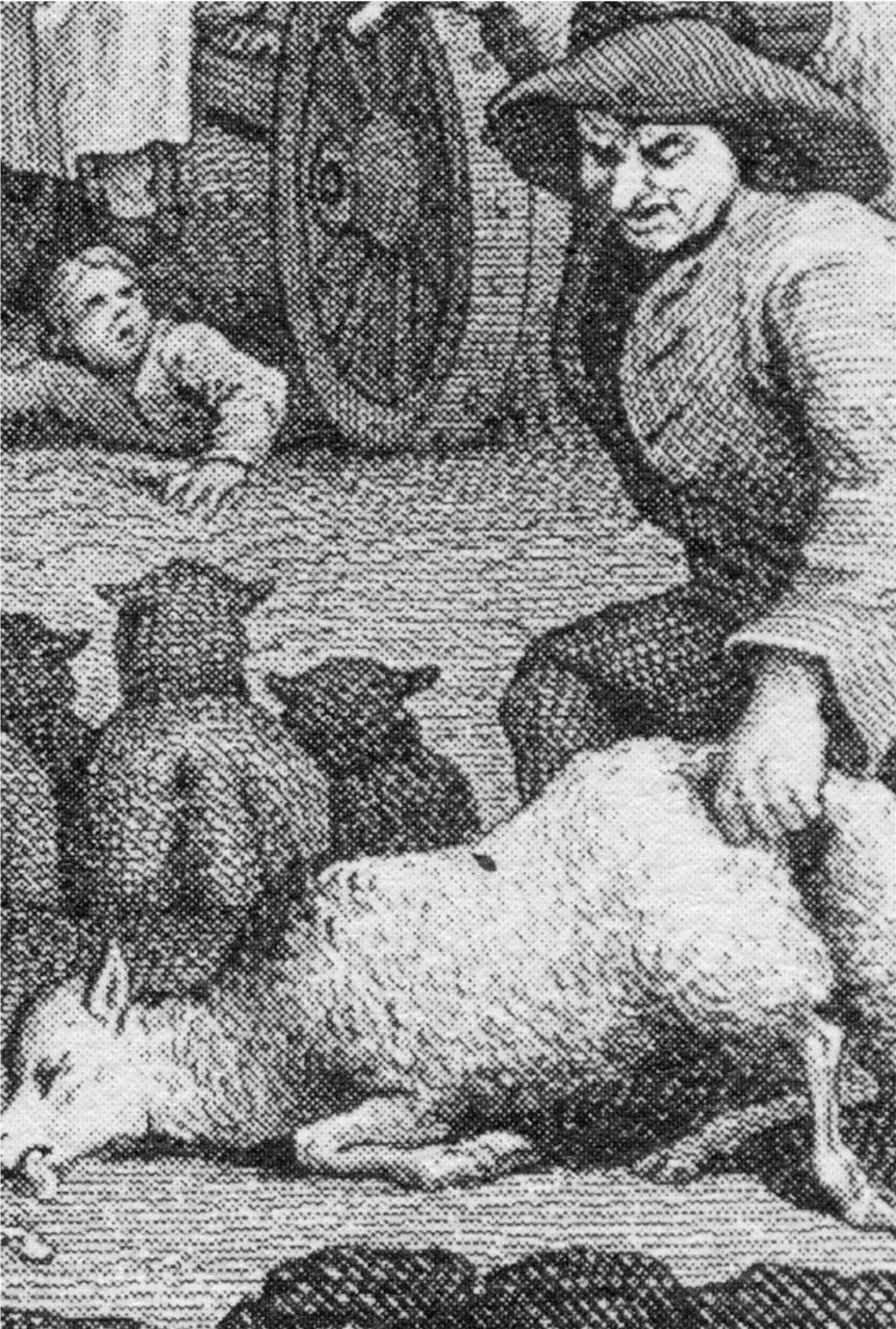

The tender Lamb o'er drove and faint,

Bleats forth it's innocent complaint

Amidst expiring Throws;

And dies beneath the Blows.

Inhuman Wretch! say whence proceeds

This coward Cruelty?

What Int'rest springs from barb'rous deeds?

What Joy from Misery?

