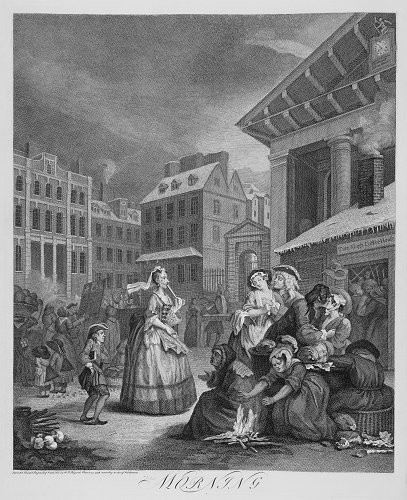

The Four Times of the Day: Morning

1738

17 15/16” X 14 13/16” (H X W)

View the full resolution plate here.

The "Morning" and "Noon" plates of The Four Times of the Day are typical of Hogarth's public groping scenes. In "Morning," two couples engage in open fondling and kissing. Trusler has noted the dichotomy between the "severe and stubborn virginity" of the woman going to church and the "poor girls who are suffering the embraces of two drunken beaux" (117). The chaos is contained within "Tom King's Coffee-House" but is imminent due to the lack of a happy medium as expressed in "Beer Street." Neither the virginity as embodied by the pious women nor the drunken excess as typified by the lovers provides the regulated sexuality that the English empire needs to provide growth yet sustain morality. The approaching danger is noted by Shesgreen who points out the presiding clock which reads "Sic Transit Gloria Mundi" (42).

Hogarth also condemns excessive, and hypocritical, piety. The old woman is alone, unprotected from the cold, while the others in the plate are warmed by their proximity to other human beings. She has closed herself off—sneering at the young lovers, ignoring the footboy and the beggar. Uglow notes that she is to represent, “Bridget Allworthy in Tom Jones. [but] Bridget, as the reader later discovers, is far from frigid, indeed she is full of desire, but she will not admit to it openly and her ‘prudence’ and desperate care for appearances almost ruins the life of her acknowledged son, as well as her own” (305).

The Four Times of the Day: Morning

Shesgreen, Sean. Engravings by Hogarth. (1973)

This print depicts the various activities of he people of Covent Garden on a winter’s morning. By the clock on Inigo Jones’ St. Paul’s it is 6:55 A.M. Through the center of the market walks a lady who austere countenance and fashionable dress are in marked contrast to those around her. Despite the snow and inclement weather, her affectation prompts her to expose her hands and bony chest to the cold. By her side dangles either a nutcracker or a pair of scissors in the form of a skeleton. Though on her way to church, she ignores the painful condition of the freezing page who carries her prayer book; she also evades the lance and outstretched hand of the beggar. She expresses on her face and with her fan moral horror at the activities of the engaging lovers in front of her. Behind the lovers the night’s festivities at “Tom King’s Coffee House” (purposefully eclipsing the church) conclude in a brawl which is about to erupt into the street.

Between the church and the tavern (the house with the large ale mug on a post and three small pitchers hanging from its eaves), a blind man escorted by a woman walks to church, and a porter rests to talk to another woman. To the left of the print’s judgmental figure, the day’s trade has begun. A large woman carts her vegetables to market on her head to the amazement of two little boys who lag in the square on their way to school. A quack with a bottle of “Dr. Rock’s” nostrum displays a billboard bearing the royal arms to suggest court patronage.

Two odd-shaped footprints near the page are marks made by iron mountings attached to shoes to keep the wearer above snow and mud.*

A statue of Time bearing a scythe and an hourglass stands in warning above the clock, and below it the motto “Sic Transit Gloria Mundi” (Thus passes the glory of the world) in inscribed in judgment on the scene (42).

*Lichtenberg, Lichtenberg’s Commentaries on Hogarth’s Engravings, p.215.

The Four Times of the Day: Morning

Quennell, Peter. Hogarth’s Progress. (1955)

With Times of the Day we return to London; and none of Hogarth’s London impressions is more evocative of the spirit of the time and place than the first of the series, which he entitled Morning. A wintry sky hangs over Covent Garden; according to the dial on the pediment of St. Paul’s Church, it is nearly seven o’clock. There is a feeling of snow in the air; a think crust of frozen snow has blanched the roofs and window-ledges; and icicles hang from the eaves of Tom King’s lowly coffee-house. Market-women arrive with baskets and lanterns; children, burdened by satchels, stump miserably away to school; and an elderly maiden lady (said the be a portrait of one of Hogarth’s relations, who, having recognized the likeness, immediately cut the artist out of her will.), her chilly footboy trudging behind her, hurries toward Early Service. To enter the church, she must pass Tom King’s, where, as we observe through the open door, a drunken brawl has suddenly exploded. A pair of young rakes, who have just emerged, fall upon two pretty girls; and the elderly devote lifts her fan to her lips, watching their struggles with a mixture of overt prudery and repressed amusement. In the engraved version, following his customary method, Hogarth has reversed the design; so that Lord Archer’s noble seventeenth-century mansion, of which traces still exist, appears on the wrong, or left-hand side, and Tom King’s on the extreme right. To see Morning at its best, a student must consult the picture –not only for the view of Covent Garden (which, despite many decades of re-building, bears a remarkable resemblance to the present market-place) but for the gaiety and subtlety of the painter’s colour-scheme. The background is a pattern of wintry tones—a huddle of drab-hued passers-by: a leaden firmament weighing heavily upon the spectral pallor of snow-bound roofs. But the foreground is alive with colour and movement; although the air is sharp and the light is dim, the young men from a night’s dissipation are full of zest and rowdy vigour, boldly towsling and bussing the girls, one of whom has a hat with a bright blue lining; while the scarlet ribbons of the church-goer’s cap match the spurting scarlet flames of the market-woman’s bonfire. Her expression, incidentally, is far less disdainful in the canvas than in the engraved plate; and she, too, has come out in her gayest plumage. She carries a fashionable ermine muff, and wears a pale pink apron over a champagne-yellow dress, which has trimmings of a delicate sea-green (149-150).

The Four Times of the Day: Morning

Uglow, Jenny. Hogarth: A Life and a World. (1997)

In Morning, Aurora, the goddess of dawn, steps out as a prudish English spinster heading to the temple-like front St. Paul’s, Covent Garden, with a shivering footboy instead of a chubby putti (303).

Here is Covent Garden on a snowy morning, its tall roofs soft with snow against a lowering sky, icicles hanging like lace from Tom King’s coffee house. The Church clock of St. Paul’s, surmounted by the grim reaper with his scythe, shows five minutes to eight. The market woman still needs her lantern as she carries her huge basket to her stall and children in stout coats, with bags on their back, sniff fresh-baked bread. Dr. Rock is already up selling his pills and in Tom King’s coffee house, a fight is going on, staves are waving in the shadowy entrance and a wig is flying through the air. (Perhaps the woman pleading is Moll King, who took over after her husband’s death in 1737. She made it a rule to open the door after the taverns closed, from midnight to dawn; the beaux went there straight from Court, in full dress with their swords, mingling in their rich brocaded coats with porters and soldiers and sweeps.) Hogarth shows the drooping-eyed rakes fondling their girls, their inner heat warding off the cold, while the scrawny older women crouch over the kindling, or raise a hand to beg.

