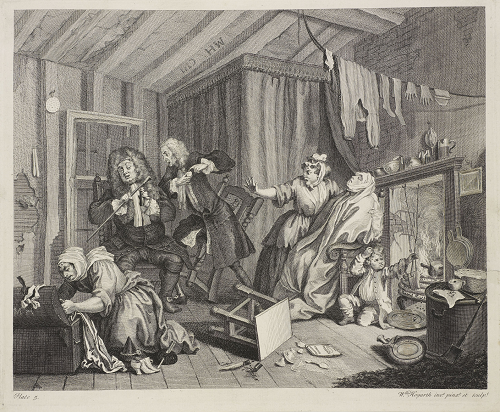

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 5

1732

11 7/8” X 14 3/4” (H X W)

View the full resolution plate here.

View the copper plate here.

Moll, used by clergy and her lovers, is here an instrument of the medical profession. This plate elucidates the doctors’ mistreatment of a patient for their own fame and fortune. Here, the dying Moll Hackabout is attended by two physicians. Although Peter Quennell identifies the corpulent one as Spot Ward (98), known for his wonder pill, most other commentators believe him to be Dr. Richard Rock, who also made a reputation for a cure-all known as the “famous, Anti-Venereal, Grand, Specifick Pill.” This identification is supported by a prescription signed by Rock, held in place by Moll’s teeth, compromised by her mercury cure. Rock is also pictured setting up shop in “Morning.” The other physician is consistently identified as Dr. Jean Misaubin, another pill doctor and the object of Fielding’s scalding wit. He dedicated The Mock Doctor to Misaubin and writes in Tom Jones that the doctor was so confident of his reputation that he “used to say that the proper direction to him was “To Dr. Misaubin, in the World.” Hogarth also uses Misaubin as his quack doctor in Marriage à la Mode. Moll’s naiveté has also led her to invest in the anodyne necklace, the advertisement for which appears on the floor.

Ireland and Nichols comment that each of the physicians is accusing the other of poisoning Moll (115); however it does not appear that they are concerned with her at all. Neither doctor even looks at his patient, and their violent quarrel over the effectiveness of their respective cures, disrupts tables and chairs, continuing despite Moll's attendant who pleads with them to either cease their dispute and honor the solemnity of the occasion or attempts to attract their attention to the suffering patient. Their fine dress contrasts with Moll's attire—a sheet used for sweating cures—and with her impoverished surroundings which imply that much of Moll's money has been spent on her ineffective cures. Misaubin literally has his back to the patient, a pose that many of Moll's potential benefactors have adopted. Most notably, is a parson striking the same pose in the initial plate of the series, setting the tone of neglect that will follow Moll through her life. Her tragedy could have been prevented, or at least lessened, if the clergyman had been less concerned with his letter, likely soliciting a position from its addressee—the Bishop of London. He, like the doctors of Plate 5, is more occupied with his own advancement than with the obligations inherent in a life of service. Hogarth, then, indicts them all. An additional level of irony is that the one figure consistently devoted to Moll is her noseless, syphilitic servant who demonstrates more humanity than those dedicated to its improvement.

This plate also reveals that Moll has a child who will serve as part of the legacy of her downfall. Despite being infested with vermin, he is healthy, having clearly never missed a meal. Moll’s motherhood is ambiguously depicted; he is certainly well fed but is also clearly fending for himself. Unlike the Squanderfield child in Marriage à la Mode, this young boy shows no sign of the syphilis which killed his mother and has almost certainly infected him. Shesgreen notes that the scene is “agitated and disordered” but the disorder is very much confined to the room (22). Also important is the lack of artwork on the walls—Hogarth often uses additional works to magnify the symbolic import of his scenes. Here the walls are almost bare, save a broken mirror, which, rather than opening the plate to a more cosmic significance, makes it a more individual fall.

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 5

Shesgreen, Sean. Engravings by Hogarth. (1973)

Moll is dying of venereal disease; already her face is white and waxen and her head falls lifelessly backward. The scene around her is agitated and disordered. Two expensively dressed parasites (identified as Dr. Richard Rock and Dr. Jean Misaubin) quarrel violently over the efficacy of their cures as their patient-victim expired unattended in their view. Before Moll’s corpse is cold, a strange woman (perhaps her landlady) rifles her trunk. She has already selected for herself the most ominous articles of Moll’s wardrobe: her witch’s hat, her dancing shoes and her mask (now a black death mask) with a fan sticking grotesquely through its eyes. Moll’s maid, with one comforting arm around the dying girl, attempts to stop the looting and the turmoil. The girl’s son sits beside his mother, oblivious to her death, struggling with the lice in his hair and attempting to cook for himself.

The small apartment is the poorest and most primitive of Moll’s abodes. Plaster has fallen from the walls; coal is staked to the right f the fireside net to the bedpan covered with the plate (“B. . . Cook at the . . .”); holes in the door have been filled in to keep the place warm. The room is without any of the signs of Moll’s personality that characterize her previous apartments. Instead of works of art there hang on the wall only a broken mirror and a fly trap (a Jewish Passover cake coated with a sticky substance).

Nor are there any of the usual signs of liquor; all her money has been spent on quack cures for her disease. On the floor, by the overturned table, lies an advertisement for an “anodyne” (pain-killing) necklace purchased to cure her or perhaps her son’s congenital syphilis. The mantelpiece is lined with similarly useless prescriptions. By the pipe, spittoon and old punchbowl, lie Moll’s teeth; loosened by the fruitless use of mercury as a cure for venereal disease, they have come out. Over the expiring figure of Moll hang the limp, ghostly forms of her laundry (22).

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 5

Uglow, Jenny. Hogarth: A Life and a World. (1997)

The next room, Moll's sick room, is even barer. Both Justice and Nature have punished her. The law sent her to Bridewell, and disease sentences her to death. The rich bed-hangings of the second plate are replaced by a pathetic line of washing, the pictures on the walls by obscure obscenities on the ceiling and crude objects, diagram-like parodies of female and male: the round cake of 'Jew's bread'--a perforated Passover biscuit, used as a flytrap--and two limp sheaths. In the middle of the scene two quacks argue violently, sending chair and table crashing to the ground, one being the fat Dr Rock, inventor of the 'famous, Anti-Venereal, Grand, Specifick Pill' and the other the thin Dr. Jean Misaubin, creator of a rival cure. Ignoring them, a tough-faced woman rifles the little trunk that once stood by the hopeful girl in Bell's Inn Yard and Moll’s small son scratches his head over the meat as the pot boils over. On the floor, among smashed pottery and spilt ink, a paper advertises the ‘Practical Scheme Anodyne Necklace’, which was both a universal panacea for everything from croup to syphilis and a slang name for the noose. Amid this turbulence and noise, the crashing and shouting, the hissing water and raging fire Moll’s life is seeping from her. She has no strength, no bite. She has been suffering the cure of ‘salivation’, wrapped in blankets to make her sweat the disease away, dosed with mercury that makes her gums swell and her teeth fall out--they lie to one side on a crumpled paper marked ‘Dr Rock’. She looks like a huge silent insect in a chrysalis, a shapeless bundle supported by her horrified old maid in a grim burlesque of the death of the Virgin.

Some commentators felt that the series should end here, with Moll's death, the wages of her sin. But Hogarth’s bitter comedy insists that life goes on (207-209).

One sign of Hogarth’s respect and compassion toward Moll in A Harlot’s Progress was in showing that she kept her child alive, and even when she herself was dying in squalor her boy was fed and stoutly clothed. Many were not treated so, especially the illegitimate (326).

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 5

Paulson, Ronald. Hogarth’s Graphic Works. (1965)

If Plates 2 and 3 constrast the false gentility and the ugly reality of the Harlot’s life Plates 4 and 5 parallel her two relentless pursuers: law and disease, in Bridewell and now in the sick room. (As introduced in Plate 3 by the entrance of Gonson, so the other was hunted at by the nostrums kept near the Harlot’s bed.) The two doctors in consultation were well-known for their quack cures for venereal disease. The fat one in the full-bottomed wig is identified by the added inscription on the paper holding the teeth ("Dr Rock") in state (3) as Dr. Richard Rock, “The famous Anti-Venereal, Grand, Specifick Pill,” advertised in the Craftsman (Feb. 24, 1732/3; see also Morning). Rock (1690-1777) was also described in similar terms by Goldsmith in The Citizen of the World (1762), Letter 68. The lean doctor is probably intended for Dr. Jean Misaubin (d. 1734), inventor of another famous pull for prophylaxis and venereal disease (Biog. Anecd., 1782, p.163; J. Ireland, I, 17n., 3,328; cf. the portrait-sketch by Watteau, etched by A. Pond in 1739 as Prenez des Pilules, BM Sat. 1987, and Hogarth’s Marriage à la Mode, Pl.3). Fielding satirized him about this time in The Mock Doctor, which opened June 23, 1732.

