The Reward of Cruelty

1750/1

14” X 11 3/4" (H X W)

View the full resolution plate here.

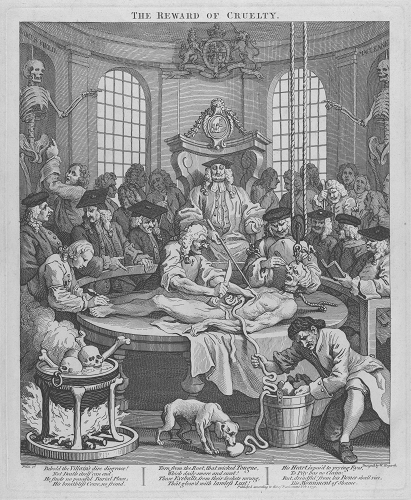

Although plate 3 is horrific in its graphic depiction of a brutal murder, it is not the most grotesque plate in the series. That honor is held by the concluding plate, "The Reward of Cruelty " and the dissection of Tom's body. .In the ultimate irony, the heartless Tom Nero becomes a victim of sorts as he is brutalized on the anatomists’ table in an act that exceeds even his most scandalous crime. Commentators, noting the title's judgmental ring, have discussed the suitability of the punishment for one who has inflicted such tortures on others. Uglow comments, "This is a moral as well as physical dissection. Tom's cursing tongue has been torn out by its roots; his lusting eyes gouged out; his loveless heart thrown to a mangy dog. Skulls and bones boil over a fire, like a cannibal rite, a visceral pagan sacrifice" (505). While Shesgreen, too, notes that the "smiling dog takes his revenge on Tom's cruelty to animals by eating his heart," he also explains that the implications of cannibalism are even stronger in earlier versions of the plate, and further points out the "satire on surgeons...sadistic doctors, oblivious to the grotesqueness of their autopsy delightfully carving up the corpse of Nero" (80). This is institutionalized cruelty in the name of science—state sanctioned and mainstreamed Importantly, Paulson recognizes that the "assembled surgeons...are enjoying their work as much as Nero enjoyed his in the first plate" (Graphic 215). further underscoring the fact that Nero and his companions are merely furthering a cycle of cruelty that extends from the streets to the more learned members of society, among figures who should serve as benefactors, even healers, to us all.

Moreover, Tom's autopsy would have had special significance for Hogarth's lower-class audience. Paulson notes that they would recognize the "taboos surrounding human dissection. The popular beliefs that reverberate in the plate include the possibility of resuscitation after hanging, the magically therapeutic powers of a malefactor's corpse and the ability of the spirit of the dead to return to the living" (Popular 7). He reminds us that "the notorious Tyburn riots of the years leading up to 1752...were aimed at rescuing the victim's body from dissectors...a kind of class solidarity" (Popular 7). Fiona Haslam comments that “execution, mutilation and dismemberment were terrifying to all believers in the resurrection of the body. Dismemberment was thought to deny the possibility of the resurrection at the Day of Judgment” (263). Uglow adds that "Hogarth's 'ordinary' viewers might well have been on Tom's side," and concludes that here," Hogarth himself is an anatomist, performing an autopsy on a diseased society, a sharp-eyed dissection" (506) John Trusler notes that Hogarth insisted the price of the series remain low so that many of the poor could afford it (135).