If the scene was only this, then it might be called a documentary. But at the centre of the picture—and in the painting she focuses he light in her acid-lemon dress—stands a thin middle-aged woman on her way to church, touching her fan to her lips in apparent distaste at the display of young lust. As she judges them, she herself is implicitly condemned by her bony shape and her pursed lips, and by the young page who follows her, shivering in the cold, carrying her prayer under his arm: with a hint back to The Good Samaritan, the page, not the rich woman, is the one who has is the one who has his hand in his pocket, directly in line with the beggar woman’s outstretched palm. A hidden suggestion is that the prudish spinster in her finery who disdains charity and expresses dismay at amorous display may herself, secretly, be on the lookout for a lover. (Fielding took the measure of Hogarth’s judgement when he cited her in connection with Bridget Allworthy in Tom Jones. Bridget, as the reader later discovers, is far from frigid, indeed she is full of desire, but she will not admit to it openly and her “prudence” and desperate care for appearances almost ruins the life of her acknowledged son, as well as her own.)

At this stage, Hogarth did not wholly damn the loud life of the streets. Instead he judges those who judge, exposes the hypocrites, ridicules those who put form over feeling (303-305).

The Four Times of the Day: Morning

Paulson, Ronald. Hogarth’s Graphic Works. (1965)

Covent Garden in the morning (the buildings reversed): to the right is part of the façade of Inigo Jones’ church of St. Paul, which was burnt in 1795 and rebuilt by Thomas Hardwick. The church is obscured by “Tom King’s Coffee House,” a notorious tavern located conveniently close to Mother Douglas’ brothel. It opened its doors at midnight and continued into the morning. A large, obscene picture of a nun and a monk hung over the fireplace. At this time it was run by Tom’s widow, Moll King, who not long after the print’s appearance was fined and imprisoned (see the Weekly Miscellany, June 9, 1739). She retired to Hampstead, where she died, September 17, 1747. The tavern was celebrated in pamphlets called Tom K - - - 's: or the Paphian Grove. With the various Humours of Covent Garden, The Theatre, The Gaming Table, &c. A Mock Heroic Poem (1738) and A Night at Derry's, or the Ghost of Moll King's (1761); earlier Fielding referred to it in the prologue to The Covent Garden Tragedy (1732) and in Pasquin, I.i.(i736). Tom King's was actually on the south side of the square, not in front of St. Paul's; the juxtaposition is Hogarth's. The clock over the church portal shows 6:55; above it is Father Time, under it is "Sic Transit Gloria Mundi," and under that is smoke rising from Tom King's fireplace. A scuffle is going on inside and a wig flies out the open door. (For further information on Tom King's, see E. B. Chancellor, The Annals of Covent Garden, London, n.d., pp. 61-63.)

The lady walking to church, accompanied by her foot-boy who carries her prayer book, is the only person in the scene who does not notice the cold or try to ward it off. It is apparently her element. She pauses to regard (disapprovingly) the group that is composed of Tom King's, the two pairs of lovers, and the lower-class women and the beggar huddled about a fire. All of these people are getting warm in various ways (as is the foot-boy too, as best he can). The lady was used by Fielding as the model for his portrait of Bridget Allworthy (Tom Jones, Bk. I, Chap. 11) and by Cowper for his portrait of a prude in "Truth" (11. 131-70). She is said to have been based on a relation or acquaintance of Hogarth's who accordingly cut him out of her will (Gen. Works, I, 103). Hanging at her girdle is a pair of scissors, or perhaps a nutcracker, in the shape of a human skeleton. To the left are two boys on their way to school, watching a woman with a basket of vegetables on her head and a lantern at her girdle. A small crowd surrounds a quack (perhaps Dr. Rock himself), who hawks "Dr. Rock's" panacea (see Dr. Rock in Covent Garden, BM Sat. 2475; and Hogarth's Harlot's Progress, PI. 5, and The March to Finchley). The King's arms on his board (a lion and unicorn are discernible) show that his practice is sanctioned by royal letters patent. His panacea is intended as another way of escape from the winter. The pitcher on a tall post is a pewter measure which, like the smaller ones hanging from the eaves, signifies a public house.

In Morning he contrasts the pious old maid, standing alone and self-sufficient (the only person who does not feel the cold), with the drinking, love-making, begging crowd that is trying to keep warm; in the same way, the cold, geometrical facades of the church and other buildings are contrasted with the makeshift disorderly hulk of Moll King’s Tavern. The contrast is the point, and no judgment is made (178-179).

The Four Times of the Day: Morning

Paulson, Ronald. Hogarth: His Life, Art and Times. (1971)

In the first plate, the pious old maid stands alone, self-sufficient and unhelpful, outside the drinking, love-making, begging crowd that is trying to warm itself; in the same way, the face of the church is only another cold, geometrical façade above the makeshift, man-made hulk of Tom King’s tavern. Hogarth is . . . firmly on the side of nature . . . and strongly against the cold rigid church, but the contrast seems more the point here than a judgment. In a sense, the plate simply represents a bonfire with people huddled around trying to keep warm in the great empty square of Covent Garden, wit the church opposed to the tavern, the pious to the profane (vol. 1 404).

The Four Times of the Day: Morning

Dobson, Austin. William Hogarth. (1907)

The engravings of the Four Times of the Day are dated March 25, 1738. They represent three scenes in London and one at Islington; and the pictures . . .were reproduced by Hayman for Mr. Jonathan Tyers of Vauxhall. If only as transcripts of the time, they are extremely interesting. The first plate shows us Covent Garden at early morning on a winter’s day, with a disorderly company coming out of “Tom King’s Coffee House” (What rake is ignorant of King’s Coffee-house?”—asks Fielding in his Prologue to his Covent Garden Tragedy” of 1732, and he refers to it again four years later in “Pasquin,” where his “Comic Poet” is arrested as he leaves this disreputable resort. It stood, according to J.T. Smith, opposite to Tavistock Row, and not in front of the church, where, by artistic licence, Hogarth has placed it. Of Moll or Mary King, its proprietor at the date of this chapter, and a prosperous rival of the Needhams and Bentleys of her epoch, Mr. Edward Draper, of Vincent Square, Westminster, had a remarkable portrait, ascribed on good authority to Hogarth. In this she appears as a bold, handsome, gipsy-looking woman, holding a cat in her lap. After an ill-spent life, she died in retirement at Haverstock Hill, September 17, 1747).

But the cream of the character represented [in the series] is certainly the censorious prude in the first scene, with her lank-haired and shivering footboy. She is said to have been an aunt of the painter, who, like Churchill, lost a legacy by two inconsiderate a frankness. Fielding borrowed her starch lineaments for the portrait of Miss Bridget Allworthy, and Thackeray has copied her wintry figures of one of the initials to the “Roundabout Papers” (No. XI). To her, too, Cowper—whose early satires, like the poems of Crabbe, everywhere bear unmistakable traces of close familiarity with Hogarth—he has consecrated an entire passage of “Truth” (11.131-148):

Ton ancient prude, whose wither’d features show

She might be young some forty years ago,

Her elbows punion’d close upon her lips,

Her head erect, her fan upon her lips,

Her eyebrows arch’d, her eyes both gone astray

To watch you am’rous couple in their play,

With bony and unkerchief’d neck defies

The rude inclemency of wintry skies,

And sails with lappet-head and mincing airs

Duly, at clink of bell, to morning pray’rs.

