A Harlot's Progress: Plate 6

1732

11 13/16” X 14 13/16” (H X W)

View the full resolution plate here.

View the copper plate here.

In this last plate of A Harlot's Progress, Moll Hackabout's death is being "mourned" by an unusually distracted collection of attendants. While some figures are dressed in mourning, there seems no actual sadness for death. There is, however, a difference here between what SEEMS and what IS. Two women in the background appear to be crying, but their tears are more likely due to the alcohol they are consuming than to actual grief. Moll's son in the foreground appears pensive and concentrated, but he is actually busying himself with a toy. This dichotomy between appearance and reality harkens back to PLATE I. Here, a bawd welcomes the newly arrived Moll to London. Her touch, while seeming a gentle caress accesses the merchandise. Furthermore, in both plates, she is ignored by clergymen, who literally turn their backs on the situation. Our amorous man of the cloth here fondles his female companion while his drink spills into his lap in an ejaculatory fashion. While Paulson comments on the "father" figure (that is, the clergyman's) there is also notably the mother, here Mother Needham and her more active role in Moll's demise (Life vol. 1 253). The only dependable force in Moll's life, her sister of sorts, is the syphilitic servant who attends her and who is the only true mourner in this concluding plate. This is a dysfunctional family indeed.

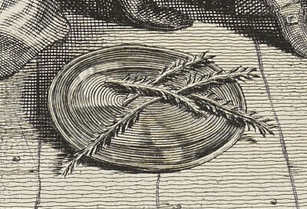

The clergyman's companion is another noteworthy figure. Her gaze, out of the plate and at the viewer recalls PLATE III where Moll gives us almost the same look. Commentators have typically seen PLATE III as the point where Moll's luck drastically reverses. Here, the nightwatch is breaking in to search for her watch-thief highwayman lover. Her room's decrepit condition is a distinct change from her more luxurious life as a kept woman. However, there are remnants of Moll's power, ones that show she still has considerable authority. First, she is literally ON TOP of her lover who is hiding under the bed (as betrayed by the cat). The hat and twigs indicate not only a potential preference for flagellation but hint at witchcraft, both of which demonstrate female power. Moll attracts the gaze of the viewer, as does the woman in this plate. So Moll's power does not die with her, and she and the foregrounded woman become sisters in subversion--her power over the clergyman is apparent. Another hint at this connection is the presence of the twigs (here seen in the lady's hand and on the plate). Although commentators have alternately called the twigs yew branches and rosemary, they are certainly reminders of branches in Moll's broom in PLATE III.

However, while these objects and this gaze demonstrate a type of female power, it is a temporary and transient one, one that does not originate with her, one she does not fully possess and one that does not help her to evade her fate. In this series, death has no real impact--nothing changes. There is no grand realization of the need to change London's corruption of innocent girls. There is no grieving for the loss of life. There is simply persistence, of all the elements from previous plate--thievery, vanity, lust, indulgence. The forces of corruption that contributed to her downfall are still intact, even in this funeral scene. Peter Quennell states, "If Hogarth had a message to impart, in A Harlot's Progress, at all events, it is not a message of a very lofty kind. That vice seldom pays is the only conclusion we draw. Unlike Defoe's more submissive heroines, Moll Hackabout does not round off a life of indulgence by paying lip-service to the beauties of virtue. So far as we can ascertain, she has never repented . . . Moll dies at the age of 23 and it is the wastefulness rather than the intrinsic wickedness that seems chiefly to have moved Hogarth" (102). But there seems to be no real disdain for her either. Hogarth's condemnation, then, is for the society that allows such things to happen--Moll is not an important figure. If this were the case, the series could have ended with her death in PLATE V, as Jenny Uglow reports that many viewers desired (208-209). Instead, here in the culminating plate, Moll is not visible. The coffin here is downplayed; Shesgreen even comments that it is being used as a bar (23).

The figure which catches out eye most immediately is that of Moll's legacy, staring at us from the plate. The central figure, Moll's son, further underscores the fact that Hogarth is not specifically blaming her. Uglow notes, "One sign of Hogarth's respect and compassion toward Moll in 'The Harlot's Progress' is that she kept her child alive, and even when she herself was dying in squalor, her boy was fed and stoutly clothed" (326). Unlike the Sqanderfield offspring from Marriage a la Mode, this young boy shows no sign of the syphilis which killed his mother and has almost certainly affected him. I see no real signs, then, in this series, and especially not in this plate, that Hogarth indicts her as complicit in her own ruin.