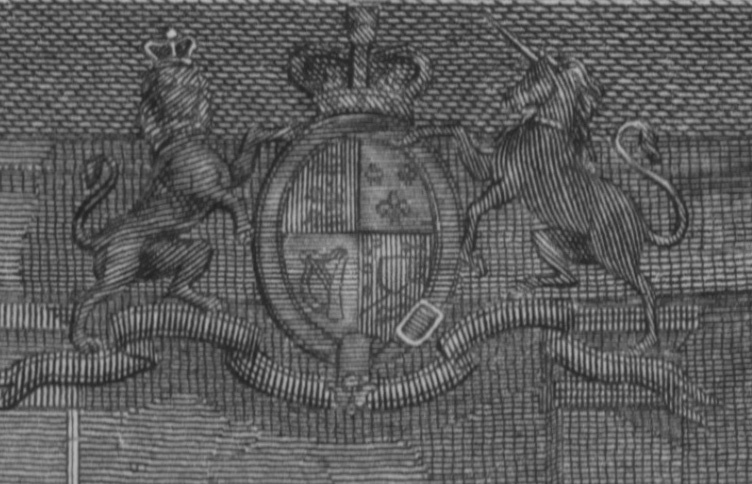

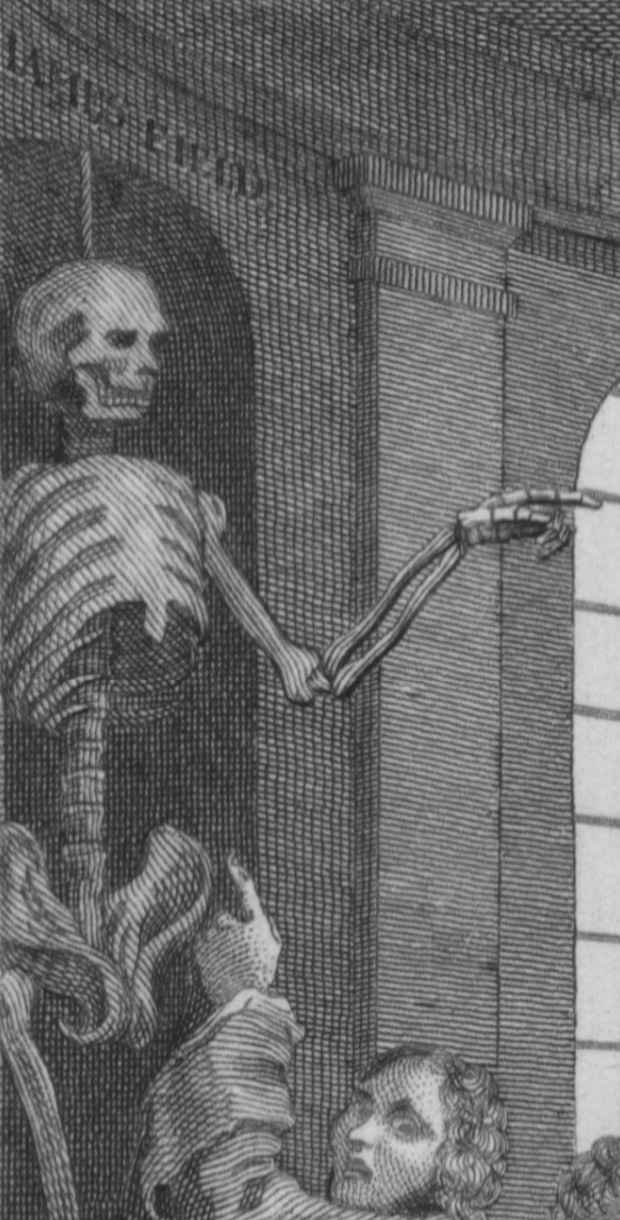

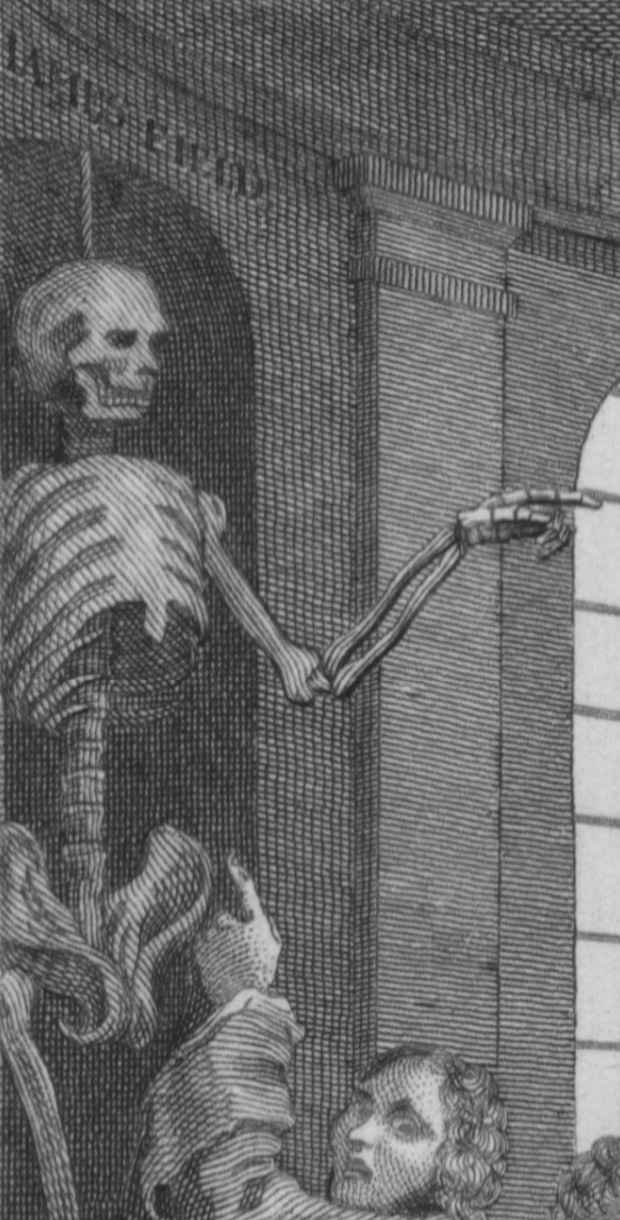

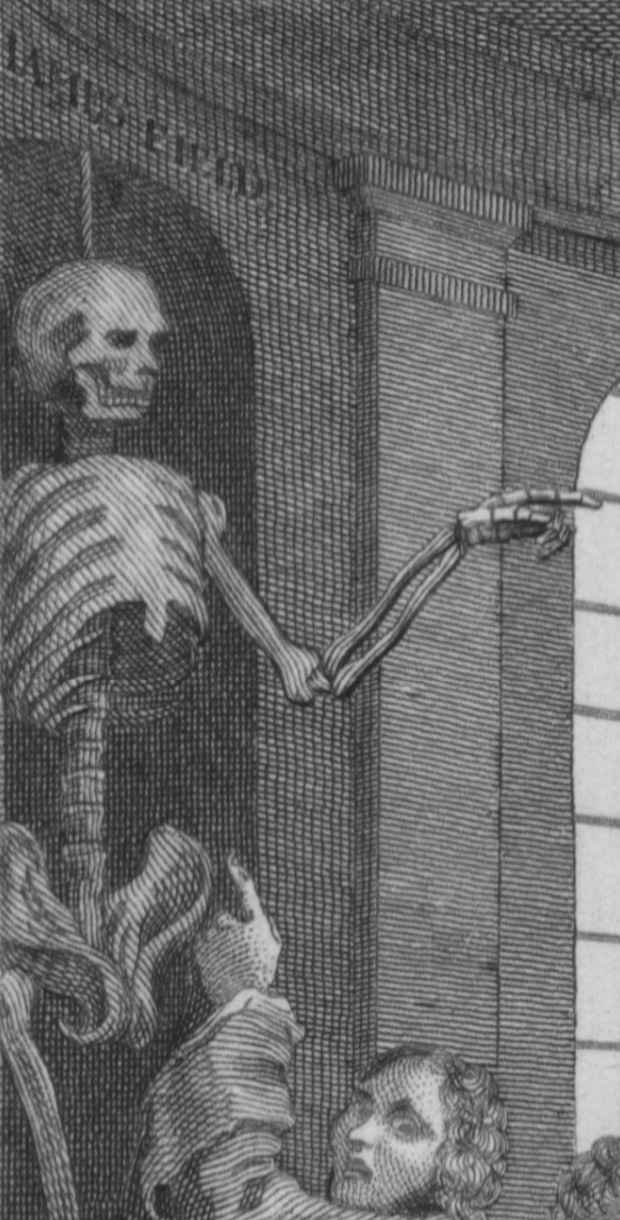

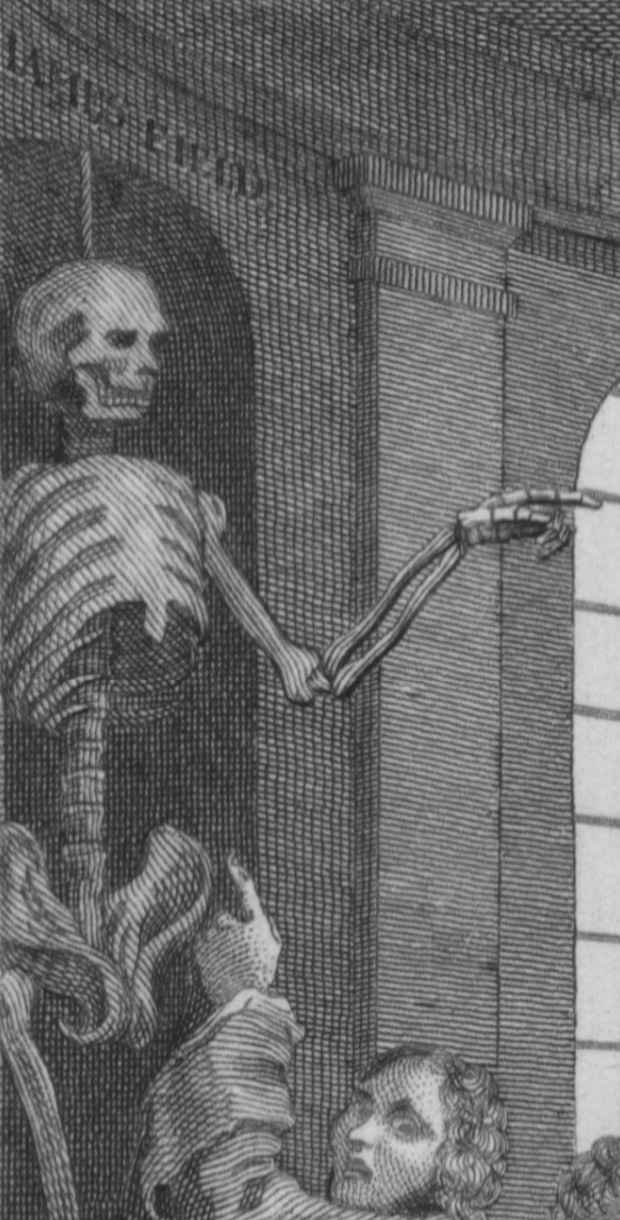

While the scene itself is frightening, even more repulsive is the lack of visible emotion in the plate. The setting is Surgeon’s Hall; the President’s chair bears the symbol of the Royal College of Physicians—highlighted by a pointing skeleton on either side of the room. Many commentators have observed the detachment of the onlookers: Peter Quennell cites the “cold scientific brutality of the anatomists” (210), while Haslam notes their “insensitivity and callousness” (263). More appalling that the apathy of the spectators is the smug satisfaction of the man presiding over the event. Dressed as a magistrate and often identified as St. Bartholomew’s physician John Freke, he sits in absolute judgment over the scene, pointing to the now-empty chest cavity where Tom Nero’s cruel heart once resided. One might note the seemingly appropriate Old Testament justice being administered to a man who dismembered a pregnant woman and who tormented dogs and horses with instruments not unlike what are being employed against him here.