To thrift and parsimony much inclin’d,

She yet allows herself that boy behind.

The shiv’ring urchin, bending as he goes,

With slip-shod heels and dew-drop at his nose,

His predecessor’s coat advanc’d to wear,

Which future pages yet are doom’d to share,

Carries her bible, tuck’d beneath his arm,

And hides his hands, to keep his fingers warm. (58-59).

The Four Times of the Day: Morning

Ireland, John and John Nichols. Hogarth’s Works. (1883)

This withered representative of Miss Bridget Alworthy, with a shivering footboy carrying her prayerbook, never fails in her attendance at morning service. She is a symbol of the season. “Chaste as the icicle/ That’s curled by the frost from purest snow,/ And hangs on Dian’s temple,” she looks with scowling eye, and all the conscious pride of severe and stubborn virginity, on the poor girls who are suffering the embraces of two drunken beaux that are just staggered out of Tom King’s Coffeehouse. One of them from the basket on her arm, I conjecture to be an orange-girl: she shows no displeasure at the boisterous salute of her Hibernian lover. That the hero in a laced hat is from the banks of the Shannon is apparent in his countenance. The female whose face is partly concealed, and whose neck has a more easy turn than we always see in the works of this artist, is not formed of the most inflexible materials.

An old woman, seated upon a basket; the girl warming her hands by a few withered sticks that are blazing on the ground; and a wretched mendicant, wrapped in a tattered and party-coloured blanket, entreating charity from the rosy-fingered vestal who is going to church, complete the group. Behind them, at the door of Tom King’s Coffeehouse, are a party engaged in a fray likely to create business for both surgeon and magistrate; we discover swords and cudgels in the combatants’ hands.

On the opposite side of the print are two little schoolboys. That they have shining morning faces we cannot positively assert, but each has a satchel at his back, and, according with the description given by the poet of nature, is “Creeping like snail unwillingly to school.”

The lantern appended to the woman who has a basket on her head, proves that these dispensers of the riches of Pomona rise before the sun, and do part of their business by an artificial light. Near her, that immediate descendant of Paracelsus, Doctor Rock, is expatiating to an admiring audience on the never-failing virtues of his wonder-working medicines. One hand holds a bottle of his miraculous panacea, and the other supports a board, on which is the king’s arms, to indicate that his practice is sanctioned by royal letters patent. Two porringers and a spoon, placed on the bottom of an inverted basket, intimate that the woman seated near them is a vendor of rice-milk, which was at that time brought into the market every morning.

A fatigued porter leans on a rail; and a blind beggar is going towards the church: but whether he will become one of the congregation, or take his stand at the door, in the hope that religion may have warmed the hearts of its votaries to “pity the sorrows of a poor blind man,” is uncertain.

The clock in the front of Inigo Jones’ barn has the motto of “SIC TRANSIT GLORIA MUNDI.” Had Mr. Hervey of Weston Favel written upon the works of Hogarth, he would have expatiated for ten pages upon the relation which this motto has to the smoke which is issuing from the chimney beneath; he would have written about it, and about it, and told his readers that the glory of the world is typified by the smoke, and like the smoke, it passeth away; that man himself is a mere vapour, etc. etc. etc.

Snow on the ground, and icicles hanging from the pent-house, exhibit a very chilling prospect; but, to dissipate the cold, there is happily a shop where spirituous liquors are sold pro bono publico, at a very little distance. A large pewter measure is placed upon a post before the door, and three of a smaller size hung over the window of the house.

The character of the principal figure (It has been said that this incomparable figure was designed as the representative of either a particular friend or a relation. . . . and it is related that Hogarth, by the introduction of this wretched votary of Diana into this print, induced her to alter a will which had been made considerably in his favour) is admirably delineated. She is marked with that prim and awkward formality which generally accompanies her order, and is an exact type of a hard winter; for every part of her dress, except the flying lappets and apron, ruffled by the wind, is as rigidly precise as if it were frozen. Extreme cold is very well expressed in the shipshod footboy (Of this there is an enlarged copy, which some of our collectors have ingeniously enough christened The Half-Starved Boy. It bears the date of 1730, and is inscribed “W.H. pinx. F. Sykes sc.” Sykes was the pupil of either Sir James Thornhill or Hogarth, and the 0 might have been intended for an 8 or a 9; but the aquafortis failing, it appears to have an earlier date than the print from which it was copied. If the date is right, Sykes undoubtedly copied it from a sketch of his master’s, which might then be unappropriated. In any case, it is too ridiculous to imagine for a moment that Hogarth was a plagiary; for supposing, what is not very probable that his pupil was capable of delineating the figure, he would scarcely have made the sketch without some concomitant circumstances to explain its meaning.), and the girl who is warming her hands. The group of which she is a part is well formed, but not sufficiently balanced on the opposite side.

The church dial, a few minutes before seven; marks of little shoes and pattens in the snow; and various productions of the season in the market, are an additional proof that minute accuracy with which this artist inspected and represented objects which painters in general have neglected.

Covent Garden is the scene, but in the print every building is reversed. This was a common error with Hogarth; not from his being ignorant of the use of the mirror, but from his considering it a matter of little consequence.

The propriety of exhibiting a scene of riot, in Tom King’s Coffeehouse is proved by the following quotation from the Weekly Miscellany for June 9, 1739:--“Monday, Mrs. Mary King, of Covent Garden, was brought up to the King’s Bench bar, at Westminster, and received the following sentence for keeping a disorderly house, viz. to pay a fine of two hundred pounds, and to suffer three months’ imprisonment, to find security for her good behaviour for three years, and to remain in prison till the fine be paid.” When her imprisonment ended, she retired from trade, built three houses on Haverstock Hill, near Hampstead, and in one of them, on the 10th of September 1747, she died. Her mansion was afterwards the residence of Nancy Dawson, and with the two others constitutes what is still distinguished by the appellation of Moll King’s Row (215-220).

The Four Times of the Day: Morning

Trusler, Rev. J. and E.F. Roberts. The Complete Works of William Hogarth. (1800)

Hogarth’s London, as he gives it us in substantial and easily recognisable fragments in his several pictures, is well worth looking into; a close and attentive study of which will amply satisfy the curious upon such matters. Looking upon it from Hogarth’s point of view, we find it to be neither Roman London nor Mediæval London, nor exactly “old world” London, in the express sense of the term; though somewhat of the skirts of that trim antiquity seem to hover about his transcripts. What we see of it is quaint, formal, picturesque, with ever so slight a smack of Dutch William’s tastes and pleasant architectural fancies; neat, as imported from the Hague, in steep-pitched roofs, and queer but striking gablings. It is all suggestive of gossip, of anecdote, of the wits at the coffee-house, of the literati, the artists, and the actors at Wills’, Buttons’s, and the Hummums. Covent Garden lies before us in all its unique graces of style, formal outlines, and memorable associations—no matter for the reversal of objects in the picture. We have a glimpse of St. Giles’s—not its more renowned and notorious point of attraction (Dyot Street), now gone and vanished with the “march of improvement” (whatever that tune is)—but the “Hog Lane” of his time—the Crown Street of the present day—and the French emigrants in sacques and hoods, in laced coats, and flourishing clouded canes, coming out of the Huguenot Chapel. He gives us next, in turn, a sweet suburban but, with grass and fresh water; and you hear the gentle low of the cows—a corner of New-River Head, be it known, not recognisable by Sadler’s Wells in 1860; but you see a but of the old theatre, and, very likely, you are carried back to the days of Joe Grimaldi. Charing Cross, again, is a spot far too well known, and even historical, to be overlooked; and, looking up a narrow street, now no longer existing, but which if rife with associations, quaint suggestions, and true Hogarthian vitality, we obtain a glimpse of the statue of Charles at the end, and thus our locality is fixed without possibility of misconception or error.