While the doctors are quarreling over the merits of their respective cures, Moll Hackabout is expiring, wrapped up in “sweating” blankets. The teeth on Dr. Rock’s paper are Moll’s, loosened by the use of mercury (the “salivation” for syphilis. Her old portmanteau us here, with “MH” on its top, a grim parallel to the “MH” smoked on the ceiling; it now contains her mask, her witch’s hat, and other masquerade attire (from Pls. 2 and 3). The woman who has come to prepare the corpse is going through the trunk in an effort to find some decent grave clothes—but all she finds are costumes, which she will doubtless claim as her own perquisites. Moll still has the noseless servant woman with her (Pls. 3 and 4); and the little boy, concerned only to get some supper, and scratch his lousy head, is clearly hers. The piece of “Jew’s-bread” hanging on the wall by the door, which was used as a flytrap, reminds us of her Jewish admirer (Pl. 2). The bedpan in the right foreground is covered with a plate engraved with the name of the owner, "B ... Cook at the ..."

The paper with "PRACTICAL SCHEME" and, with reversed "Ns," "ANODYNE [Necklace]" and a pictured necklace, refers to a much-advertised panacea of the time. 'Hogarth has ironically combined the two uses of anodyne necklaces (which were advertised in newspapers daily during these years, with the little design on the necklace and a child's head): as cures for the pains and complications of teething and for venereal disease. A typical advertisement (Craftsman, Dec. 2, 1732) claims curative power "for Children's Teeth, Fits, Fevers, Convulsions, &c. and the great Specifick Remedy for the Secret Disease." Rock too had a much-advertised toothache cure ("without drawing") as well as his "famous, anti-venereal, grand, specifick pill," and they were often advertised in parallel columns. Thus the teeth lying on the paper refer to both the little boy and Moll. The necklace can suggest that (as Marjorie Bowen believes, p. 139) Moll "has at least had that one tender thought for her child," that she is simply trying another cure for her own disease, or, as in Marriage à la Mode, Pl. 6, that she may be treating signs of her own disease in the child (148).

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 5

Paulson, Ronald. Hogarth: His Life, Art and Times. (1971)

Thus the Harlot suffers from lack of attention by supposedly humanitarian professional men. In Plate 5, she is ignored by doctors (vol. 1 253).

The two quarreling doctors in Plate 5 offer the basic choice of bottle or pill. Most are bottle cures—the “Anti-Syphilicon,” 6s a pot, and the “Diuretic Elixir” for “Gleets and Weaknesses,” 5s a bottle. Another was Dr. Rock’s “incomparable Electuary.” “the only VENEREAL ANTIDOTE,” 6s a pot, sold at the Hand and Face near Blackfriars Stairs; Hogarth inserts Rock’s name in his revised plate of 1743. As to pills, Misaubin’s famous brand (which however does not appear advertised in the papers until a later time) there were “the famous Montpelier little BOLUS . . . so immediate a Cure, That of those Numbers that daily take it, not one fails of having the Infection carried off by 1,2,3,or 4 of them, as the Distemper is more, or less upon the Person”; or “the long experienc’d Venereal little Chymical BOLUS”; or the “famous Italian Bolus.” Hogarth’s pill doctor, according to contemporary report, was a portrait of the French empiric, Dr. Misaubin, who also appeared frequently in the papers; typically in December 1730, Misaubin, “in St. Martin’s-Lane, gave a magnificent Entertainment to several Noblemen of Gentlemen, in which Company was Sir Robert Flagg, Bart. Of Sussex.”

The other cure, besides the sweating treatment in the Harlot’s room is the Anodyne Necklace. Its advertisements, which ran for decades in nearly every newspaper, derived from a shop at the Sign of the Anodyne Necklace, against Devereux Court outside Temple Bar, where two distinct remedies were sold: the necklace for teething children and for venereal disease. Thus the presence of the necklace could refer to the son or the mother or both. Judging only by the venereal disease ads, a reader might well conclude that the disease rate had appreciably increased and was parallel to those degeneracies Pope chronicled in The Dunciad, where indeed the parallel is suggested in Curll, the allegedly syphilitic bookseller. And this must be taken as part of the commentary of Hogarth’s fifth plate, with its doctors and variety of cures coupled with the image of death and degeneration (vol. 1 254-255).

. . .in the fifth plate, as the consequences overwhelm her, though dying of syphilis she has in attendance two doctors who are quarreling over their respectable fashionable cures; her gowns and masquerade costumes are still in sight, though being rifled in anticipation of her death (vol. 1 257).

Plate 5 resembles various deaths of the Virgin (vol. 1 270).

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 5

Ireland, John and John Nichols. Hogarth’s Works. (1883)

Released from Bridewell, we now see this victim to her own indiscretion breathe her last sad sigh, and expire in all the extremity of penury and wretchedness. The two quacks, whose injudicious treatment has probably accelerated her death, are vociferously supporting the infallibility of their respective medicines, and each charging the other with having poisoned her (The meagre figure is a portrait of Dr. Misaubin, a foreigner, at that time in considerable practice). While the maid-servant is entreating them to cease quarrelling, and assist her dying mistress, the nurse plunders her trunk of the few poor remains of former grandeur. Her little boy turning a scanty remnant of meat hung to roast by a string; the linen hanging to dry; the coals deposited in a corner; the candles, bellow, and gridiron hung upon nails; the furniture of the room, and indeed every accompaniment, exhibit a dreary display of poverty and wretchedness. Over the candles hangs a cake of Jew’s bread, once perhaps the property of her Levitical lover, and now used as a fly-trap. The initials of her name, M.H., are smoked upon the ceiling as a kind of memento mori to the next inhabitant. On the floor lies a paper inscribed ANODYNE NECKLACE, at that time deemed a sort of CHARM against the disorders incident to the children; and near the fire, a tobacco-pipe and paper of pills.

A picture of general, and, at this awful moment, indecent confusion, is admirably represented. The noise of two enraged quacks disputing in bad English, the harsh vulgar scream of the maid-servant, the table falling, and the pot boiling over, must produce a combination of sounds dreadful and dissonant to the ear. In this pitiable situation, without a friend to close her dying eyes or soften her sufferings by a tributary tear,-- forlorn, destitute, and deserted,--the heroine of this eventful history expires; her premature death brought on by a licentious life, seven years of which has been devoted to debauchery and dissipation, and attended by consequent infamy, misery, and disease. The whole story affords a valuable lesson to the young and inexperienced, and proves this great, this important truth, that A DEVIATION FROM VIRTUE IS A DEPARTURE FROM HAPPINESS.

The emasculated appearance of the dying figure, the boy’s thoughtless inattention, and the rapacious, unfeeling eagerness of the old nurse, are naturally and forcibly delineated.

The figures are well grouped; the curtain gives depth, and forms a good background to the doctor’s head; the light is judiciously distributed, and each accompaniment is highly appropriate (114-117).