Tom's death, however, becomes, less of a fitting punishment and more the scene of excessive display, revealing a society which punishes cruelty with vulgarity and delights in the power to do so. The tract to which Ann Gill's mutilated hand points in the third plate ultimately reveals a deeper meaning for the series—one that is distinctly opposed to capital punishment by marking the territory as "God's Revenge." By usurping that power, the dissectors of the final plate commit the most serious cruelties of all. Entering a realm not meant for humans, the physician acts a final judge, and if the common fear of the inability of the deceased body to be redeemed us a reality, the physician not only has dominion over the body but over the soul as well, usurping God’s power to determine the eternal fate of the criminal.

Having dispensed with his immortal soul, the anatomist also achieves the dehumanization of the body. Hogarth likens the dissection to the brutality of the cockfight by having the circular form of the central table here achieve a striking similarity, as Derek Jarrett and others have noted, to the cockpit. Jarrett states that Hogarth was critical of this form of activity, as it combined “a love of cruelty and the love of gambling, which, in his opinion, degraded the Englishman’s pleasures into vices” (England 175). Further, he notes the resemblance of the anatomy lecturer to the blind nobleman who is the central figure of a later Hogarth plate “Pit Ticket: The Cockpit” (England 176) Shesgreen further strengthens Biblical implications by stating that this work “reflects Leonardo’s Last Supper” (80). As these men make bets and delight in the cocks’ brutality, which often resulted in the dismemberment of one or both of the birds, the doctors in the dissection scene escalate this cruelty by substituting the dismemberment of a man by fellow men as their chosen form of entertainment. Hogarth makes a similar comment on a doctor’s ability to animalize his patients in a scene from The Four Times of the Day called “Night.” There, a drunken barber-surgeon illegally bleeds his victim while holding his nose in a position that causes him to resemble a pig. Thus, Hogarth warns his public that medical professionals often do not regard patients as fully human and their ability to butcher them without remorse, even with delight, stems from this perception.

Uglow states that Nero's pointing finger "implicates both the people and the 'constitution' that governs them. Crime, disorder and impulse find their mirror image in punishment and law" (506). This condemnation serves to make the series less a simple drama of "Virtue" and "Vice" and more an unraveling of the complexity of individual action in a society which only serves to perfect the cruelties that it punishes as unlawful.

The Reward of Cruelty

Shesgreen, Sean. Engravings by Hogarth. (1973)

Designed both as a fitting end to Tom Nero’s life and as a satire on surgeons, the final scene shows a number of sadistic doctors, oblivious to the grotesqueness of their autopsy, delightedly carving up the corpse of Nero, who appears to suffer at their knives. With a large pulley screw in his head and the hangman’s rope around his neck, Tom’s body (the initials “T N” appear on his arm) is the subject of an anatomy lesson. One surgeon gouges out his eye in much the same way as the boy in Plate I scoops out the bird’s eye; a second murderous-looking fellow pulls out his entrails, which a casual assistant puts in a tub; a third carves open his foot. The victim’s finger points admonishingly to the boiling pot of skulls and bones which rests on a stand of human femurs. Next to the pot a smiling dog takes his revenge on Tom’s cruelty to animals by eating his heart.

The anatomy lesson is narrative programmatically by an impassive figure. Above his head the emblem of the Royal College of Physicians depicting a doctor’s hand taking a pulse stands in contrast to the grotesque scene below. Above that hangs the royal arms.

The Reward of Cruelty

Paulson, Ronald. Hogarth’s Graphic Works. (1965)

CAPTION:

Behold the Villain's dire disgrace!

Not Death itself can end.

He finds no peaceful Burial-Place;

His breathless Corse, no friend.

Torn from the Root, that wicked Tongue,

Which daily swore and curst!

Those Eyeballs, from their Sockets wrung,

That glow'd with lawless Lust!

His Heart, expos’d to prying Eyes,

To Pity has no Claim:

But, dreadful! From his Bones shall rise,

His Monument of Shame.

The last line means that his skeleton will join those of "JAMES FIELD" and "MACLEANE" on display. Field was a pugilist (referred to in PI. 2), hanged February 11, 1751, shortly before Hogarth's prints appeared (February 23). His name must have replaced "GENTL HARRY" as a last-minute change to catch the popular reaction and, tied in with the second plate, to offer another example of cruelty rewarded. Macleane was a highwayman who had been hanged at Tyburn the previous October 3 (1750). He was called "The Gentleman Highwayman," and was said to be son of an Irish Dean and brother of a Calvinist minister at The Hague; he lived in St. James' Street, across from White's and just down the way from the palace. In 1749 he had robbed Horace Walpole and almost—apparently by accident—killed him (London Magazine, 18, 1749, 526; Gentleman's Magazine, 19, 1749, 522). He was handsome, had taken to the road after losing his wife and failing in business, and was much admired by the ladies, being visited by 3,000 people in his cell the day before his execution (see Caulfield, 4, 87-96). Both of these rogues were more timely than the "GENTN HARRY" of the first state: Henry Simms, known as "Young Gentleman Harry," was a robber who was hanged June 17, 1747 (see London Magazine, 16, 1747, 146 and 291. For Field's execution, see Gentleman's Magazine, 21,1751,91).