Covent Garden is the centre of much valuable memorabilia, and interesting reminiscences. The celebrities of days and eras, long gone into the past, are associated therewith. In the precincts of that noble ‘barn-like” church, reposes the dust of men who have been famous in their day—Estcourt, Edwin, Macklin, King, are names of renowned actors. Butler, the poet, lies there. Carr, Earl of Somerset, has there found a resting-place—Carr, who belongs to that hideously tragic story of Sir Thomas Overbury, and that dreadful Countess of Somerset. This Carr had a daughter, who was married to William, Earl and Duke of Bedford; and who has been brought up in such thorough ignorance of the shame and dishonour of her parents, that having, by chance, met with a book in which the whole stark-naked horror of the appalling crime was set forth, she was found in a dead faint on the floor; and the story coloured the whole of her after-life with a touch of gloom.

Here lies the gay and airy Wycherley, whose muse was so flaunting, and whose cheeks were tinted with rouge and ruddy wine. Here, too, rest Peter Lely, who painted a brazen sisterhood, so meretricious and deboshed, that it is only by degrees of strumpetry they are recognisable the one from the other; Southern, Sir Robert Strange (the greatest engraver we have known); Peter Pindar (Dr. Wolcot), and many more. Here, too, opposite the Bedford Coffee-house, occurred a fearful tragedy—the assassination of Miss Ray (a beautiful and accomplished young lady, protected by the Earl of Sandwich), by a Captain Hackman, in a fit of jealousy; the whole story itself being of the most romantic and startling nature.

It would be but multiplying instances to quote names, anecdotes, and “recollections,” all of which go to prove Covent Garden to be a sort of classic ground, rendered doubly so by the stately tread of Sir Roger de Coverley, or of his representative, Mr. Joseph Addison. And beside that erect figure stalks the burlier Sir Richard Steele, with a merry twinkle in his eye, and a harmless jest for the orange girl on the piazza, who solicits him to purchase. “Glorious John,” in his pride and in his prime, makes no insignificant show as he crosses that queer quadrangle, which is now so different, with its floral arcades, from the vanity of earthly things; Oliver Goldsmith exhibits his plum-coloured suit; David Garrick passes, with measured step, that way, theatre-ward; Sir Joshua Reynolds is going to the club; and here comes Bozzy, full of fresh matter—droppings of wisdom, and curt apothegms, which the great lexicographer has just given utterance to. It is now time that the picture should speak for itself; for it is far from being deficient in an eloquence which appeals to us in an infinite variety of ways.

Morning, in Covent Garden, looks wintry and lowering enough (116-117).

The Four Times of the Day: Morning

Lichtenberg, G. Ch. Lichtenberg’s Commentaries on Hogarth’s Engravings. (1784-1796). Translated from the German by Innes and Gustav Herdan (1966)

Hogarth, who had a very good sense of what many a writer and artist prefers to ignore, that is, the part for which Nature had intended him, has chosen to represent this time of the day, not by any of the great soul- uplifting scenes of a spring or summer morning, but a winter one, and there again, not the funereal pomp of the frost-encrusted bushes where winter sleeps until its resurrection, or the pine forest moaning under its flaky burden of snow, but—Covent Garden vegetable market in London. That is where he feels at home. What, in fact, could his particular genius have made of a May morning in the country? No doubt a few wretched nightingale catchers with their all-too-familiar courtier faces, enticing those sweet songstresses into a trap without even noticing that the sun is rising over their noble occupation; or a few belles of doubtful reputation engaged in emptying bottles of May dew over one another's heads, with gestures and grimaces which no May dew will ever wash off. What he would make of a winter landscape, the reader will be able to surmise from what he is going to see and read here about a winter morning at the vegetable market.

It is just eight, as can be seen from the church clock, very cold, and snow has fallen. The impressions which we observe in the foreground come from the iron mounting of small wooden shoes (pattens) which were then worn by the female population, and enabled them to glide, to the advantage of shoes and feet, a few inches above the mud of the streets. These were the sort of footprints they made in the year 1738; now everything is more civilized. The clatter made by these little horse-shoes on the London pavements is by no means disagreeable to a stranger's ear especially if-as is mostly the case-the pedestrians are pretty Did one not see that they were pedestrians, one might sometimes take them for cavalry approaching, at least light cavalry.

The main figure in the whole picture for which all the other splendours of the winter sky and the winter earth with its snow and riches serve only as a frame, so to speak, is the lovely pedestrian in the centre. You can see she is already beyond the first stage of a religious devotee whose double duty, toward heaven and her neighbour, she has this morning partly fulfilled, and partly is about to fulfil. She is on her way to church and at a time of day and year when even the decision to do so proclaims a sanctity which was never imparted to a wholly sinful heart; and how much does she not care for her neighbour! For to be sure, she would not doll herself up like that for her own benefit. She must have started already at four o clock that morning, thus by artificial light; we cannot be surprised, therefore, if in practice everything has not turned out exactly as theory intended it should. It is a well-known principle in the building of kitchens that they should be light enough not to need any artificial light during daytime. But anything which is prepared by artificial light can as a rule, be served to advantage only under such light; and by this token I should imagine that the lady might be acceptable by candlelight We must also take the season into account here; the brightness of the snow as well as the cold are not at all favourable for certain little flowers- only peach blossoms thrive in the snow. But now to the subject in a more serious vein and in a manner more worthy of it. We have here, in the year 1738 a lady who would still like to look what it was already too late for at the end of the last century--charming. Beauty spots (mouches) float about her gleaming eye like midges round a candle flame, a warning to any young man whose glances would like to imitate them. On her cheek of course, one notices something like a birth certificate in indelible writing But it is not really that; there are wrinkles, it is true, but they spring surely from the comers of the mouth where Cupid plays his little pranks.

This gentle play communicates itself to the cheeks in tiny waves which propagating more and more, like ripples, withdraw finally behind the ears. Even the bosom still shows its gentle undulation, although there the ice is already forming. The right arm wears its winter garment quite negligently and easily, while the hand with the fan (in winter!) succours the lip which with that strained smile is no longer able by itself to cover the gap in the teeth. However, only two fingers are needed to look after both, fan and lip. How daintily this charming damsel handles everything! I can wager that lip grips its syllables just like the hand does its fan. The way she holds her neck is a master stroke, especially when combined with the gentle inclination of the upper part other body. It seems as if the neck, through gentle elastic opposition, would promote the glorious waving of the pennant which flows out there from the gable into the morning air. What a pity it is that pennants have gone out of fashion! The times are not what they were, to be sure; nowadays, when Divine Service has ended, the procession looks just about as brilliant as a queue for alms; in the old days it used to look like a fleet setting sail with all the world's splendour on board. Wherever it sailed, victory attended. Everybody saluted and everybody struck—the hat; it was irresistible.