In this print unconscious cruelty is added to conscious. Nero's sadistic cruelty, beating the disabled horse, points up the less apparent cruelty in the sleeping drayman running over a boy and in the barristers whose weight has caused the collapse of the horse Nero beats. Both carriage and horse have collapsed because the barristers have crowded in to save coach-fare. The "THAVIES INN Coffee house" tells us where they are. "Thavies-Inn, another of the Inns of Chancery, which is but small, but chiefly taken up by the Welch Attornies" was the end of the longest possible shilling fare from Westminster, which would be the source or destination of these barristers (see The History and Survey of London ... By a Gentleman of the Inner Temple, 1753, I, 800). The one good man (cf. the young gentleman with his tart in Pl. 1) is taking down information in order to report the cruel hackney coach driver: "N° 24 T. Nero" (on the door is a plaque marked "GR N° 24").

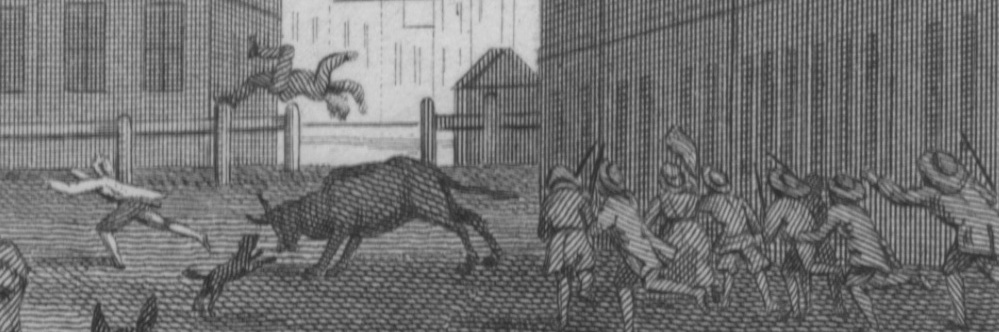

The activity in the far distance is explained by a typical handbill of bull-baiting:

This is to give notice to all gentlemen, gamesters, and others, that on this present Monday is a match to be fought by two dogs, one from Newgate market, against one from Hony-lane market, at a bull, for a guinea to be spent; five let-goes out off hand, which goes fairest and farthest in wins all; likewise a green bull to be baited, which was never baited before; and a bull to be turned loose with fireworks all over him; also a mad ass to be baited, with variety of bull-baiting and bear-baiting, and a dog to be drawn up with fireworks [quoted, Besant, p. 440].

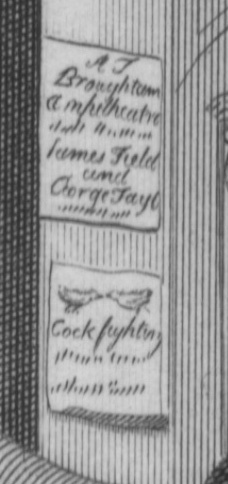

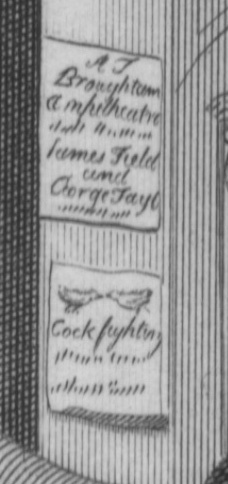

The signs along the wall refer to other cruel sports: "At Broughtons Amphitheater . . . lames Field and Geo: Taylor. . . ." Jack Broughton (1705-89), the "father" of pugilism, had built his amphitheater in Hanway Street, Oxford Street, in 1742. His famous fight with Slack was still in the public mind. This had taken place April 11, 1750, with the Duke of Cumberland backing his protégé Broughton for £1o,ooo. A blow between the eyes blinded Broughton and won Slack the fight: the Duke never forgave Broughton, whose career was finished (see The Bruiser Bruis'd, BM Sat. 3077). George Taylor died on February 21, 1750; he had risen quickly as a fighter but made the mistake of challenging Broughton, who was at the top of his form while Taylor was still under twenty, and he was soundly beaten. Hogarth celebrated his death in a drawing, supposedly designed for his tombstone (but not used): "George Taylor the Pugilist, wrestling with Death" (Oppé, pls. 75, 76, cat. nos. 79 a and b; BM Sat. 3072; see also Caulfield, 4, 207-08). Whether Taylor ever fought James Field I do not know, but both were recently dead. For Field, see The Reward of Cruelty.