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 5

Quennell, Peter. Hogarth’s Progress. (1955)

At length, we assume, she is released [from Bridewell, see Plate IV]; but, between that moment and the opening of the next scene, some four or five years have evidently elapsed since she has given birth to a little boy who shares his mother’s sick-room. Squatting on the hearth, he scratches his head and, with the other hand, does he best to roast a scrap of butcher’s meat. The room is crowded and hot and noisy. Yet more implacable than the relentless Sir John, syphilis, occupational disease of her class, has pursued Moll Hackabout from her Drury Lane attic, its window-ledge already ranged with significant jars and medicine-bottles, to the bare lodging in which she has now taken refuge, probably in the same disreputable and insalubrious neighbourhood. Two doctors are arguing her case, one of whom was recognised by Hogarth’s contemporaries as Dr. John Misaubin, quack-specialist in venereal diseases and inventor and purveyor of a well-known prophylactic pill. Dr. Ward (Ward’s Pill is mentioned in Tom Jones, where it is described as “flying at once to the Part of the body on which you desire to operate.”), his companion, has also a specific ready; for this was a period when English medicine, despite the rapid advance of scientific knowledge, was still in a confused and daringly experimental stage, and almost every renowned physician had evolved and given his name to some mysterious private concoction—his powder, elixir or drop, reputed to relieve the symptoms of several different illnesses. So the pill-mongers have hot into a noisy dispute; and, while Misaubin bullies and scolds, his plump colleague appears to be waving him away with the gold-headed cane he is carrying as his wand of office. That cane was the doctor’s badge, its gold knob being raised to the lips and gravely gnawed or nuzzled at, as he bowed over the patient’s bed and prepared to announce his considered opinion. By no opinion or remedy can they hope to save Moll Hackabout. Mercury-treatment, or salivation, has been tried without success; the advertisements of an “Anodyne Necklace” lies discarded on the naked boards, beside a heap of coals, a shovel, a chafing-dish and a broken plate. Moll’s agony, propped up in an armchair, is observed by her faithful charwoman. The little boy is twirling his lump of meat: the nurse rummages in an old-fashioned trunk—the very trunk, stamped with the brass-headed nails, that once accompanied Moll to London during her journey on the York Waggon (98-99).

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 5

Lichtenberg, G. Ch. Lichtenberg’s Commentaries on Hogarth’s Engravings. (1784-1796). Translated from the German by Innes and Gustav Herdan (1966)

Here we have the transition to the last fermentation—she dies, and from the terrible consequences of pandemonial love. We should be grossly mistaking the intention of our great artist if we were to mince words here, provided we need use words at all. For it is hardly necessary. Everything speaks for itself. From the pale cheek and stiffened lips death has effaced the smallest trace of wanton charm, which art had erstwhile added from without or within. Closed for ever is the mouth from which, but a few months ago, flatteries or mild imprecations used to fly with double-tongued volubility at the passer-by, according to whether he fought weakly or strongly against its wiles; for ever extinguished is the eye that shot its glances around full of affected fire, less for the purpose of seeing than of being seen—and now it sees no longer, nor is seen. At this complete evaporation of all her cheap glitter in the sight of Death, she comes before him in the simple garment of her first naturally-good disposition, and implores his pity. She did not find it. Yet we would not wish to deny her ours—Quiescat!

She sinks back death-pale into the comforting arms of the woman who had hitherto the care of her soul, and was her faithful companion in the House of Correction, the abominable snub-nose who now suddenly loses all hope of leading her lovely ward, had she only lived and flourished longer to her own advantage, to the gallows. That is comfort indeed! She has been carefully wrapped up in a sheet. Perhaps the nightgown which is hanging on the line there to dry is her only one, and through the rapid change made necessary by nature and art, is still out of action! With her right hand the creature enjoins peace and silence upon the two respectable gentlemen engaged in confidential discussion. Who these two men are we shall now explain. The matter is important, and the reader will therefore grant us a little space for it.

In London there has appeared for many years now a weekly periodical which is turned out regularly, and always contains articles of more uniform quality than any other weekly paper in the world. It has never lacked contributors or contributions. Everything it contains appears to have been dictated by Nature herself, although one knows that it was often profound human skill which guided the pen. This is not to be wondered at; it is even an observation apparent to anyone who understands human nature. For since a certain happening in Paradise, about which we may read in an old classical book that is not very much read nowadays, man has been so much thrown upon the left side of his nature that it has been a proper study to regain his right. Perfect order reigns on every page; everything has its appointed place here, so that the lover of such things may immediately find his way about. It is particularly strong in the touching, and the pathetic. Passages which cause the reader's tears to flow, and others where his whole being is shaken by shudders, are far from rare. These pages bear the heading: 'Weekly Bills of Mortality'. This little introduction was necessary before informing my reader that the two gentlemen he sees there are a pair of learned men who at that time were specially engaged in procuring for that journal the utmost completeness. They were, in every sense of the words, for this weekly paper what the famous Addison and Steele were for another, to wit the well known Spectator. Without them it could not have carried on with such completeness. So much is certain. But on account of the great number of collaborators, each of whom had his friends who wished to procure for him the distinction of being considered by Hogarth as deserving eternal remembrance, the names of these honest men are not known for certain. This much is evident, that they are a pair of Officiers de Sante (Medical Officers) as doctors are now called in the Paradise of Europe (Paris of the Revolution), and, as we have reason to believe, have about the rank of prison warders. For apart from these persons, and occasionally some respectable experimentalist or elderly matron, nobody was allowed to supply contributions to that weekly journal. Now according to a reliable tradition, the rather corporeal gentleman with the convex belly is thought to be a German, the other more spiritual one with the concave belly a Frenchman named Misaubin. Of their manner of life, only a few trivial items are known, and are hardly worth mentioning. The first, so it is said, for some time played the clown with Fargatsch of Hamburg; from there he fled to London to evade prosecution for having prepared a tooth-powder from human skulls; for a while he practised there for dear life, and was ultimately hanged. People say it was for murder. If so, it was probably not a professional one, for it is well known that doctors in England enjoy the privileges purgandi, saignandi et tuendi as much as anywhere else. Thus there remain only two possibilitites: either he was hanged for his professional sins because he was not a proper member of the profession, thus not a doctor proper but a mere lusus naturae; or he killed the person by a contrivance which was not a legitimate one. Ten or eleven years ago a famous London doctor, Dr Mr Gennis, almost ended on the gallows in that way (he was condemned to be hanged but was later reprieved). He had done no more than bring his landlord to the churchyard. They only came down on him so heavily because he had done it without the agency of a mixture or powder, but merely with a breadknife which he had sunk in the patient's body, and in this way had by-passed, as it were, the apothecary. The other figure, Dr Misaubin, was quite a good man, only he had rather too high an opinion of a certain powder and certain pills which he compounded in his own establishment; the latter being a sort of edible deer-shot. If death approached one of his customers, very well—he loaded the patient with the pills as if with grapeshot, and fired. In this way he skirmished and fought many a year with all possible diseases. Official reports of his victories are not available, but quite considerable loss of heavy and light cannon could regularly be traced in the weekly journal. I have heard that out of malice (when is that ever absent from merit?), they gave the honest man the nickname of Mice-Aubin. This was because in later years, when another would perhaps have rested lazily on his laurels, the good fellow tried his art on rats and mice. It is a bitter and bread-depriving name, and that means quite a lot to a poor devil who even without it had the embonpoint of a rat d'eglise. Highly unjust are such rat-like attacks upon the larders of one's fellow-men. And had he really behaved so badly? He could no longer visit patients but still had a good stock of his little powders; he therefore tried them out on whatever came to his surgery. Oh! this is often the way of the world! How much good gunpowder and shot intended for partridge and snipe are used up on the way home upon sparrows and bats, whether out of boredom or to show one's skill, or because nothing better is available. And after all, is the pursuit of vermin so very far outside the scope of medicine? What then are lice, tape-worms and maw-worms and the Greek trichuriden? Every occupation has its gradations. I am therefore convinced that the ingenious author of Gil Bias, in speaking of the exécution de la haute medecine, had a distinction of this sort in mind, something like game-shooting and rat-catching.

So much for the history of these famous men, and now for the use to which our artist has put it. The girl has fallen a victim to them, and how else could such a duel have ended? She fought against death and had none for Second but her own natural constitution, good in itself but often injured, weary, and neglected at every opportunity. And yet, perhaps, being a young woman of 23, she might still have beaten her adversary. But He who knew this well had chosen for himself a pair of Seconds, each of whom could have taken up the fight alone against a dozen lives. That is why it went veni, vidi, vici, and suddenly there she lay. That this is the true explanation of the matter is all too evident. For if the toad and the salamander who are quarrelling here had not been Death's malicious Seconds, but had taken the side of Nature, they would even now be striving to resuscitate the girl, whereas they are leaving that to—the last Trump, and merely quarrel about who is to have the honour of the deed. This mixture of mine in this glass, says the toad, was the true oil on the fire; and my fire, shrieks the salamander, had no need of your mixture. What a conflictus pronominum! ‘I’ against ‘I’ and 'you' against you'. These are hard blows, especially those of the ‘I’s. And how beautifully they are demonstrated here, entirely in keeping with the laws of impact. The ‘I’ of the German has little velocity but all the more mass, and consequently has impulse even when it seems to be at rest; the ‘I’ of the Frenchman, on the other hand, has velocity but little mass, and therefore it felt the need of support from tables and chairs and whatever else came in handy. How gratifying for a German to observe how by the forceful thrust of his countryman, the French mass, which had only been pieced together, falls apart in all directions! Chair and table and plate and spoon and ink bottle everything separates from the tiny kernel and collapses at the impact of the other's quiet remark: "this is my little mixture', while his chair stands at rest, as it always has and always will.