The lady is not only unmarried—but has never been married. All the interpreters agree in this, and I must confess I have no objection to raise. Whoever has long been a spinster, with all the little fineries which that state unfortunately entails, gets to like them in the end; indeed, the little bits of affectation increase since they become more and more necessary and cease only with the end of the spinsterhood, or with the spinster herself. This is as human as it can be. I should not like to decide whether even the wisest of men, were he to live for five hundred years like Cagliostro, in order to 'sell' his higher wisdom, would not also make an advertising face in the end, which would appear to our more naive philosophers, or to the angels in Heaven, like the face of that spinster. Merely through force of habit man cannot become better on his way through life, and to get over this he must first die. I also seem to remember that somebody has called the day of death a wedding day. Les beaux esprits se rencontrent—just like philosophy and spinsterhood.

What may have been responsible for the definite opinion of the interpreters is perhaps the excessive dryness of the subject. Nichols even calls her 'the exhausted representative of involuntary spinsterhood'. Of course, all prolonged tending of fire is bad for the health, and none more so than that of the Vestals' fire. Just as ordinary metal smelters are subject to lead poisoning, an occupational disease of foundry work, so are the heart smelters to what one might call the Vestals' occupational disease. But— by God! the former still leave us the metal, whereas with the latter both smelter and metal are lost. Have mercy on them! would I exclaim over their bosoms had I not just noticed in that saint's eye a glance at the scene in front of Tom King's Coffee House, which stifles my pity. All is not yet lost. Sounding boards are no impediment to happiness in married life. The dull murmur of reproach achieves distinctness thereby, the private sermonizing obtains more life, and the orders to the servants the needful volume upstairs and down, without all of which no household can exist. The wooden figure as it stands there has cost our good artist rather dear; it is in fact the portrait of an old spinster with whom he was, if not exactly related, at least very well acquainted. She is said to have been quite content at first with her role in the work of her friend, probably on account of its close similarity to the beloved original. A sentiment of such rare good nature, though based only upon ignorance of worldly intrigues, would have well merited Hogarth's blotting out the figure of the heroine who had expressed it. But that certain type of good friend who is never missing persuaded him to leave the magnificent figure, not without endeavouring, at the same time, to enlighten the lady as to the scandal of such a procedure, and with such good effect that in the end her portrait remained, but on account of it Hogarth was blotted out from the matron's Last Will, in which he would gladly have remained, she having rather handsomely provided for him there. Whoever hopes to inherit something from an old aunt should beware of making any satires upon women over fifty, but should be the ruder to all under forty. Readers of Tom Jones will remember here that Fielding, when he describes the appearance of Tom's and Blifield's mother, expressly states that she looked like this lady, and Fielding, as one knows, read her character very well. Tom Jones is twice as entertaining to read if one knows this.

The lad, or whoever it is behind her, is her attendant. The poor devil appears to have been put not only upon half-rations, but upon half-livery too, which in addition, as a donatio inter vivos in linea recta descendente, seems to have been handed down from his sixth predecessor. He wears slippers only. His feet are frozen anyway. In the Taschenkalender I have said that he has no stockings on. For this I was criticized by an Englishman of mature judgment; such a thing, he said, would be unheard of in England. The mistake is easily corrected: I have only to say that he presumably wears stockings. A more miserable, starving, and frozen object would be hard to imagine; in such circumstances, of course that inner peace cannot fail him which here plays about his eyes and lips. Under his arm he carries a voluminous prayer-book, apparently the only comfort which his mistress has vouchsafed him against all this misfortune That is how the old, rich aunts behave, especially about the time when they are laying their Last Will; they hatch them better that way too.

On the left-hand side, as if built against St Paul's Church (St Paul's Covent Garden-not to be confused with the famous one in the City), stands Tom King's Coffee House. Hogarth has intentionally selected his viewpoint so that this den looks as if it were the sacristy of the Church. It was, strictly speaking, only a miserable shed whose chimney was lower than the epistyle of the porch in that fine church. The debaucheries which were enacted here and which not infrequently ended in murder are indescribable. After Tom King’s death, the virtuous widow, who apparently stands there in the doorway, continued the evil business until at last justice roused itself. It is probable that Hogarth has by this picture contributed not a little to her awakening. A marvellous subject for the satiric artist! To get the matter talked about in public houses as well as at the dinner table of the mighty cost him only a few lines with the etching needle. The London police force is a stern, clever and order-loving lady, but it fares with her as with many other honest person: her servant are sometimes the devil of a use to her. Thus something may cry out to Heaven for a long time without its being heard in the very next court of law. I say it is probable that Hogarth helped to arouse justice; for these engravings appeared towards the end of the year 1738, and in June 1739 Madame King was arrested. Her sentence was: she was to raze the “sacristy” to the ground, pay a fine of £200, go to Newgate for three months, and if then the fine was still unpaid, she was to stay there until she had forked out the last penny; apart from all this, she was to give security with a considerable sum to be on conduct for the next three years. This is an excellent expedient of English justice for clipping the wings of people who have strayed into such an occupation. For should they stray again, the security will be lost, and justice will then, as a rule, cut a little deeper still, or will even hang the little bird without further clipping, according to circumstances. However, Madame King paid up and conducted herself well, and with the remaining offertory pennies from St Paul's Church built three cottages not far from Hampstead, a village near London set upon a charming hill; to this day these are still called Moll King's Row. There, in September 1747, she died, apparently in her bed. From the fine imposed on her, as well as from the offertory pennies, the reader will be able to judge for himself what may have been going on in close vicinity to the columns of that house of the Lord.

The nest has opened just now; the proceedings must have been pretty warm in there last night, for they have melted even the snow upon the roof. First to be flung out is a wig of some standing, though a false friend to its master whom it has deserted in time of trouble, leaving his bald head under a hail of blows instead of helping to ward them off. There is something very funny about the flight of that wig. Had it been a learned company which is being conducted to the door there, one might, at least in the half-light, almost take it for Minerva's bird that had presided over the night's proceedings, or for a lyre which like Spenser's harp rises to Heaven to greet the morning star. The van of the company which is spewed out here hurl themselves like liberated beasts upon a couple of innocent creatures, one of whom has come here to sell garden plants and the other, with the basket upon her arm, to shop, and who have arrived thus early. The fellow with the braided hat is said to be Irish: his wig has remained faithful to him, but it has suffered not a little in service. In any other place than upon a head it would hardly be regarded as a wig at all. Next to the fire sits a creature who would surely be much flattered if we said that she looks almost human. She seems to be dumb, or else her vocal chords have perhaps suffered in a fight, for like a medicine bottle she wears a label round her neck upon which is written what is to be found there. It is her history, though it is not this which she presents to the old spinster, but the abominable facts themselves—her face. She is a beggar; can she entertain any hopes, seeing the beggar in livery? But he addresses himself only to his mistress's love of mankind and freezes for it. And here in public something may be expected from vanity enhanced by publicity.

In the background stands the notorious French-pox doctor Rock with his notice-board and his little potions and lotions, advertising himself and his medicines, to those who have fallen for the temptations of the illness in which he deals. In spite of its being so early and cold, he already has an audience, among them a woman wearing a hood because of the cold and the onlookers. Doctor Rock is said to be a true likeness, in spite of being a portrait delineated with so few strokes. Hogarth is extraordinarily gracious towards this man; he uses every opportunity of recommending him to posterity. What can he have done for him?