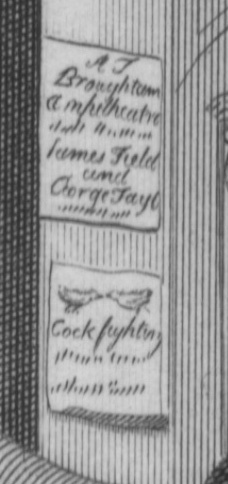

The other sign refers to "Cock fighting," and beyond Thavies' Inn's sign are the signs of a rummer and of crossed keys (212-213).

The Second Stage of Cruelty

Shesgreen, Sean. Engravings by Hogarth. (1973)

Having become a hackney coach driver, Tom, like his peers, transfers the practice of his malicious cruelty to the animal he encounters in his occupation. By permitting too many stingy barristers to ride is coach r a higher fare, he has caused his horse to break its leg, overturning the carriage in front of the “Thavies Inn Coffee house.” As the frightened barristers escape, Tom flogs the animal, senselessly gouging the eye from the crying horse. His name and coach number (“No 24 T. Nero”) are noted by a benevolent man who will report the fellow to his master.

Various other cruel practices occur around Tom: a drover clubs a tardy lamb (symbol of peace and innocence) to death; a driver of a beer cart, asleep and probably drunk, runs over a fallen child; a man rods an overloaded donkey with a pitchfork; and a mob baits a bull. On the wall stand posters of legitimized human cruelty. “At Broughtons Amphitheater . . . James Field and Geo: Taylor . . .” announces a boxing match. A sign below it proclaims “Cockfighting” (78).

The Second Stage of Cruelty

Uglow, Jenny. Hogarth: A Life and a World. (1997)

Cruel boys become vicious men. In the second plate animals are abused at work, not in play. Tom lashes an old nag which has fallen to its knees and overturned the coach; a sheep is being beaten on its way to the slaughter. Bull-baiting is going on in the distance. But there is already a difference: the cruelty applied to animals destroys men. The sleeping carter has driven his heavy load over a boy, and the written signs posted on the wall put “Cockfighting” below an advertisement for Broughton’s Amphitheatre. He rounds at Broughton’s were notoriously rough, and the battles were not all with fists: one contemporary bill advertised that the contestants would fight in the following manner, viz.: to have their left feet strapt down to the stage within reach of the other’s right leg; and the most bleeding wounds to decide the wager.

Hogarth’s poster announces a match between “James Field and Geo: Taylor”. No contemporary viewer could miss the points. James Field had been hanged only two weeks before the prints came out and “George the Barber” Taylor had died in February 1750 (Hogarth produced marvellous drawings of him, wrestling with death). And less than a year later, in April 1750, Broughton himself fought his final match, carrying a bet of £10,000 for “Butcher” Cumberland. He lost to his opponent, Slack, when he was blinded by a blow between the eyes: “The Duke never forgave Broughton, whose career was finished.”

The street where this disturbing scene takes place is Thavies Inn, and the overturned coach is loaded with barristers more concerned at their plight than that of the horse. The gentle boy of the first plate, now a man, is noting down the accident to report the driver. Hogarth suggests that by “reporting” what happens—as he is doing—some good may come. But it will not come to Tom, who is next seen in a rural churchyard being apprehended for the murder of Ann Gill, a maidservant whom he has seduced and persuaded to steal her mistress’ plate (502-504).

The Second Stage of Cruelty

Trusler, Rev. J. and E.F. Roberts. The Complete Works of William Hogarth. (1800)

Tom Nero is now a hackney coachman, and displaying his disposition in his conduct to a horse. Worn out by ill usage, and exhausted by fatigue, the poor animal has fallen down, and overset the carriage, and broken his leg. The scene is laid at Thavies-Inn Gate: four brethren of the brawling bar, who have joined to pay three-pence each for a ride to Westminster Hall, are, in consequence of the accident, overturned, and exhibited at the moment of creeping out of the carriage. These illustrious periwig-pated personages were probably intended as portraits of advocates eminent in their day: their names we are not able to record.