But there is still more to this group. It is of inexhaustible significance. Would it be possible, one might ask, to depict a congress of diseases, or what comes to the same thing, of quacks, more eloquently than here with this dropsical individual and this hectic one? The one inflated, heavy, phlegmatic and stolid, the other concave-bellied, feverish, mobile and skinny? How Dropsy squats there! Medicine bottle and cane gripped as if they were the insignia of his blood-brother—hour-glass and scythe; Hectic, on the other hand, having surrendered scythe and hour-glass to his colleague, retains for himself the skeleton shape and the deadly powder in the pill box, which proclaims better than all the hour-glasses of his friend that the hour has struck—the rat powder. The eyebrows of each reach up towards the adjacent hair, the wigs, with a sort of longing which, they say, tends to signify inner conviction combined with a touch of righteous anger over a failure to impress. Here, however, especially with the dropsical subject, these hair curves come rather too near to one another, nearer than with his hectic companion, and this rather detracts from this interpretation. If I am not mistaken, such an elevation of the brow signifies rather a consciousness of uncertainty which tries to hide under the mask of caution. With Dropsy it seems to have been brought on by mental conflict due to undigested reading; in the more determined eye of Hectic we seem to read the effects of physical indigestion. 'Oh dear, dear sister,' protests the former, 'do believe my word!' 'No! rubbish, rubbish, absolute rubbish!' gasps the latter. 'Here in this pill- box. . .' and from this explosion in front the recoil is so strong, as with guns in general, that chair and table collapse. This, as the reader will observe, is a second hypothesis to explain the revolution in that room. We intentionally put it side by side with the other which sought to explain everything by a blow from the German, and it will find favour with those who believe that if only the German can maintain his phlegmatic attitude long enough, his opponent from the volcanic nation would burst of his own accord, or disperse into his constituent parts. But by no means, dear reader, considering the limitations of our individual vocabulary, and our lack of knowledge of the world, would we attempt to express in words alone the constant and quietly operating forces, as well as the erratic and turbulent ones, which were at work here, together with the vociferous interference by snub-nose with her wormwood face, or to try to represent completely in the form of an idyll what Hogarth has so inimitably delineated with his stylus.

The explosion has overturned the little table and with it a spoon, a plate, an ink-bottle and pen, and a bulletin. The spoon has come off quite well, it lies on its hollow side and touches the clean floor as little as possible, thus differing from bread and butter, which always falls on the buttered side. But the plate!

Broken, broken is the lovely jar, there lie the fragments! (Gessner, Idylls)

This is a sad thing for a whole plate, but not quite so serious for a damaged one. From the visible fragments, at least, it would not be possible to piece together a plate capable of containing anything which the neighbouring paper poster could not hold equally well. The ink-bottle breaks and the earth receives in a wholesale way the black gall with which it was filled, and which as an ingredient of prescriptions and love-letters may perhaps have led many a poor devil to that very consummation. It has finished its service. The collar round the neck of the pen, which has saved it from ruin, protects it at least from further destruction, and even if it were trodden upon in the turmoil, which however will not amount to much in this comer, there is still another department where it could find employment. Isn't it a splendid thing to have apart from one's writing end also a wiping end? If as a writer you are no longer able to give instruction, stilum vertas! and you can still sweep. A moral which every budding author who has invested his spiritual and physical fortune in disastrous South Sea shares of wealth and immortality through writing should let his dry pen teach him every morning, before he dips it into the ink bottle to preach with it his revelations to the world. The poster advertises a practical scheme concerning a new method for curing all kinds of diseases by neckbands or necklaces. We can see an illustration there of the necklace in question. At the top is the word 'Anodyne' written from right to left, and below from left to right the word 'Necklaces', which even in the original is difficult to read. The lines are meant to curve rather in the form of a neckband, for they really make a circumscription, a sort of band around the neckband, and perform here in reality for the project the service which the project itself merely promises to the patient. Thus 'Anodyne Necklaces', necklaces which are to take away pain A circle of words, half Greek and thus half mystical, drawn round an entirely mystical amulet, could not fail of its purpose with a certain class of person. It is really incredible, the success that device has achieved—I mean the outer band around the inner one. For whether the inner one had benefited the patient himself has not, as far as we know, become public knowledge, if we except the wall mentioned below. However, that poster does not lie here simply as a satire upon the innumerable advertisements for medicines which in London are daily thrust unstamped into people's hands, and even into their pockets, by some kind of postman; its meaning lies much deeper. This is one proof out of many which we shall come across that Hogarth in his works, just as Nature in hers, knew how to achieve, often with one and the same touch, more than one end, and knew also how to spread warmth where one might have thought he only wanted to shine. For these anodyne necklaces were originally intended by their inventor only for the use of children suffering from the so-called English disease (the Rickets), about which the unfounded prejudice prevailed in England and in many parts of Germany that it is usually the fruit of tainted love. This, therefore, refers to the poor little bastard who near the fireplace there half kneels and half sits beside the chair of his dying mother, and who, untouched by that dying and by the learned bellowing of the disputing gentlemen, and by the screaming intervention of the woman who presides over all this, quite peacefully roasts over the fire his pain- alleviating chop. Considering that he may be suffering from rickets, he could from his size be about six years old; deducting these six years from the mother's twenty-three, brings her age when she was infected to seventeen. This is what Hogarth tells us by means of a slip of paper which lies there between the fragments of a twice-broken plate and some pieces of furniture of rather equivocal form. If the stout gentleman on the up- right chair there were to have been the inventor of these pain-alleviating necklaces, as he could well have been, the satire would acquire more branches still. For, as we remarked above, our learned doctor himself died through an anodyne necklace, the rope (laqueus anodymus), which the law prescribed for him, and which in London works wonders.

Diagonally opposite, in excellent contrast with the death scene, is a little scene of acquisition. At least there is certainly a good deal of grasping going on there. An old woman, perhaps formerly a sort of chaperone to the girl, or else a relation of hers and of the smiling heir, or what is most likely, her present landlady to whom something is probably owing for rent and expenses, is now securing possession of the girl's little all, or at least she is reckoning it up, for the sake other peace of mind. The death rattle, the snorting and snarling of the doctors' fight, even the hissing of the pot boiling over, do not distract her; she knows that people are mortal, and that doctors will quarrel, and even that for the refilling of a pot which has boiled itself dry, nothing in the world serves better than the appropriation of a full trunk. A face like that is very necessary if in such a den of murderers one is not to make mistakes in calculation; it is the very image of deafness on principle.

There is something about the contrast between what the woman is pulling out here and what corruption is appropriating over there in the armchair which, as every man of feeling will recognize, rises far higher than Hogarth's genius usually aspired, but which, notwithstanding, has been as adroitly executed as if it had been entirely within his natural reach. Here lies first the dark negro mask with which the friendly, sunny, Yorkshire face had darkened itself for a while at a Ball with artificial ugliness, so as to dazzle by contrast a chosen few in a tête-à-tête with all the charm of bought favours. The fan, since the fire of glances has ceased, sleeps quietly in the embrasures, and perhaps mysteriously leads many an imagination to attributes of the Tragic Muse, even through the mummery of love. Next to it stand quietly the dancing shoes, whose form and movement and gold and twinkling and glitter like so many will-o'-the-wisps, used once to throw caution itself, the pedometer, into confusion, and lead on to where retreat was no longer possible. Behind them lies the hat which we have seen before in the third Plate hanging under the bed canopy, below the comet. Ribbon and domino are unpacked too. Were we to cover the whole Plate except for that comer, should we not think that an old chaperone was employed in gathering together a costume for today's Masked Ball, for the little lamb in her charge? But now remove the cover and cast a glance at the picture of misery there in the armchair, the former owner of all that finery! Heavens above! Her present domino, how limp, how pallid and how still compared with the rustling silk which billows from the trunk. Her present mask alas! how pale, the make-up provided by the cold hand of death! And the dazzling light other eyes, how deeply sunk into eternal night! They see not and are seen no longer! There is no mummery here. Those eyes in the wan face have really been pierced by the solemn arrow of death. With the black mask of luxury over there it was a dagger fully congenial with those eyes, a closed fan, not dissimilar in form as well as in use to the sword, I mean the rattle of—Harlequin. And where now are the little will-o'-the-wisp feet? Answer: the lithe, hopping red-breast needed them for her living on the thorny lust-hedges of Drury Lane; the heavily draped Bird of Paradise there upon the arm- chair no longer wants them.