In front of that group we see, quite charmingly observed, two little schoolboys who, with their satchels like snailshells on their backs, are 'creeping like snails unwillingly to school'. At the moment this is done by staying put. Their attention seems to have been caught by a lighted lantern which a very energetic and heavily laden woman, who must have started on her way before daybreak, has hung upon herself. Between the hands of the clock and the rising smoke are the words sic transit gloria mundi; thus it is a choice between vapour and the moving hands of the clock; passing splendour with or without hope of return. I believe that small reminder from above is directed at the top mast with the pennant. Poor auntie! she will probably have to grasp the smoke. In Cowper's poem (Vol. I, p. 80), there is a very good description of the old spinster and her servant in ten-syllable rhymed iambics which well deserve to be looked up (275-281)..

The Four Times of the Day: Morning: Beggar

A beggar is ignored by the “pious” old woman.

The Four Times of the Day: Morning: Beggar

Ireland

a wretched mendicant , wrapped in a tattered and party-coloured blanket, entreating charity from the rosy-fingered vestal who is going to church, complete the group (216-217).

The Four Times of the Day: Morning: Beggar

Lichtenberg

Next to the fire sits a creature who would surely be much flattered if we said that she looks almost human. She seems to be dumb, or else her vocal chords have perhaps suffered in a fight, for like a medicine bottle she wears a label round her neck upon which is written what is to be found there. It is her history, though it is not this which she presents to the old spinster, but the abominable facts themselves—her face. She is a beggar; can she entertain any hopes, seeing the beggar in livery? But he addresses himself only to his mistress's love of mankind and freezes for it. And here in public something may be expected from vanity enhanced by publicity (280).

The Four Times of the Day: Morning: Fighting

Uglow

in Tom King’s coffee house, a fight is going on, staves are waving in the shadowy entrance and a wig is flying through the air.(Perhaps the woman pleading is Moll King, who took over after her husband’s death in 1737. She made it a rule to open the door after the taverns closed, from midnight to dawn; the beaux went there straight from Court, in full dress with their swords, mingling in their rich brocaded coats with porters and soldiers and sweeps.) (305).

The Four Times of the Day: Morning: Fighting

Paulson, Hogarth's Graphic Works

The church is obscured by “Tom King’s Coffee House,” a notorious tavern located conveniently close to Mother Douglas’ brothel. It opened its doors at midnight and continued into the morning. A large, obscene picture of a nun and a monk hung over the fireplace. At this time it was run by Tom’s widow, Moll King, who not long after the print’s appearance was fined and imprisoned (see the Weekly Miscellany, June 9, 1739). She retired to Hampstead, where she died, September 17, 1747. The tavern was celebrated in pamphlets called Tom K - - - 's: or the Paphian Grove. With the various Humours of Covent Garden, The Theatre, The Gaming Table, &c. A Mock Heroic Poem (1738) and A Night at Derry's, or the Ghost of Moll King's (1761); earlier Fielding referred to it in the prologue to The Covent Garden Tragedy (1732) and in Pasquin, I.i.(i736). Tom King's was actually on the south side of the square, not in front of St. Paul's; the juxtaposition is Hogarth's (178-179)..

A scuffle is going on inside and a wig flies out the open door. (For further information on Tom King's, see E. B. Chancellor, The Annals of Covent Garden, London, n.d., pp. 61-63.) (179).

The Four Times of the Day: Morning: Fighting

Dobson

The first plate shows us Covent Garden at early morning on a winter’s day, with a disorderly company coming out of “Tom King’s Coffee House” (What rake is ignorant of King’s Coffee-house?”—asks Fielding in his Prologue to his Covent Garden Tragedy” of 1732, and he refers to it again four years later in “Pasquin,” where his “Comic Poet” is arrested as he leaves this disreputable resort. It stood, according to J.T. Smith, opposite to Tavistock Row, and not in front of the church, where, by artistic licence, Hogarth has placed it. Of Moll or Mary King, its proprietor at the date of this chapter, and a prosperous rival of the Needhams and Bentleys of her epoch, Mr. Edward Draper, of Vincent Square, Westminster, had a remarkable portrait, ascribed on good authority to Hogarth. In this she appears as a bold, handsome, gipsy-looking woman, holding a cat in her lap. After an ill-spent life, she died in retirement at Haverstock Hill, September 17, 1747) (58).

The Four Times of the Day: Morning: Fighting

Ireland

Behind them, at the door of Tom King’s Coffeehouse, are a party engaged in a fray likely to create business for both surgeon and magistrate; we discover swords and cudgels in the combatants’ hands (217).

The propriety of exhibiting a scene of riot, in Tom King’s Coffeehouse is proved by the following quotation from the Weekly Miscellany for June 9, 1739:--“Monday, Mrs. Mary King, of Covent Garden, was brought up to the King’s Bench bar, at Westminster, and received the following sentence for keeping a disorderly house, viz. to pay a fine of two hundred pounds, and to suffer three months’ imprisonment, to find security for her good behaviour for three years, and to remain in prison till the fine be paid.” When her imprisonment ended, she retired from trade, built three houses on Haverstock Hill, near Hampstead, and in one of them, on the 10th of September 1747, she died. Her mansion was afterwards the residence of Nancy Dawson, and with the two others constitutes what is still distinguished by the appellation of Moll King’s Row (220).

The Four Times of the Day: Morning: Fighting

Lichtenberg

The nest has opened just now; the proceedings must have been pretty warm in there last night, for they have melted even the snow upon the roof. First to be flung out is a wig of some standing, though a false friend to its master whom it has deserted in time of trouble, leaving his bald head under a hail of blows instead of helping to ward them off. There is something very funny about the flight of that wig. Had it been a learned company which is being conducted to the door there, one might, at least in the half-light, almost take it for Minerva's bird that had presided over the night's proceedings, or for a lyre which like Spenser's harp rises to Heaven to greet the morning star. The van of the company which is spewed out here hurl themselves like liberated beasts upon a couple of innocent creatures, one of whom has come here to sell garden plants and the other, with the basket upon her arm, to shop, and who have arrived thus early (280).

The Four Times of the Day: Morning: Kids

Ireland

On the opposite side of the print are two little schoolboys. That they have shining morning faces we cannot positively assert, but each has a satchel at his back, and, according with the description given by the poet of nature, is “Creeping like snail unwillingly to school” (217).

The Four Times of the Day: Morning: Kids

Lichtenberg

In front of that group we see, quite charmingly observed, two little schoolboys who, with their satchels like snailshells on their backs, are 'creeping like snails unwillingly to school'. At the moment this is done by staying put. Their attention seems to have been caught by a lighted lantern which a very energetic and heavily laden woman, who must have started on her way before daybreak, has hung upon herself (281).

The Four Times of the Day: Morning: Lovers

The "Morning" and "Noon" plates of The Four Times of the Day are typical of Hogarth's public groping scenes. In "Morning," two couples engage in open fondling and kissing. Trusler has noted the dichotomy between the "severe and stubborn virginity" of the woman going to church and the "poor girls who are suffering the embraces of two drunken beaux" (117).

Neither the virginity as embodied by the pious women nor the drunken excess as typified by the lovers provides the regulated sexuality that the English empire needs to provide growth yet sustain morality.