The scene of the print is a composite. The Surgeons had separated from the Barbers in 1745 and were no longer allowed to use the dissecting theater of the Barber-Surgeons' Company, Monkwell Street; and their new theater, close to Newgate Gaol, was not opened until August 1751. W. Brockbank and J. Dobson have shown that Hogarth's interior resembles the Cutlerian theater of the Royal College of Physicians Surgeons' Company, and the dissections were advertised so that the public might come to ponder the wages of sin. Nero's corpse, with the rope still around his neck, has accordingly been delivered for dissection. His initials "T N" are burnt on his arm. The assembled surgeons, wearing birettas and mortar boards, are enjoying their work as much as Nero enjoyed his in the first plate. The complete reversal, in which Nero has become himself the victim, is emphasized by the dog (cf. Pl. 1) who is present, licking his heart. J. Ireland (2, 72 n.) believed that the president resembled Hogarth's friend, John Freke (1688-1756), surgeon at St. Bartholomew's Hospital from 1729 to 1755.

Antal (p. 166) sees the print as derived from one of Egbert van Heemskerk's animal-headed prints, A Satire on Quacks and Quackery, showing the animals in a dissection hall (c. 1730, engraved by Toms; BM Sat. 1861); Mitchell (p. xxvii) connects it with a print by A. J. Stock (see R. N. Wegner, Das Anatomenbildnis, 1939, p. 65); and another possibility is Leonard Gaultier's title page for André du Laurens' Opera omnia (1628) (214-215).

The Reward of Cruelty

Uglow, Jenny. Hogarth: A Life and a World. (1997)

Tom’s end has come. In the ghastly final print he has been hanged, cut down and brought to the Surgeons’ Hall. The male body replaces the prone, murdered female. With horrific vitality Hogarth makes Tom’s corpse look alive, as if jerking up in pain as the surgeons probe his eye-sockets and excavate the delicate sinews of his ankles. The bespectacled knife-wielder in the centre (said to be based on John Freke) almost seems to peer at Tom’s reaction while he reaches into his hollow ribcage, directed by the magisterial President with his stick. Below his blade intestines sneak out towards a vat that already holds another man’s head. This is a moral as well as physical dissection. Tom’s cursing tongue has been torn out by its roots; his lusting eyes gouged out; his loveless heart thrown to a mangy dog. Skulls and bones boil over a fire, like a cannibal rite, a visceral pagan sacrifice.

Aiming at the poor, Hogarth played on their fears of hanging and dissection: but with his characteristics, unnerving, doubleness he also invited their outrage. He condemned Tom Nero outright, but as with Tom Idle, he also allowed people to feel from him at the last. Given the riots of Tyburn when relatives attempted to rescue felons’ bodies from the anatomists, Hogarth’s “ordinary” viewers might well have been on Tom’s sign. And such sympathy would be heightened by the way this final print brought in recent criminal lives, placing the whole scene beneath the pointing skeletons of the recently executed boxer James Field and the highwayman James Maclain (or Maclean), hanged in October 1750.

Maclain, to whom the good man—our “gentler boy”—points in dismayed warning, was the son of a Presbyterian minister. He was a handsome, well-bred rascal, a living Macheath; on the Sunday after he was sentenced, three thousand people crowded to see him and he fainted twice from the heat of his packed cell. His was the pistol that had exploded in Horace Walpole’s face in December 1749, blackening it with powder and shot-marks, and Walpole (who was praised in a Grub Street ballad for not demanding his death) followed his story with interest: “You can’t conceive the ridiculous rage there is of going to Newgate,” he wrote, “and the prints that are published of malefactors, and the memoirs of their lives and deaths set forth with as much parade as—as Marshal Turenne’s—we have no generals worth making a parallel!” Five separate memoirs of Maclain were circulating round London when Hogarth’s prints came out. While keeping a scrupulous moral tone, he need only name him to suggest a parallel between Tom Nero and this hero of the road.

This might be the “effects” of cruelty; the end of a cruel life. But the horror comes both from the corpse and from the way we are implicated, as spectators, with the doctors and polite visitors. Some read; some dispute. All show a pitiless indifference. Hogarth brought the whole of medicine into his ambit: the niches belongs to the old Barber-Surgeon’s Hall, unused since 1745, while the hall itself resembles the theatre of the Royal College of Physicians near Newgate and the President’s chair bears their arms. Many commentators notes the similarity between the curved amphitheatre of a cockpit and the Surgeon’s Hall. The whole scene indicts self-interested, legalized cruelty.