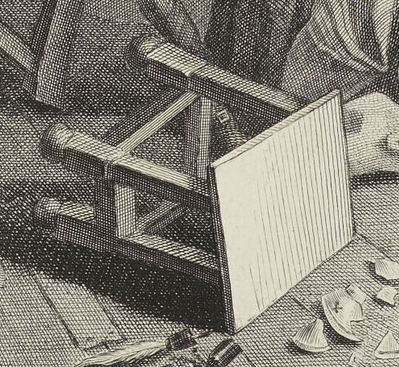

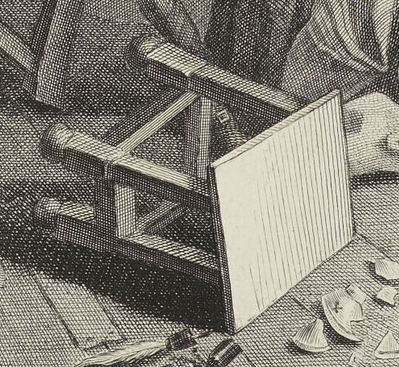

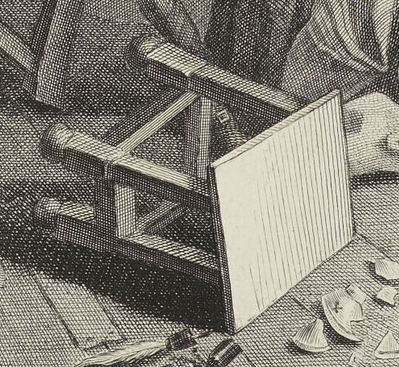

Just as we have drawn a line of comparison from the chair of the candidate for corruption to the travelling trunk, so we could draw another between the candidate for the gallows and another trunk that stands in the right foreground. Of course, the latter is more a chair than a coffer, or just as much (or rather more) a coffer to sit upon as a chair to shut something in. It is partly covered, partly surrounded by all sorts of trivial articles of which alas! shovel and coal are by far the cleanest Oh we were always afraid of that comer in the fifth Plate! If, however, we succeed in bringing our readers safely out of it, there remains but one other in the sixth Plate, before which we are already trembling. We confess this m advance, not only frankly but even not quite without a beneficial intention for ourselves, at least. For if someone has made up his mind to a rather disagreeable task, not entirely without persuasion and not altogether of his own free will, nothing exculpates a possible human faux pas so well as an open-hearted confession in advance: that one is in fact very apprehensive of not getting through without some unpleasantness.

Not to leave the subject too abruptly, which is sometimes dangerous and would be specially so here, we must first send a few remarks in advance, for one of which the reader will be just as ready to let us off without proof as we shall be pleased to give it for the other The first is that every freeborn human being, even one who is not censor-free has a natural right to say what he likes about chairs of all sorts, as long as he leaves in peace the people who honour them with their behinds And the second, that there simply does not exist in the world an utterly contemptible type of stool. The last sentence is especially important for us In order to persuade people of it one need only bring the matter near enough to the ancestor- and family-sense with which nature has endowed everybody so conscientiously that almost as much enlightenment is needed not to honour an otherwise unimportant man of family as not to worship the sun. So here goes.

In the whole realm of furniture which, to the best of my knowledge has not yet found its Linnaeus, the class of chairs (classis sellarum) is not only the most revered but also the most extensive; it is a class which not only flourishes at all points of the compass, but has discovered how to make itself indispensable. In a word, it is among furniture what the class of mammals is among everything that lives and feels. There are of course great differences between chair and chair, as regards form and weight' just as with mammals, for instance between the whale weighing more than many a house together with the inhabitants, and the Siberian shrew whose weight rarely comes to 30 grains. But as all these animals have as a common characteristic that they suckle their young, so all chairs have this m common, that when in service they are presented with quite a respect- able part of the body to support. To them belong, apart from ordinary stools and chairs with and without backs, and with and without arms, first all the thrones and all the cathedras from which, as is well known, the world is governed, and which, run into one by skilful carpenters, formerly represented what was called the Holy See. Next, all the Judges' chairs, the heavy chairs of sorrow to which some of the foremost thrones of the earth are said to belong, and the light bergères (armchairs) to which again belong many a throne and many a cathedra. After these comes the genus of benches, which are nothing but systems of chairs. Here belong the aristocratic and learned benches, all slaughter houses, the so-called lazy bench and the eternal long bench—the whale of the genus. These are followed by the Sedan chair and the Bath chair, the ivory sella curulis of ancient Rome, as well as the so-called chamber-chair between table and bed for those suffering from gout and rheumatism. In conjunction with this comes the cabriolet; the English storey-high phaeton whose name derives from 'turning over'; all flys, all carriages, all travelling and mail coaches from the German rib-shatterer to the English cradle on springs and the majestic State carriage for which, instead of making the gates wide and the doors high for it to pass through, they more modestly took first the measure of the doors and gates. Immediately next to the benches and opposite the Bath chairs comes the species of sliding chairs or the so- called sledges in hundred-fold form; from the magnificent structure which to the silver sound of a thousand bells overtakes even the wings of a winter Zephyr, to the mourning-sledge which to the simple sound of the tolling bell moves to the place of execution. Then come the riding saddles (also a genus sellarum), the men's as well as the lesser known feminine side-saddle, which nowadays the fleetest and proudest of all horses, Pegasus itself, no longer disdain. From another side, and stretching far into the distance, we have the Inquisition chairs of Holy Justice and the torture seats for the accouchement of confessions, and the medical-surgical chairs for achieving more substantial extractions. Of the latter type an extremely rare example is to be found in a museum at Rome, though I have forgotten its name. After a considerable interval comes at last the Désobligeant which is here under discussion, and which takes its name from the Goddess of the Night. 'Ah! quel bruit pour une omelette! Could you not have told us that at once?'—Impossible Madame. 'Why not? I would merely have said: with all due respect." And so more or less without any respect—No! what can be said only 'with due respect' must also be said respectfully, and that requirement we believe we have now fulfilled.

After this if not diplomatic, at least diplomatically circumstantial exposition of that seat's genealogical tree, and consequently of the proof that it is in its right setting, we now expect from our gentle readers a free passport for its companions. These comprise a small tin vessel with a handle and, immediately behind, a rather equivocal bowl, and on the ground a no less equivocal earthenware pan covered with a tin lid. The little vessel is clearly a Dutch spittoon (Quispedorje) and in more than one respect fits rather well into the suite. It is standing on an advertise- ment of the immortal Dr Rock. Can those be pills which are lying on it? Pills which lie between the name of Dr Rock and a spittoon are mercury pills all right. But the pipe? Perhaps it lies there only to mask the spitting, just as brandy drinkers of some standing and principle are said to drink brandy out of tea-cups to spare the feelings of their weaker brethren. Or is there perhaps such a thing as mercury-tobacco? Or was the last favoured lover perhaps a sailor from the land of cleanliness?

We have called the bowl up above and the pan down below equivocal; this they are in a very high degree. How if the first turned out to be a butter or dripping bowl and the other a frying pan which has just been lifted off the fire with a wet rag? That would be some evidence of orderliness, and also of precaution, namely that these chaperones had made some provision for themselves on such a day. In any case, somebody's goose is being cooked here. Perhaps death appeared suddenly after a happy expectation of complete recovery and they began too soon to think of feasting, for which pots and pans and bottle are as indispensable in England as drum and trumpet with us. On such occasions one offers thanks to Heaven, without forgetting oneself in the process. Everybody according to his customs—that is as it should be. But there may be another interpretation, which almost seems to be the right one, and that is precisely what makes that corner so—dangerous. What, one might ask, if the object which stands there behind the Quispedorje were something of the same type, only bigger, for instance an archi-quispedorje? And the pan down there a mere satellite of the worthy stool The assumption is somewhat strong but, according to our feeling, so much in Hogarth's spirit that we cannot possibly withhold it from our readers, especially as we have made such a profound apology. Besides, it is only the suite which is under discussion.