The Four Times of the Day: Morning: Lovers

Quennell

A pair of young rakes, who have just emerged, fall upon two pretty girls (149).

The Four Times of the Day: Morning: Lovers

Uglow

Hogarth shows the drooping-eyed rakes fondling their girls, their inner heat warding off the cold (305).

The Four Times of the Day: Morning: Lovers

Ireland

poor girls who are suffering the embraces of two drunken beaux that are just staggered out of Tom King’s Coffeehouse. One of them from the basket on her arm, I conjecture to be an orange-girl: she shows no displeasure at the boisterous salute of her Hibernian lover. That the hero in a laced hat is from the banks of the Shannon is apparent in his countenance. The female whose face is partly concealed, and whose neck has a more easy turn than we always see in the works of this artist, is not formed of the most inflexible materials (216).

The Four Times of the Day: Morning: Lovers

Lichtenberg

The van of the company which is spewed out here hurl themselves like liberated beasts upon a couple of innocent creatures, one of whom has come here to sell garden plants and the other, with the basket upon her arm, to shop, and who have arrived thus early. The fellow with the braided hat is said to be Irish: his wig has remained faithful to him, but it has suffered not a little in service. In any other place than upon a head it would hardly be regarded as a wig at all (280).

The Four Times of the Day: Morning: Old Woman

Trusler has noted the dichotomy between the "severe and stubborn virginity" of the woman going to church and the "poor girls who are suffering the embraces of two drunken beaux” (117).

Hogarth also condemns excessive, and hypocrital, piety. The old woman is alone, unprotected from the cold, while the others in the plate are warmed by their proximity to other human beings. She has closed herself off—sneering at the young lovers, ignoring the footboy and the beggar. Uglow notes that she is to represent, “Bridget Allworthy in Tom Jones. [but] Bridget, as the reader later discovers, is far from frigid, indeed she is full of desire, but she will not admit to it openly and her ‘prudence’ and desperate care for appearances almost ruins the life of her acknowledged son, as well as her own” (305).

The Four Times of the Day: Morning: Old Woman

Shesgreen

Through the center of the market walks a lady who austere countenance and fashionable dress are in marked contrast to those around her. Despite the snow and inclement weather, her affectation prompts her to expose her hands and bony chest to the cold. By her side dangles either a nutcracker or a pair of scissors in the form of a skeleton. Though on her way to church, she ignores the painful condition of the freezing page who carries her prayer book; she also evades the lance and outstretched hand of the beggar. She expresses on her face and with her fan moral horror at the activities of the engaging lovers in front of her (42).

The Four Times of the Day: Morning: Old Woman

Quennell

An elderly maiden lady (said the be a portrait of one of Hogarth’s relations, who, having recognized the likeness, immediately cut the artist out of her will.), with her chilly footboy trudging behind her, hurries towards Early Service (149).

The elderly dévote lifts her fan to her lips, watching their struggles with a mixture of overt prudery and repressed amusement (149).

The Four Times of the Day: Morning: Old Woman

Uglow

In Morning, Aurora, the goddess of dawn, steps out as a prudish English spinster heading to the temple-like front St. Paul’s, Covent Garden, with a shivering footboy instead of a chubby putti (303).

If the scene was only this, then it might be called a documentary. But at the centre of the picture—and in the painting she focuses he light in her acid-lemon dress—stands a thin middle-aged woman on her way to church, touching her fan to her lips in apparent distaste at the display of young lust. As she judges them, she herself is implicitly condemned by her bony shape and her pursed lips, and by the young page who follows her, shivering in the cold, carrying her prayer under his arm: with a hint back to The Good Samaritan, the page, not the rich woman, is the one who has is the one who has his hand in his pocket, directly in line with the beggar woman’s outstretched palm. A hidden suggestion is that the prudish spinster in her finery who disdains charity and expresses dismay at amorous display may herself, secretly, be on the lookout for a lover. (Fielding took the measure of Hogarth’s judgement when he cited her in connection with Bridget Allworthy in Tom Jones. Bridget, as the reader later discovers, is far from frigid, indeed she is full of desire, but she will not admit to it openly and her “prudence” and desperate care for appearances almost ruins the life of her acknowledged son, as well as her own.) (305).

The Four Times of the Day: Morning: Old Woman

Paulson, Hogarth's Graphic Works

The lady walking to church, accompanied by her foot-boy who carries her prayer book, is the only person in the scene who does not notice the cold or try to ward it off. It is apparently her element. She pauses to regard (disapprovingly) the group that is composed of Tom King's, the two pairs of lovers, and the lower-class women and the beggar huddled about a fire. All of these people are getting warm in various ways (as is the foot-boy too, as best he can). The lady was used by Fielding as the model for his portrait of Bridget Allworthy (Tom Jones, Bk. I, Chap. 11) and by Cowper for his portrait of a prude in "Truth" (11. 131-70). She is said to have been based on a relation or acquaintance of Hogarth's who accordingly cut him out of her will (Gen. Works, I, 103). Hanging at her girdle is a pair of scissors, or perhaps a nutcracker, in the shape of a human skeleton (179).

The Four Times of the Day: Morning: Old Woman

Dobson

But the cream of the character represented [in the series] is certainly the censorious prude in the first scene, with her lank-haired and shivering footboy. She is said to have been an aunt of the painter, who, like Churchill, lost a legacy by two inconsiderate a frankness. Fielding borrowed her starch lineaments for the portrait of Miss Bridget Allworthy, and Thackeray has copied her wintry figures of one of the initials to the “Roundabout Papers” (No. XI). To her, too, Cowper—whose early satires, like the poems of Crabbe, everywhere bear unmistakable traces of close familiarity with Hogarth—he has consecrated an entire passage of “Truth” (11.131-148):

Ton ancient prude, whose wither’d features show

She might be young some forty years ago,

Her elbows punion’d close upon her lips,

Her head erect, her fan upon her lips,

Her eyebrows arch’d, her eyes both gone astray

To watch you am’rous couple in their play,

With bony and unkerchief’d neck defies

The rude inclemency of wintry skies,

And sails with lappet-head and mincing airs

Duly, at clink of bell, to morning pray’rs.

To thrift and parsimony much inclin’d,

She yet allows herself that boy behind.

The shiv’ring urchin, bending as he goes,

With slip-shod heels and dew-drop at his nose,

His predecessor’s coat advanc’d to wear,

Which future pages yet are doom’d to share,

Carries her bible, tuck’d beneath his arm,

And hides his hands, to keep his fingers warm. (59)

The Four Times of the Day: Morning: Old Woman

Ireland

This withered representative of Miss Bridget Alworthy, with a shivering footboy carrying her prayerbook, never fails in her attendance at morning service. She is a symbol of the season. “Chaste as the icicle/ That’s curled by the frost from purest snow,/ And hangs on Dian’s temple,” she looks with scowling eye, and all the conscious pride of severe and stubborn virginity, on the poor girls who are suffering the embraces of two drunken beaux that are just staggered out of Tom King’s Coffeehouse (215-216).

The character of the principal figure (It has been said that this incomparable figure was designed as the representative of either a particular friend or a relation. . . . and it is related that Hogarth, by the introduction of this wretched votary of Diana into this print, induced her to alter a will which had been made considerably in his favour) is admirably delineated. She is marked with that prim and awkward formality which generally accompanies her order, and is an exact type of a hard winter; for every part of her dress, except the flying lappets and apron, ruffled by the wind, is as rigidly precise as if it were frozen (218-219).