A man taking the number of the coach is marked with traits of benevolence, which separate him from the savage ferocity of Nero, or the terror of these affrighted lawyers.

A further exemplification of extreme barbarity, a drover is beating an expiring lamb with a large club. The wheels of a dray pass over an unfortunate boy, while the drayman, regardless of the consequences, sleeps on the shafts.

In the background is a poor overladen ass: the master, presuming on the strength of this patient and ill-treated animal, has mounted upon his back and taken a loaded porter behind him. An over-driven bull, followed by a crowd of heroic spirits, has tossed a boy. Two bills pasted on the wall advertise cock-fighting and Broughton’s amphitheatre for boxing, as further specimens of national civilisation.

Parts of this print, says Mr. Ireland, may at first sight appear rather overcharged, but some recent examples convince us that they are not so. In the year 1790, a fellow was convicted of lacerating and tearing out the tongue of a horse; but there being no evidence of his bearing any malice toward the proprietor, or doing it with a view of injuring him, this diabolical wretch, not having violated any then existing statute, was discharged without punishment (134).

The Second Stage of Cruelty

Paulson, Ronald. Popular and Polite Art in the Age of Hogarth. (1979)

Looking back, we have to see the first Stage of Cruelty as defined by the St. Giles Parish officers, and the second by the very decided presence of the bulky lawyers who are in fact responsible for the collapsed horse which Nero is beating (they have crowded in to save a fare). Thus we proceed to the grimly threatening constabulary of Cruelty in Perfection and the surgeon-magistrate of The Reward of Cruelty, those representatives of the law, the forces from above from whom Nero—as is finally made explicit in his “reward”—serves merely as someone who is not (to use Fielding’s phrase) “beyond the reach of . . . capital laws” (8).

The Second Stage of Cruelty is based on Miller, no.8:

As Hackney-Coachman, who was just set up, had heard that the Lawyers used to club their Three-Pence a-piece, four of them, to go to Westminster, and then being call’d by a Lawyer at Temple-Bar, who, with two others in the Gowns, got into his Coach, he was bid to drive to Westminster-Hall; but the Coachman still holding his Door open, as if he waited for more Company; one of the Gentlemen asked him, why he did not shut the Door and go on, the Fellow, scratching his Head, cry’d you know, Master, my Fare’s a Shilling, I can’t go for Nine-Pence.

The joke balances the coachman’s wit (or simplicity) against the stingy lawyers; Hogarth’s print, in which the sign “Thavies Inn” indicated the farthest stage from Westminster for a one-shilling fare, exposes the dying horse, who has collapsed under the weight of the barristers and is being beaten to death by the coachman. He has in effect deconstructed Miller’s joke, laying open its repressed center (79).

The Second Stage of Cruelty

Dobson, Austin. William Hogarth. (1907)

The Four Stages of Cruelty are a set of plates exhibiting the “progress” of one Thomas Nero, who, from torturing dogs and horses, advances by rapid stages to seduction and murder, and completes his career on the dissecting table at Surgeon’s Hall. They have all the downright power of Hogarth’s best manner; but they are unrelieved by humour of any kind, and are consequently painful and even repulsive. “The leading points in these as well as the two preceding prints,” says Hogarth, “were made as obvious as possible, in the hope that their tendency might be seen by men of the lowest rank. Neither minute accuracy of design, nor fine engraving was deemed necessary, as the latter would render them too expensive for the persons to whom they were intended to be useful.” These words should be borne in mind in considering them. . . . The price of the ordinary impressions was a shilling the plate, and an unsuccessful attempt was made to sell them even more cheaply by roughly cutting them on a large scale in wood (105-106).

The Second Stage of Cruelty

Quennell, Peter. Hogarth’s Progress. (1955)

The lesson taught by the Four Stages of Cruelty is no less deliberately rammed home. Tom Nero, an undeserving Charity Boy, begins by torturing a stray dog, as the driver of a hackney carriage unmercifully thrashes his broken-down horse, murders a servant-girl whom he has previously seduced and persuaded to steal her master’s silver, and at last appears as a disemboweled corpse, exposed to the scientific brutality of the anatomists at Surgeons’ Hall (210).