Yet it can be read still another way. The viewpoint is absolutely central, on a level with the corpse’s rigid, pointing finger, forcing us to confront the worse. The shock is intensified—as with Gin Lane—by a kind of relish on Hogarth’s part. The emotion is more complex than outrage: he thrills to the knife, the entrails, the cut flesh. There is pleasure here, in the artist’s power to convey agony. Hogarth himself is an anatomist, performing an autopsy on a diseased society, a sharp-eyed dissection.

Hogarth’s metaphorical use of the body resembles the language of Fielding’s tracts. In the Enquiry, published a month after these prints. Fielding defined the constitution as including the laws and executive provisions but also the Customs, Manners and Habits of the People. These, joined together, do, I apprehend, form the Political, as the several members of the Body, and animal Œconomy, with the Humours, and Habit, compose that which is called the Natural Constitution.

Similar rhetoric lay behind a political print by George Bickham junior, two years before, showing Pelham and Newcastle standing over Britannia on the rack; they too peer at her entrails while her intestines slide down to the floor. In “The Reward of Cruelty” Hogarth’s vision of the bodily punishments inflicted by, and upon, Tom Nero implicated both the people and the “constitution” that governs them. Crime, disorder and impulse fin their mirror image in punishment and law; together they tear at the collective body of the nation, leaving it in a nightmarish, dismembered state (504-506).

The Reward of Cruelty

Paulson, Ronald. Popular and Polite Art in the Age of Hogarth. (1979)

The Reward of Cruelty, by all odds Hogarth’s most horrifying image, is an example of the way in which this second audience [the poor] would have understood what the first [their betters] would probably have only dimly sensed: I refer to the taboos surrounding human dissection. The popular beliefs that reverberate in this plate include the possibility of resuscitation after hanging, the magically therapeutic powers of a malefactor’s corpse, and the ability of the spirit of the dead to return to the living. The notorious Tyburn riots of the years leading up to 1752, as Peter Linebaugh has shown, were essentially aimed at rescuing the victim’s body from the dissectors—a concerted extralegal action by small groups of his friends, relatives or fellow apprentices. These represent a kind of class solidarity, a set of beliefs, unwritten and of the subculture but as reasonable as those with which we are more familiar, namely the views of the “better sort” of people who thought in terms of the legal system and believed in the medical utility and the penal retribution involved in the dissection of malefactors.

Hogarth makes his statement this time by portraying the surgeon in the pose of a magistrate in relation to the condemned malefactor. The Company of Surgeons has made off with Tom Nero’s body from the gallows. Only a year later, in March 1752, did the law equitably settle the matter by making dissection a part of the official penalty the judge could impose upon certain, but not all, criminals. This law, the “Murder Act,” was framed as immediate response to the Penlez riots of 1749 (in which Fielding as Bow Street magistrate played an adversary role). It is not without significance that the dissector in Hogarth’s picture has been traditionally identified as Dr. John Freke, the surgeon who was prevented from dissecting Penlez’s body in the cause célèbre that followed his execution—and who dissect many other criminals. Looking back, we have to see the first Stage of Cruelty as defined by the St. Giles Parish officers, and the second by the very decided presence of the bulky lawyers who are in fact responsible for the collapsed horse which Nero is beating (they have crowded in to save a fare). Thus we proceed to the grimly threatening constabulary of Cruelty in Perfection and the surgeon-magistrate of The Reward of Cruelty, those representatives of the law, the forces from above from whom Nero—as is finally made explicit in his “reward”—serves merely as someone who is not (to use Fielding’s phrase) “beyond the reach of . . . capital laws” (7-8).

The Reward of Cruelty

Trusler, Rev. J. and E.F. Roberts. The Complete Works of William Hogarth. (1800)

The savage and diabolical progress of cruelty is now ended, and the thread of life severed by the sword of justice. From the plate of execution the murderer is brought to Surgeons’-hall, and now represented under the knife of a dissector. This venerable person, as well as his coadjutor who scoops out the criminal’s eye, and a young student scarifying the leg, seem to have just as much feeling as the subject now under their inspection. A frequent contemplation of sanguinary scenes hardens the heart, deadens sensibility, and destroys every tender sensation.

Hogarth was most peculiarly accurate in those little marking which identify. The gunpowder initials “T.N.” on the arm, denote this to be the body of Thomas Nero. The face being impressed with horror has been objected to. It must be acknowledged that this is rather o’erstepping the modesty of nature; but he so rarely deviates from her laws, that a little poetical license may be forgiven, where it produces humour or heightens character.

The skeletons on each side of the print, are inscribed “James Field” (an eminent pugilist), and “Maclean” (a notorious robber). Both of these worthies died by the rope. They are pointing to the physician’s crest, which is carved in the upper part of the president’s chair—viz., a hand feeling a pulse; taking a guinea would have been more appropriate to the practice. The heads of those two heroes of the halter are turned so as to seem ridiculing the president, “scoffing his state, and grinning at his pomp.” Every countenance in this grisly band is marked with that medical importance which dignifies the professors. Some of them we discover to be “from Caledonia’s bleak and barren clime.”