The Four Times of the Day: Morning: Old Woman

Lichtenberg

The main figure in the whole picture for which all the other splendours of the winter sky and the winter earth with its snow and riches serve only as a frame, so to speak, is the lovely pedestrian in the centre. You can see she is already beyond the first stage of a religious devotee whose double duty, toward heaven and her neighbour, she has this morning partly fulfilled, and partly is about to fulfil. She is on her way to church and at a time of day and year when even the decision to do so proclaims a sanctity which was never imparted to a wholly sinful heart; and how much does she not care for her neighbour! For to be sure, she would not doll herself up like that for her own benefit. She must have started already at four o clock that morning, thus by artificial light; we cannot be surprised, therefore, if in practice everything has not turned out exactly as theory intended it should. It is a well-known principle in the building of kitchens that they should be light enough not to need any artificial light during daytime. But anything which is prepared by artificial light can as a rule, be served to advantage only under such light; and by this token I should imagine that the lady might be acceptable by candlelight We must also take the season into account here; the brightness of the snow as well as the cold are not at all favourable for certain little flowers- only peach blossoms thrive in the snow. But now to the subject in a more serious vein and in a manner more worthy of it. We have here, in the year 1738 a lady who would still like to look what it was already too late for at the end of the last century--charming. Beauty spots (mouches) float about her gleaming eye like midges round a candle flame, a warning to any young man whose glances would like to imitate them. On her cheek of course, one notices something like a birth certificate in indelible writing But it is not really that; there are wrinkles, it is true, but they spring surely from the comers of the mouth where Cupid plays his little pranks.

This gentle play communicates itself to the cheeks in tiny waves which propagating more and more, like ripples, withdraw finally behind the ears. Even the bosom still shows its gentle undulation, although there the ice is already forming. The right arm wears its winter garment quite negligently and easily, while the hand with the fan (in winter!) succours the lip which with that strained smile is no longer able by itself to cover the gap in the teeth. However, only two fingers are needed to look after both, fan and lip. How daintily this charming damsel handles everything! I can wager that lip grips its syllables just like the hand does its fan. The way she holds her neck is a master stroke, especially when combined with the gentle inclination of the upper part other body. It seems as if the neck, through gentle elastic opposition, would promote the glorious waving of the pennant which flows out there from the gable into the morning air. What a pity it is that pennants have gone out of fashion! The times are not what they were, to be sure; nowadays, when Divine Service has ended, the procession looks just about as brilliant as a queue for alms; in the old days it used to look like a fleet setting sail with all the world's splendour on board. Wherever it sailed, victory attended. Everybody saluted and everybody struck—the hat; it was irresistible.

The lady is not only unmarried—but has never been married. All the interpreters agree in this, and I must confess I have no objection to raise. Whoever has long been a spinster, with all the little fineries which that state unfortunately entails, gets to like them in the end; indeed, the little bits of affectation increase since they become more and more necessary and cease only with the end of the spinsterhood, or with the spinster herself. This is as human as it can be. I should not like to decide whether even the wisest of men, were he to live for five hundred years like Cagliostro, in order to 'sell' his higher wisdom, would not also make an advertising face in the end, which would appear to our more naive philosophers, or to the angels in Heaven, like the face of that spinster. Merely through force of habit man cannot become better on his way through life, and to get over this he must first die. I also seem to remember that somebody has called the day of death a wedding day. Les beaux esprits se rencontrent—just like philosophy and spinsterhood.

What may have been responsible for the definite opinion of the interpreters is perhaps the excessive dryness of the subject. Nichols even calls her 'the exhausted representative of involuntary spinsterhood'. Of course, all prolonged tending of fire is bad for the health, and none more so than that of the Vestals' fire. Just as ordinary metal smelters are subject to lead poisoning, an occupational disease of foundry work, so are the heart smelters to what one might call the Vestals' occupational disease. But— by God! the former still leave us the metal, whereas with the latter both smelter and metal are lost. Have mercy on them! would I exclaim over their bosoms had I not just noticed in that saint's eye a glance at the scene in front of Tom King's Coffee House, which stifles my pity. All is not yet lost. Sounding boards are no impediment to happiness in married life. The dull murmur of reproach achieves distinctness thereby, the private sermonizing obtains more life, and the orders to the servants the needful volume upstairs and down, without all of which no household can exist. The wooden figure as it stands there has cost our good artist rather dear; it is in fact the portrait of an old spinster with whom he was, if not exactly related, at least very well acquainted. She is said to have been quite content at first with her role in the work of her friend, probably on account of its close similarity to the beloved original. A sentiment of such rare good nature, though based only upon ignorance of worldly intrigues, would have well merited Hogarth's blotting out the figure of the heroine who had expressed it. But that certain type of good friend who is never missing persuaded him to leave the magnificent figure, not without endeavouring, at the same time, to enlighten the lady as to the scandal of such a procedure, and with such good effect that in the end her portrait remained, but on account of it Hogarth was blotted out from the matron's Last Will, in which he would gladly have remained, she having rather handsomely provided for him there. Whoever hopes to inherit something from an old aunt should beware of making any satires upon women over fifty, but should be the ruder to all under forty. Readers of Tom Jones will remember here that Fielding, when he describes the appearance of Tom's and Blifield's mother, expressly states that she looked like this lady, and Fielding, as one knows, read her character very well. Tom Jones is twice as entertaining to read if one knows this (276-278).

The Four Times of the Day: Morning: Sign

Even the quacks get an early start: Dr. Rock sets up shop, selling his “panacea.” He is also featured in A Harlot’s Progress.

The Four Times of the Day: Morning: Sign

Paulson, Hogarth's Graphic Works

A small crowd surrounds a quack (perhaps Dr. Rock himself), who hawks "Dr. R ock's" panacea. (see Dr. Rock in Covent Garden, BM Sat. 2475; and Hogarth's Harlot's Progress, PI. 5, and The March to Finchley). The King's arms on his board (a lion and unicorn are discernible) show that his practice is sanctioned by royal letters patent. His panacea is intended as another way of escape from the winter (179).

The Four Times of the Day: Morning: Sign

Ireland

that immediate descendant of Paracelsus, Doctor Rock, is expatiating to an admiring audience on the never-failing virtues of his wonder-working medicines. One hand holds a bottle of his miraculous panacea, and the other supports a board, on which is the king’s arms, to indicate that his practice is sanctioned by royal letters patent. Two porringers and a spoon, placed on the bottom of an inverted basket, intimate that the woman seated near them is a vendor of rice-milk, which was at that time brought into the market every morning (217).

The Four Times of the Day: Morning: Sign

Lichtenberg

In the background stands the notorious French-pox doctor Rock with his notice-board and his little potions and lotions, advertising himself and his medicines, to those who have fallen for the temptations of the illness in which he deals. In spite of its being so early and cold, he already has an audience, among them a woman wearing a hood because of the cold and the onlookers. Doctor Rock is said to be a true likeness, in spite of being a portrait delineated with so few strokes. Hogarth is extraordinarily gracious towards this man; he uses every opportunity of recommending him to posterity. What can he have done for him? (280-281).