We mentioned above a line of comparison which might be drawn from the gallows-bird Quack and his consort to the corner under suspicion. The reasons for the comparison are these. Everything has been done to save the patient, but in vain. But in the hour of death both doctors hit upon an idea which might have saved her, had they thought of it sooner, and that is the medicines which they hold in their hands. Of course, each counts the other's medicine among those which could never be given too late. Both bottle and box, with the new medicines, are still unopened, and therefore the patient died. But where are the old medicines with their consequences? They lie partly in the armchair beside the fireplace, and then—in the corner under suspicion. In a word, that corner contains in various forms, the products into which those medicines were transformed. One grasped what was nearest to hand and sought for help first here, then there, and as speed was necessary, the vessels had temporarily to be deprived of their function in the kitchen and were transferred to the department where the stool presides. Thus afterwards one knew at least obiter where one was. On the pan lies a plate on which we can distinctly read the word 'Cook'. Evidently it belonged to the neighbouring chop-house. We shall not disturb it.

To that corner also belongs the bladder of well-known form, which has found a nail to hang from above the mantlepiece between a couple of medicine bottles and a broken jar. This is the best position for display in the whole room. If I am not mistaken, Hogarth wanted to intimate through the intentional elevation of that instrument and by bringing into prominence the allied vessels that the doctors had specially adopted the vomit and lavage method. With this I would agree. If however his intention was to mock, he was very much in the wrong. Does he not know that this method is almost the only one whose efficiency, so to speak, could be demonstrated geometrically and even elegantly? That the girl has died of it, what difference does that make? Good Heavens! what could one not die of? Did not the postman Jablkowsky of Warsaw in January 1792 die from 300 oysters? Since that demonstration, which is really due to Dr Swift, a well-known physician for sick souls and sick governments, has not become general knowledge as far as we know, we shall give it here translated into our somewhat learned book language, whereas Swift expresses it so that a child could understand it, and that would not do. Since diseases, as everyone knows, are said to be nothing but reversions of the natural processes of some functions in the body, it is not even thinkable that they should be reversed again, that is brought back into the right direction, so long as the old disorderly habits of life continue which brought about the first reversal. This, it seems to us, is so clear that the proof requires nothing for completeness but a reference in brackets to a preceding paragraph, which however everybody will here find in his own head. But since, furthermore, all who fall ill have, up to the moment when this happens, eaten or ingested in dubio with their mouth, which we shall call A, and have effected the emission with the opposite end B, it is impossible that, rebus sic manentibus, the disorder should be halted and their health again restored. Again as clear as daylight. What then is to be done? The problem answers itself: one must start to eat with the end B, and transfer the emission to the end A, id est, to give lavage and to vomit. Nature hesitates, bethinks herself, turns round, and in this way everything ends as desired.

Now finally let us glance at the furniture in the room itself. The mirror seems to have been discarded since the truth which it told began to be somewhat troublesome, and to have been relegated to the corner next to the fireplace, which is not very accessible and by no means the spot in that rather composite room where one would choose to disrobe and admire oneself, at least it is no place for an Os sublime. It hangs, of course, next to the fireplace, if one starts from the chimney; if one starts elsewhere, it hangs differently, etc. On the mantelpiece, where the household gods usually find their place, there stand here, too, the present Penates of that happy family, together with some sacrificial bowls dedicated to the past ones. Those are merely symbolical, the three Parcae in the form of three medicine bottles with their necklaces, and then the Ibis with its famous beak in the shape of a bladder. Here should have stood the super domestic god, the mirror which never smiles more graciously on its priestesses than when the fire on his altar through their chaste cheeks and eyes full of devotion is sending up to him light and glow. Above the throne of these goddesses floats a canopy of damp, perhaps still dripping, washing which stretches over the seat of the dying and by its influence transforms that apparently warm place into a veritable sub Dio. The time and place of the drying, as well as the number of pieces which are to dry, testify to deep poverty. How wretched are the house- holds where these three points are among the family secrets. Where the shirt on the washing line has to pretend to the chaste invisibility which it rightly preserved on the body. There luxury at least is out of the question. The whole change of service is then usually a change of one with one, or one with none. The last object on the line on the right hand side seems to be something padded, which is only hanging there for the purpose of being aired; one cannot tell quite what it is nor how it keeps its balance; but in the original it is drawn more as if it covered a similar piece as its counterweight. Probably it served itself for the purpose of padding, and would then be an impostor.

Opposite the chimney-piece, high up on a nail beside the door, hangs a round disc, perforated or indented, whose meaning Nichols, in his Life of Hogarth, has correctly interpreted. It is a Jewish Easter cake, Mazzos as they are sometimes called, which English Jews (as in some parts of Germany) send to their customers, more as a symbol of a substitute than as a real substitute, and which therefore they tolerantly treat not as victuals but as hardly more than an emblem of food. In England, the righteous of the fourth social class make fly-traps out of them, evidently by covering them with some sticky substance or, at least, with something which would for some time keep the dried mucilage in suspension. Nichols has repeatedly seen them used like that by people of that class. Whether it was Hogarth's intention to point merely at the class habits of the person occupying that room, whose whole Christianity had been reduced to that noble remnant of a cheap contempt for Jewry, or whether, as seems more likely to me, the cake at the same time represents a remnant of the past splendour of the second Plate, we gladly leave to the reader's judgment. In any case, the little moon was sure to reflect much light on to the sick- bed and, as Hesperus, would shine powerfully into the dying woman's conscience, which in the eventide of life is said to be very receptive to such reflections. At the Bell Inn she was betrayed, and that was a misfortune! In the Portuguese temple towards which that star is pointing, she betrayed and sinned on her own account, and that was a crime. That in this room there must have been better and happier times than now, happier too than in the House of Correction, of that we find in controvertible evidence on the ceiling. Almost over the bed we read the well-known 'M.H.' written with a brand, the initials which we saw upon the trunk outside the Inn in the first Plate. That trunk is seen here again only somewhat aged. Such inscriptions, executed by some bel esprit who had to climb on table and chairs, are seldom made without a good amount of high spirits But this is not all. Behind this 'M.H.' stands another word which Hogarth has almost blotted out again, and thereby contributed not a little to its lasting memory. We shall not, of course, restore it but merely remark for the benefit of lovers of unreadable inscriptions that the Latin translation of it can be found in the third Satire of the first Book of Horace How salubrious and airy this little room must be, especially for a somewhat be-quacked patient, strikes the eye immediately. On one side the whitewash has peeled off-the wall, and on the other the wood-work is partly rotten. On the left side, under the two tallow candles, it looks almost as if the wall had been patched up with a foreign substance. The door it appears, owes its rigidity not to the usual firm frame into which the panels are fitted, but to a single cross-beam upon which the boards are nailed. The doors of pigsties usually have three such beams, either parallel or in the shape of a Z. This structure is also the source of considerable loop-holes for healthy air and comforting looks, and these have been patched and pasted over with much consideration for elegance. Considering moreover, the tender childlike sympathy with which the boy follows the fate of his mother, the silent despair with which the old woman seems that all is lost, throws herself upon her knees, the dull, albeit gentle look with which the female minister to souls is still seeking, but hardly expecting, help from the compassionate doctors—then Molly's fate becomes almost enviable, at least for some people; it seems to me as if I heard their:

Où peut-on être mieux qu'au sein de sa famille? (52-67).

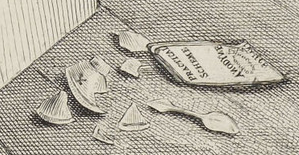

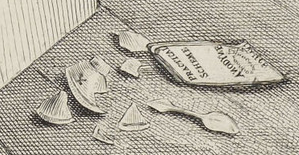

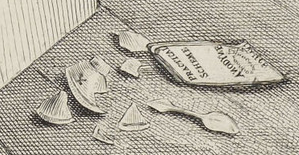

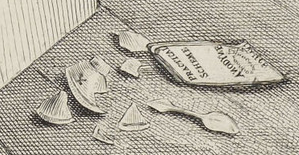

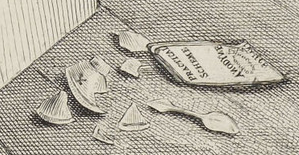

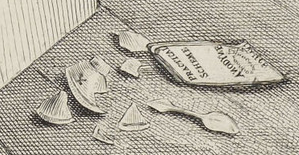

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 5: Broken China

View this detail in copper here.