The Second Stage of Cruelty: Bull

Paulson, Hogarth's Graphic Works

The activity in the far distance is explained by a typical handbill of bull-baiting:

This is to give notice to all gentlemen, gamesters, and others, that on this present Monday is a match to be fought by two dogs, one from Newgate market, against one from Hony-lane market, at a bull, for a guinea to be spent; five let-goes out off hand, which goes fairest and farthest in wins all; likewise a green bull to be baited, which was never baited before; and a bull to be turned loose with fireworks all over him; also a mad ass to be baited, with variety of bull-baiting and bear-baiting, and a dog to be drawn up with fireworks [quoted, Besant, p. 440] (212).

The Second Stage of Cruelty: Nero

Here, an older Tom beats his own horse while a man takes down his name, presumably to report his cruelty (analogous to the do-gooder of the initial plate.

Again, although this is Tom's story, there is the sense that he is but one participant in a larger, largely unpunished scene. Indeed, many commentators have argued that the source of Tom’s frustration with his animal is the greed of the magistrates who greedily pile aboard his carriage to save money on a fare, causing the horse to collapse from the additional weight. Thus, the “powers that be” not only fail to prevent the increasing chaos, they also contribute to it.

The Second Stage of Cruelty: Nero

Paulson, Hogarth's Graphic Works

Nero's sadistic cruelty, beating the disabled horse, points up the less apparent cruelty in the sleeping drayman running over a boy and in the barristers whose weight has caused the collapse of the horse Nero beats. Both carriage and horse have collapsed because the barristers have crowded in to save coach-fare. The "THAVIES INN Coffee house" tells us where they are. "Thavies-Inn, another of the Inns of Chancery, which is but small, but chiefly taken up by the Welch Attornies" was the end of the longest possible shilling fare from Westminster, which would be the source or destination of these barristers (see The History and Survey of London ... By a Gentleman of the Inner Temple, 1753, I, 800). The one good man (cf. the young gentleman with his tart in Pl. 1) is taking down information in order to report the cruel hackney coach driver: "N° 24 T. Nero" (on the door is a plaque marked "GR N° 24") (212).

The Second Stage of Cruelty: Nero

Shesgreen

Having become a hackney coach driver, Tom, like his peers, transfers the practice of his malicious cruelty to the animal he encounters in his occupation. By permitting too many stingy barristers to ride is coach r a higher fare, he has caused his horse to break its leg, overturning the carriage in front of the “Thavies Inn Coffee house.” As the frightened barristers escape, Tom flogs the animal, senselessly gouging the eye from the crying horse. His name and coach number (“No 24 T. Nero”) are noted by a benevolent man who will report the fellow to his master (78).

The Second Stage of Cruelty: Nero

Uglow

Tom lashes an old nag which has fallen to its knees and overturned the coach. The gentle boy of the first plate, now a man, is noting down the accident to report the driver (502).

Hogarth suggests that by “reporting” what happens—as he is doing—some good may come (504).

The Second Stage of Cruelty: Nero

Trusler

Tom Nero is now a hackney coachman, and displaying his disposition in his conduct to a horse. Worn out by ill usage, and exhausted by fatigue, the poor animal has fallen down, and overset the carriage, and broken his leg. The scene is laid at Thavies-Inn Gate: four brethren of the brawling bar, who have joined to pay three-pence each for a ride to Westminster Hall, are, in consequence of the accident, overturned, and exhibited at the moment of creeping out of the carriage. These illustrious periwig-pated personages were probably intended as portraits of advocates eminent in their day: their names we are not able to record.

A man taking the number of the coach is marked with traits of benevolence, which separate him from the savage ferocity of Nero, or the terror of these affrighted lawyers (134).

The Second Stage of Cruelty: Nero

Paulson, Popular and Polite Art

the very decided presence of the bulky lawyers . . .are in fact responsible for the collapsed horse which Nero is beating (they have crowded in to save a fare) (8).