A fellow depositing the intestines in a pail, and a dog licking the murderer’s heart, are disgusting and nauseous objects. The vessel where the skulls and bones bubble-bubble, gives some idea of the infernal cauldron of Hecate (135).

The Reward of Cruelty

Quennell, Peter. Hogarth’s Progress. (1955)

From Oxford itself, on July 29th 1730, the Daily Journal reports a pitched battle fought over the body of William Fuller, purchased as material for dissection, between gownsmen, mob and proctors, which concluded with the buffeted corpse being carried off to Christ Church—an episode that recalls the final scene of Hogarth’s Four Stages of Cruelty (81).

The lesson taught by the Four Stages of Cruelty is no less deliberately rammed home. Tom Nero, an undeserving Charity Boy, begins by torturing a stray dog, as the driver of a hackney carriage unmercifully thrashes his broken-down horse, murders a servant-girl whom he has previously seduced and persuaded to steal her master’s silver, and at last appears as a disemboweled corpse, exposed to the scientific brutality of the anatomists at Surgeons’ Hall (210)

The Reward of Cruelty

Dobson, Austin. William Hogarth. (1907)

The Four Stages of Cruelty are a set of plates exhibiting the “progress” of one Thomas Nero, who, from torturing dogs and horses, advances by rapid stages to seduction and murder, and completes his career on the dissecting table at Surgeon’s Hall. (This dreadful detail was no exaggeration. In vol ii. Of his “Reminiscences,” 1830, p.252, Henry Angelo says that, after seeing the Rev. James Hackman hanged at Tyburn for the murder of Martha Ray—whom, by the way, Hogarth painted—he went the next day to Surgeons’ Hall, where the body is dissected). They have all the downright power of Hogarth’s best manner; but they are unrelieved by humour of any kind, and are consequently painful and even repulsive. “The leading points in these as well as the two preceding prints,” says Hogarth, “were made as obvious as possible, in the hope that their tendency might be seen by men of the lowest rank. Neither minute accuracy of design, nor fine engraving was deemed necessary, as the latter would render them too expensive for the persons to whom they were intended to be useful.” These words should be borne in mind in considering them. . . . The price of the ordinary impressions was a shilling the plate, and an unsuccessful attempt was made to sell them even more cheaply by roughly cutting them on a large scale in wood (105-106).

The Reward of Cruelty: Dog

A dog eats Nero’s heart. This is certainly justice for Tom’s treatment of the dog in the initial plate.

The Reward of Cruelty: Dog

Trusler

A fellow depositing the intestines in a pail, and a dog licking the murderer’s heart, are disgusting and nauseous objects (135).

The Reward of Cruelty: Field

The setting is Surgeons’ Hall; the President’s chair bears the symbol of the Royal College of Physicians—highlighted by a pointing skeleton on either side of the room. This one is identified as James Field.

The Reward of Cruelty: Field

Shesgreen

One figure looks at Tom’s corpse and points to the grinning skeletons of “James Field,” a famous boxer, as if to suggest that Nero’s skeleton will replace Field’s (80).

The Reward of Cruelty: Field

Paulson, Hogarth's Graphic Works

[Nero’s] skeleton will join those of "JAMES FIELD" and "MACLEANE" on display. Field was a pugilist (referred to in PI. 2), hanged February 11, 1751, shortly before Hogarth's prints appeared (February 23). His name must have replaced "GENTL HARRY" as a last-minute change to catch the popular reaction and, tied in with the second plate, to offer another example of cruelty rewarded (214).

The Reward of Cruelty: Field

Trusler

The skeletons on each side of the print, are inscribed “James Field” (an eminent pugilist), and “Maclean” (a notorious robber). Both of these worthies died by the rope. They are pointing to the physician’s crest, which is carved in the upper part of the president’s chair—viz., a hand feeling a pulse; taking a guinea would have been more appropriate to the practice. The heads of those two heroes of the halter are turned so as to seem ridiculing the president, “scoffing his state, and grinning at his pomp.” Every countenance in this grisly band is marked with that medical importance which dignifies the professors. Some of them we discover to be “from Caledonia’s bleak and barren clime” (135).

The Reward of Cruelty: Macleane

The setting is Surgeons’ Hall; the President’s chair bears the symbol of the Royal College of Physicians—highlighted by a pointing skeleton on either side of the room. Macleane was a famous highwayman, a sort of celebrity who had popular appeal.

The Reward of Cruelty: Macleane

Paulson, Hogarth's Graphic Works

[Nero’s] skeleton will join those of "JAMES FIELD" and "MACLEANE" on display.. . . Macleane was a highwayman who had been hanged at Tyburn the previous October 3 (1750). He was called "The Gentleman Highwayman," and was said to be son of an Irish Dean and brother of a Calvinist minister at The Hague; he lived in St. James' Street, across from White's and just down the way from the palace. In 1749 he had robbed Horace Walpole and almost—apparently by accident—killed him (London Magazine, 18, 1749, 526; Gentleman's Magazine, 19, 1749, 522). He was handsome, had taken to the road after losing his wife and failing in business, and was much admired by the ladies, being visited by 3,000 people in his cell the day before his execution (see Caulfield, 4, 87-96) (214).