Moll’s naiveté and desperation has also led her to invest in the anodyne necklace, the advertisement for which appears on the floor. The necklace, in addition to treating venereal disease was advertised to help cure children’s teething pains. Moll’s possession of this “cure” helps mitigate her immortality, as it demonstrates a likely concern for her child. However, Paulson notes that she may also be treating the boy for congenital syphilis, which makes the message ambigious (Graphic 148).

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 5: Broken China

Shesgreen

Nor are there any of the usual signs of liquor; all her money has been spent on quack cures for her disease. On the floor, by the overturned table, lies an advertisement for an “anodyne” (pain-killing) necklace purchased to cure her or perhaps her son’s congenital syphilis (22).

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 5: Broken China

Uglow

On the floor, among smashed pottery and spilt ink, a paper advertises the ‘Practical Scheme Anodyne Necklace’, which was both a universal panacea for everything from croup to syphilis and a slang name for the noose (208).

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 5: Broken China

Paulson, Hogarth's Graphic Works

The paper with "PRACTICAL SCHEME" and, with reversed "Ns," "ANODYNE [Necklace]" and a pictured necklace, refers to a much-advertised panacea of the time. 'Hogarth has ironically combined the two uses of anodyne necklaces (which were advertised in newspapers daily during these years, with the little design on the necklace and a child's head): as cures for the pains and complications of teething and for venereal disease. A typical advertisement (Craftsman, Dec. 2, 1732) claims curative power "for Children's Teeth, Fits, Fevers, Convulsions, &c. and the great Specifick Remedy for the Secret Disease." Rock too had a much-advertised toothache cure ("without drawing") as well as his "famous, anti-venereal, grand, specifick pill," and they were often advertised in parallel columns. Thus the teeth lying on the paper refer to both the little boy and Moll. The necklace can suggest that (as Marjorie Bowen believes, p. 139) Moll "has at least had that one tender thought for her child," that she is simply trying another cure for her own disease, or, as in Marriage à la Mode, Pl. 6, that she may be treating signs of her own disease in the child (148).

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 5: Broken China

Paulson, His Life, Art and Times

The other cure, besides the sweating treatment in the Harlot’s room is the Anodyne Necklace. Its advertisements, which ran for decades in nearly every newspaper, derived from a shop at the Sign of the Anodyne Necklace, against Devereux Court outside Temple Bar, where two distinct remedies were sold: the necklace for teething children and for venereal disease. Thus the presence of the necklace could refer to the son or the mother or both. Judging only by the venereal disease ads, a reader might well conclude that the disease rate had appreciably increased and was parallel to those degeneracies Pope chronicled in The Dunciad, where indeed the parallel is suggested in Curll, the allegedly syphilitic bookseller. And this must be taken as part of the commentary of Hogarth’s fifth plate, with its doctors and variety of cures coupled with the image of death and degeneration (vol. 1 254-255).

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 5: Broken China

Ireland

On the floor lies a paper inscribed ANODYNE NECKLACE, at that time deemed a sort of CHARM against the disorders incident to the children; and near the fire, a tobacco-pipe and paper of pills (115-116).

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 5: Broken China

Quennell

Mercury-treatment, or salivation, has been tried without success; the advertisements of an “Anodyne Necklace” lies discarded on the naked boards, beside a heap of coals, a shovel, a chafing-dish and a broken plate (99).

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 5: Broken China

Lichtenberg

The explosion has overturned the little table and with it a spoon, a plate, an ink-bottle and pen, and a bulletin. The spoon has come off quite well, it lies on its hollow side and touches the clean floor as little as possible, thus differing from bread and butter, which always falls on the buttered side. But the plate!

Broken, broken is the lovely jar, there lie the fragments! (Gessner, Idylls)

This is a sad thing for a whole plate, but not quite so serious for a damaged one. From the visible fragments, at least, it would not be possible to piece together a plate capable of containing anything which the neighbouring paper poster could not hold equally well. The ink-bottle breaks and the earth receives in a wholesale way the black gall with which it was filled, and which as an ingredient of prescriptions and love-letters may perhaps have led many a poor devil to that very consummation. It has finished its service. The collar round the neck of the pen, which has saved it from ruin, protects it at least from further destruction, and even if it were trodden upon in the turmoil, which however will not amount to much in this comer, there is still another department where it could find employment. Isn't it a splendid thing to have apart from one's writing end also a wiping end? If as a writer you are no longer able to give instruction, stilum vertas! and you can still sweep. A moral which every budding author who has invested his spiritual and physical fortune in disastrous South Sea shares of wealth and immortality through writing should let his dry pen teach him every morning, before he dips it into the ink bottle to preach with it his revelations to the world. The poster advertises a practical scheme concerning a new method for curing all kinds of diseases by neckbands or necklaces. We can see an illustration there of the necklace in question. At the top is the word 'Anodyne' written from right to left, and below from left to right the word 'Necklaces', which even in the original is difficult to read. The lines are meant to curve rather in the form of a neckband, for they really make a circumscription, a sort of band around the neckband, and perform here in reality for the project the service which the project itself merely promises to the patient. Thus 'Anodyne Necklaces', necklaces which are to take away pain A circle of words, half Greek and thus half mystical, drawn round an entirely mystical amulet, could not fail of its purpose with a certain class of person. It is really incredible, the success that device has achieved—I mean the outer band around the inner one. For whether the inner one had benefited the patient himself has not, as far as we know, become public knowledge, if we except the wall mentioned below. However, that poster does not lie here simply as a satire upon the innumerable advertisements for medicines which in London are daily thrust unstamped into people's hands, and even into their pockets, by some kind of postman; its meaning lies much deeper. This is one proof out of many which we shall come across that Hogarth in his works, just as Nature in hers, knew how to achieve, often with one and the same touch, more than one end, and knew also how to spread warmth where one might have thought he only wanted to shine. For these anodyne necklaces were originally intended by their inventor only for the use of children suffering from the so-called English disease (the Rickets), about which the unfounded prejudice prevailed in England and in many parts of Germany that it is usually the fruit of tainted love. This, therefore, refers to the poor little bastard who near the fireplace there half kneels and half sits beside the chair of his dying mother, and who, untouched by that dying and by the learned bellowing of the disputing gentlemen, and by the screaming intervention of the woman who presides over all this, quite peacefully roasts over the fire his pain- alleviating chop. Considering that he may be suffering from rickets, he could from his size be about six years old; deducting these six years from the mother's twenty-three, brings her age when she was infected to seventeen. This is what Hogarth tells us by means of a slip of paper which lies there between the fragments of a twice-broken plate and some pieces of furniture of rather equivocal form. If the stout gentleman on the up- right chair there were to have been the inventor of these pain-alleviating necklaces, as he could well have been, the satire would acquire more branches still. For, as we remarked above, our learned doctor himself died through an anodyne necklace, the rope (laqueus anodymus), which the law prescribed for him, and which in London works wonders (57-59).

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 5: Harlot

View this detail in copper here.

Moll, used by clergy and her lovers, is here an instrument of the medical profession. This plate elucidates the doctors’ mistreatment of a patient for their own fame and fortune. Here, the dying Moll Hackabout is attended by two physicians. She is wrapped in sweating blankets, yet another ineffective syphilis cure.

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 5: Harlot

Uglow

Amid this turbulence and noise, the crashing and shouting, the hissing water and raging fire Moll’s life is seeping from her. She has no strength, no bite. She has been suffering the cure of ‘salivation’, wrapped in blankets to make her sweat the disease away, dosed with mercury that makes her gums swell and her teeth fall out--they lie to one side on a crumpled paper marked ‘Dr Rock’. She looks like a huge silent insect in a chrysalis, a shapeless bundle supported by her horrified old maid in a grim burlesque of the death of the Virgin (208).

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 5: Harlot

Paulson, Hogarth's Graphic Works

While the doctors are quarreling over the merits of their respective cures, Moll Hackabout is expiring, wrapped up in “sweating” blankets. The teeth on Dr. Rock’s paper are Moll’s, loosened by the use of mercury (the “salivation” for syphilis. Her old portmanteau us here, with “MH” on its top, a grim parallel to the “MH” smoked on the ceiling; it now contains her mask, her witch’s hat, and other masquerade attire (from Pls. 2 and 3) (148).