The Second Stage of Cruelty is based on Miller, no.8:

As Hackney-Coachman, who was just set up, had heard that the Lawyers used to club their Three-Pence a-piece, four of them, to go to Westminster, and then being call’d by a Lawyer at Temple-Bar, who, with two others in the Gowns, got into his Coach, he was bid to drive to Westminster-Hall; but the Coachman still holding his Door open, as if he waited for more Company; one of the Gentlemen asked him, why he did not shut the Door and go on, the Fellow, scratching his Head, cry’d you know, Master, my Fare’s a Shilling, I can’t go for Nine-Pence.

The joke balances the coachman’s wit (or simplicity) against the stingy lawyers; Hogarth’s print, in which the sign “Thavies Inn” indicated the farthest stage from Westminster for a one-shilling fare, exposes the dying horse, who has collapsed under the weight of the barristers and is being beaten to death by the coachman. He has in effect deconstructed Miller’s joke, laying open its repressed center (79).

The Second Stage of Cruelty: Signs

Paulson, Hogarth's Graphic Works

The "THAVIES INN Coffee house" tells us where they are. "Thavies-Inn, another of the Inns of Chancery, which is but small, but chiefly taken up by the Welch Attornies" was the end of the longest possible shilling fare from Westminster, which would be the source or destination of these barristers (see The History and Survey of London ... By a Gentleman of the Inner Temple, 1753, I, 800).

. . . beyond Thavies' Inn's sign are the signs of a rummer and of crossed keys (212-213).

The Second Stage of Cruelty: Signs

Paulson, Popular and Polite Art

Hogarth’s print, in which the sign “Thavies Inn” indicated the farthest stage from Westminster for a one-shilling fare, exposes the dying horse, who has collapsed under the weight of the barristers and is being beaten to death by the coachman (79).

The Second Stage of Cruelty: Wall Sign

A sign advertises a boxing match between James Field and George Taylor and cockfighting; both are forms of "cruelty." Field's skeleton is on display in Plate 4 of this series, demonstrating that human cruelty has but one result.

The Second Stage of Cruelty: Wall Sign

Paulson, Hogarth's Graphic Works

The signs along the wall refer to other cruel sports: "At Broughtons Amphitheater . . . lames Field and Geo: Taylor. . . ." Jack Broughton (1705-89), the "father" of pugilism, had built his amphitheater in Hanway Street, Oxford Street, in 1742. His famous fight with Slack was still in the public mind. This had taken place April 11, 1750, with the Duke of Cumberland backing his protégé Broughton for £1o,ooo. A blow between the eyes blinded Broughton and won Slack the fight: the Duke never forgave Broughton, whose career was finished (see The Bruiser Bruis'd, BM Sat. 3077). George Taylor died on February 21, 1750; he had risen quickly as a fighter but made the mistake of challenging Broughton, who was at the top of his form while Taylor was still under twenty, and he was soundly beaten. Hogarth celebrated his death in a drawing, supposedly designed for his tombstone (but not used): "George Taylor the Pugilist, wrestling with Death" (Oppé, pls. 75, 76, cat. nos. 79 a and b; BM Sat. 3072; see also Caulfield, 4, 207-08). Whether Taylor ever fought James Field I do not know, but both were recently dead. For Field, see The Reward of Cruelty. The other sign refers to "Cock fighting," and beyond Thavies' Inn's sign are the signs of a rummer and of crossed keys (212-213).

The Second Stage of Cruelty: Wall Sign

Uglow

written signs posted on the wall put “Cockfighting” below an advertisement for Broughton’s Amphitheatre. He rounds at Broughton’s were notoriously rough, and the battles were not all with fists: one contemporary bill advertised that the contestants would fight in the following manner, viz.: to have their left feet strapt down to the stage within reach of the other’s right leg; and the most bleeding wounds to decide the wager. Hogarth’s poster announces a match between “James Field and Geo: Taylor”. No contemporary viewer could miss the points. James Field had been hanged only two weeks before the prints came out and “George the Barber” Taylor had died in February 1750 (Hogarth produced marvellous drawings of him, wrestling with death). And less than a year later, in April 1750, Broughton himself fought his final match, carrying a bet of £10,000 for “Butcher” Cumberland. He lost to his opponent, Slack, when he was blinded by a blow between the eyes: “The Duke never forgave Broughton, whose career was finished.” (502-504).