The Reward of Cruelty: Macleane

Uglow

Maclain, to whom the good man—our “gentler boy”—points in dismayed warning, was the son of a Presbyterian minister. He was a handsome, well-bred rascal, a living Macheath; on the Sunday after he was sentenced, three thousand people crowded to see him and he fainted twice from the heat of his packed cell. His was the pistol that had exploded in Horace Walpole’s face in December 1749, blackening it with powder and shot-marks, and Walpole (who was praised in a Grub Street ballad for not demanding his death) followed his story with interest: “You can’t conceive the ridiculous rage there is of going to Newgate,” he wrote, “and the prints that are published of malefactors, and the memoirs of their lives and deaths set forth with as much parade as—as Marshal Turenne’s—we have no generals worth making a parallel!” Five separate memoirs of Maclain were circulating round London when Hogarth’s prints came out. While keeping a scrupulous moral tone, he need only name him to suggest a parallel between Tom Nero and this hero of the road (505).

The Reward of Cruelty: Macleane

Trusler

The skeletons on each side of the print, are inscribed “James Field” (an eminent pugilist), and “Maclean” (a notorious robber). Both of these worthies died by the rope. They are pointing to the physician’s crest, which is carved in the upper part of the president’s chair—viz., a hand feeling a pulse; taking a guinea would have been more appropriate to the practice. The heads of those two heroes of the halter are turned so as to seem ridiculing the president, “scoffing his state, and grinning at his pomp.” Every countenance in this grisly band is marked with that medical importance which dignifies the professors. Some of them we discover to be “from Caledonia’s bleak and barren clime” (135).

The Reward of Cruelty: Nero

The heartless Tom Nero becomes a victim of sorts as he is brutalized on the anatomists’ table in an act that exceeds even his most scandalous crime.

Uglow states that Nero's pointing finger "implicates both the people and the 'constitution' that governs them (506).

The Reward of Cruelty: Nero

Shesgreen

Designed both as a fitting end to Tom Nero’s life and as a satire on surgeons, the final scene shows a number of sadistic doctors, oblivious to the grotesqueness of their autopsy, delightedly carving up the corpse of Nero, who appears to suffer at their knives. With a large pulley screw in his head and the hangman’s rope around his neck, Tom’s body (the initials “T N” appear on his arm) is the subject of an anatomy lesson (80).

The Reward of Cruelty: Nero

Paulson, Hogarth's Graphic Works

Nero's corpse, with the rope still around his neck, has accordingly been delivered for dissection. His initials "T N" are burnt on his arm. The assembled surgeons, wearing birettas and mortar boards, are enjoying their work as much as Nero enjoyed his in the first plate (215).

The Reward of Cruelty: Nero

Uglow

Tom’s end has come. In the ghastly final print he has been hanged, cut down and brought to the Surgeons’ Hall. The male body replaces the prone, murdered female. With horrific vitality Hogarth makes Tom’s corpse look alive, as if jerking up in pain as the surgeons probe his eye-sockets and excavate the delicate sinews of his ankles (504).

The Reward of Cruelty: Nero

Trusler

From the plate of execution the murderer is brought to Surgeons’-hall, and now represented under the knife of a dissector.

The gunpowder initials “T.N.” on the arm, denote this to be the body of Thomas Nero. The face being impressed with horror has been objected to. It must be acknowledged that this is rather o’erstepping the modesty of nature; but he so rarely deviates from her laws, that a little poetical license may be forgiven, where it produces humour or heightens character (135).

The Reward of Cruelty: Presiding

The setting is Surgeons’ Hall; the President’s chair bears the symbol of the Royal College of Physicians—highlighted by a pointing skeleton on either side of the room. Many commentators have observed the detachment of the onlookers: More appalling that the apathy of the spectators is the smug satisfaction of the man presiding over the event. Dressed as a magistrate and often identified as St. Bartholomew’s physician John Freke, he sits in absolute judgment over the scene, pointing to the now-empty chest cavity where Tom Nero’s cruel heart once resided.

The Reward of Cruelty: Presiding

Shesgreen

The anatomy lesson is narrative programmatically by an impassive figure. Above his head the emblem of the Royal College of Physicians depicting a doctor’s hand taking a pulse stands in contrast to the grotesque scene below (80).

The Reward of Cruelty: Presiding

Trusler

The skeletons on each side of the print, are inscribed “James Field” (an eminent pugilist), and “Maclean” (a notorious robber). Both of these worthies died by the rope. They are pointing to the physician’s crest, which is carved in the upper part of the president’s chair—viz., a hand feeling a pulse; taking a guinea would have been more appropriate to the practice. The heads of those two heroes of the halter are turned so as to seem ridiculing the president, “scoffing his state, and grinning at his pomp.” Every countenance in this grisly band is marked with that medical importance which dignifies the professors. Some of them we discover to be “from Caledonia’s bleak and barren clime” (135).