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 5: Harlot

Lichtenberg

she dies, and from the terrible consequences of pandemonial love. We should be grossly mistaking the intention of our great artist if we were to mince words here, provided we need use words at all. For it is hardly necessary. Everything speaks for itself. From the pale cheek and stiffened lips death has effaced the smallest trace of wanton charm, which art had erstwhile added from without or within. Closed for ever is the mouth from which, but a few months ago, flatteries or mild imprecations used to fly with double-tongued volubility at the passer-by, according to whether he fought weakly or strongly against its wiles; for ever extinguished is the eye that shot its glances around full of affected fire, less for the purpose of seeing than of being seen—and now it sees no longer, nor is seen. At this complete evaporation of all her cheap glitter in the sight of Death, she comes before him in the simple garment of her first naturally-good disposition, and implores his pity. She did not find it. Yet we would not wish to deny her ours—Quiescat! (52.)

The girl has fallen a victim to them [the quacks], and how else could such a duel have ended? She fought against death and had none for Second but her own natural constitution, good in itself but often injured, weary, and neglected at every opportunity. And yet, perhaps, being a young woman of 23, she might still have beaten her adversary. But He who knew this well had chosen for himself a pair of Seconds, each of whom could have taken up the fight alone against a dozen lives. That is why it went veni, vidi, vici, and suddenly there she lay. That this is the true explanation of the matter is all too evident. For if the toad and the salamander who are quarrelling here had not been Death's malicious Seconds, but had taken the side of Nature, they would even now be striving to resuscitate the girl, whereas they are leaving that to—the last Trump, and merely quarrel about who is to have the honour of the deed. This mixture of mine in this glass, says the toad, was the true oil on the fire; and my fire, shrieks the salamander, had no need of your mixture. What a conflictus pronominum! (55).

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 5: Rock

View this detail in copper here.

Here, the dying Moll Hackabout is attended by two physicians. Although Peter Quennell identifies the corpulent one as Spot Ward (98), known for his wonder pill, most other commentators believe him to be Dr. Richard Rock, who also made a reputation for a cure-all known as the “famous, Anti-Venereal, Grand, Specifick Pill.” This identification is supported by a prescription signed by Rock, held in place by Moll’s teeth, compromised by her mercury cure. Rock is also pictured setting up shop in “Morning.” The other physician is consistently identified as Dr. Jean Misaubin, another pill doctor and the object of Fielding’s scalding wit. He dedicated The Mock Doctor to Misaubin and writes in Tom Jones that the doctor was so confident of his reputation that he used to say that the proper direction to him was “To Dr. Misaubin, in the World.” Hogarth also uses Misaubin as his quack doctor in Marriage à la Mode. Moll’s naiveté has also led her to invest in the anodyne necklace, the advertisement for which appears on the floor.

Ireland and Nichols comment that each of the physicians is accusing the other of poisoning Moll (115); however it does not appear that they are concerned with her at all. Neither doctor even looks at his patient, and their violent quarrel over the effectiveness of their respective cures, disrupts tables and chairs, continuing despite Moll's attendant who pleads with them to either cease their dispute and honor the solemnity of the occasion or attempts to attract their attention to the suffering patient. Their fine dress contrasts with Moll's attire—a sheet used for sweating cures—and with her impoverished surroundings which imply that much of Moll's money has been spent on her ineffective cures. Misaubin literally has his back to the patient, a pose that many of Moll's potential benefactors have adopted. Most notably, is a parson striking the same pose in the initial plate of the series, setting the tone of neglect that will follow Moll through her life. Her tragedy could have been prevented, or at least lessened, if the clergyman had been less concerned with his letter, likely soliciting a position from its addressee—the Bishop of London. He, like the doctors of Plate 5, is more occupied with his own advancement than with the obligations inherent in a life of service. Hogarth, then, indicts them all. An additional level of irony is that the one figure consistently devoted to Moll is her noseless, syphilitic servant who demonstrates more humanity than those dedicated to its improvement.

Commentators disagree about this identity of this doctor. Most believe him to be Richard Rock, who erects his sign in the “Morning” plate of the Four Times of the Day series. Others identify him as Dr. Ward.

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 5: Rock

Shesgreen

Two expensively dressed parasites (identified as Dr. Richard Rock and Dr. Jean Misaubin) quarrel violently over the efficacy of their cures as their patient-victim expired unattended in their view (22).

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 5: Rock

Uglow

In the middle of the scene two quacks argue violently, sending chair and table crashing to the ground, one being the fat Dr Rock, inventor of the 'famous, Anti-Venereal, Grand, Specifick Pill' and the other the thin Dr. Jean Misaubin, creator of a rival cure (207).

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 5: Rock

Paulson, Hogarth's Graphic Works

The two doctors in consultation were well-known for their quack cures for venereal disease. The fat one in the full-bottomed wig is identified by the added inscription on the paper holding the teeth ("Dr Rock") in state (3) as Dr. Richard Rock, “The famous Anti-Venereal, Grand, Specifick Pill,” advertised in the Craftsman (Feb. 24, 1732/3; see also Morning). Rock (1690-1777) was also described in similar terms by Goldsmith in The Citizen of the World (1762), Letter 68. The lean doctor is probably intended for Dr. Jean Misaubin (d. 1734), inventor of another famous pull for prophylaxis and venereal disease (Biog. Anecd., 1782, p.163; J. Ireland, I, 17n., 3,328; cf. the portrait-sketch by Watteau, etched by A. Pond in 1739 as Prenez des Pilules, BM Sat. 1987, and Hogarth’s Marriage à la Mode, Pl.3). Fielding satirized him about this time in The Mock Doctor, which opened June 23, 1732 (148).

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 5: Rock

Paulson, His Life, Art and Times

The two quarreling doctors in Plate 5 offer the basic choice of bottle or pill. Most are bottle cures—the “Anti-Syphilicon,” 6s a pot, and the “Diuretic Elixir” for “Gleets and Weaknesses,” 5s a bottle. Another was Dr. Rock’s “incomparable Electuary.” “the only VENEREAL ANTIDOTE,” 6s a pot, sold at the Hand and Face near Blackfriars Stairs; Hogarth inserts Rock’s name in his revised plate of 1743. As to pills, Misaubin’s famous brand (which however does not appear advertised in the papers until a later time) there were “the famous Montpelier little BOLUS . . . so immediate a Cure, That of those Numbers that daily take it, not one fails of having the Infection carried off by 1,2,3,or 4 of them, as the Distemper is more, or less upon the Person”; or “the long experienc’d Venereal little Chymical BOLUS”; or the “famous Italian Bolus.” Hogarth’s pill doctor, according to contemporary report, was a portrait of the French empiric, Dr. Misaubin, who also appeared frequently in the papers; typically in December 1730, Misaubin, “in St. Martin’s-Lane, gave a magnificent Entertainment to several Noblemen of Gentlemen, in which Company was Sir Robert Flagg, Bart. Of Sussex” (vol. 1 254).

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 5: Rock

Ireland

The two quacks, whose injudicious treatment has probably accelerated her death, are vociferously supporting the infallibility of their respective medicines, and each charging the other with having poisoned her (The meagre figure is a portrait of Dr. Misaubin, a foreigner, at that time in considerable practice) (115).

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 5: Rock

Quennell

Two doctors are arguing her case, one of whom was recognised by Hogarth’s contemporaries as Dr. John Misaubin, quack-specialist in venereal diseases and inventor and purveyor of a well-known prophylactic pill. Dr. Ward (Ward’s Pill is mentioned in Tom Jones, where it is described as “flying at once to the Part of the body on which you desire to operate.”), his companion, has also a specific ready; for this was a period when English medicine, despite the rapid advance of scientific knowledge, was still in a confused and daringly experimental stage, and almost every renowned physician had evolved and given his name to some mysterious private concoction—his powder, elixir or drop, reputed to relieve the symptoms of several different illnesses. So the pill-mongers have hot into a noisy dispute; and, while Misaubin bullies and scolds, his plump colleague appears to be waving him away with the gold-headed cane he is carrying as his wand of office. That cane was the doctor’s badge, its gold knob being raised to the lips and gravely gnawed or nuzzled at, as he bowed over the patient’s bed and prepared to announce his considered opinion. By no opinion or remedy can they hope to save Moll Hackabout (98-99).

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 5: Rock

Dobson

The wrangling practitioners in Plate V. are said to be Drs. Misaubin and Ward, two quacks of the day (35).

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 5: Rock

Lichtenberg