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 6

Shesgreen, Sean. Engravings by Hogarth. (1973)

Moll, dead at the age of twenty-three, is being waked. The plate on her coffin reads: "M. Hackabout Died Sepr 2d. 1731 Aged 23." Nobody mourns her passing as the mock vigil held for her. Leading lives that are without options, her sisters have little to learn from her death. Gathered around her coffin, they exhibit a variety of contrasting attitudes toward the occasion. Their spiritual leader, the clergyman (identified by Hogarth as "the famous Couple-Beggar in The Fleet"), who is supposed to give a religious tone to the event, has his hand up the skirt of the girl beside him. His venereal preoccupation causes him to spill. The fact of the girl who covers his exploring hand with a mourning hat is filled with a look of dreamy satisfaction.

Before the coffin Moll’s son, decked out grandly as the principal mourner, plays with his spinning top. At the right side of the scene an old woman, probably Moll’s bawd, howls in a fit of tears inspired as much by the brandy bottle at her side as by considerations of financial loss. Behind the bawd, an undertaker oversolicitiously assists a girl with her glove she postures as if in grief as she steals his handkerchief. At the mirror a girl adjusts her headgear vainly, oblivious to the prominent disease spot on her forehead. A weeping figure shows a disordered finger to a companion who seems more curious than sympathetic.

Only one person lifts back the coffin lid (which is being used as a bar) to look in detached curiosity, rather than in grief or reflection, upon Moll’s corpse. In the background two older women huddle together demonstratively and drink. The only person with a sense of decorum is Moll’s maid, who glares angrily at the conduct of the parson and his mate. Above the scene stands a plaque showing three faucets with spigots in them, the ironic coat of arms of the company (23).

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 6

Paulson, Ronald. Hogarth’s Graphic Works. (1965)

On the coffin-plate is inscribed "M. Hakabout Died Sepr 2 1731 Aged 23", and a mocking set of armorial bearings for the deceased hang on the back wall (needless to say, such did not accompany the funerals of whores): "Azure, parti per chevron, sable, three fossets, in which three spiggots are inserted, all proper." Sprigs of yew appear on the coffin lid and on the plate at the parson’s feet, and the lady beside the parson holds a sprig of rosemary for remembrance. Both yew and rosemary were employed at funerals because they were thought to prevent infection. The chief mourner is the little boy, the Harlot’s son, with his large black felt hat edged in broad lace. The ribbons on his and the parson’s hats are weepers. The boy is unconcernedly winding up a peg-top (or "castle-top," as some of the versified descriptions of the print call it). Only the noseless servant woman shows any sincere sorrow, and she casually uses the coffin lid as a table to set her glass on. The girl looking into the coffin is doubtless regarding Moll as a momento mori. The woman behind her is weeping because of her finger, which appears to be diseased in some way. The parson is using his hat to conceal what his right hand is up to, but in his concentration he spills his Nantz (brandy). The undertaker, or mercer, who handles the funeral, is making advances to a prostitute by the window.

In the copy published by Bowles the parson is labeled "A" and is explained as "The famous Couple-Beggar in The Fleet, a wretch who there screens himself from the justice due to his villainies, and daily repeats them"—i.e. he celebrates clandestine or irregular marriages. He has also been identified as "Orator" Henley, but so has ever disreputable person in Hogarth’s oeuvre (and this parson resembles Henley much less than the parson in Midnight Modern Conversation, Plate 134). The woman with whom he dallies has been tenuously connected with Elizabeth Adams, who was hanged in January 1737/38. Some of the other characters have been identified, but with no certainty and to little purpose. The woman at the far right, according to Breval, was "Mother Bentley, a noted Bawd"; and since we know that the noseless woman is the servant of earlier plates, the woman at the right must be Moll’s bawd. This explains her passionate lamentation.

Charles Mitchell detects a resemblance between Hogarth’s composition and a print from an ars moriendi blockbook (148-149).

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 6

Paulson, Ronald. Popular and Polite Art in the Age of Hogarth. (1979)

Hackabout appears in the compositions of Mary the Mother in the Visitation, the Annunciation, and the Death of the Virgin—and her funeral is a parody of the Last Supper. Are these merely inverted parodies, like Milton’s Satan, Sin, and Death of the Holy Trinity or Pope’s Dullness holding Cibber’s head in her lap of pietà? Are they projections of the Harlot’s imagination in which a Mary Magdalen thinks of herself as the other Mary (as Hubridas’s Quixotic imagination is represented by Hogarth in graphic terms as baroque processionals and battle scenes or as Mr. Peachum in the Beggar’s Opera paintings assumes the pose of Christ in a noli me tangere)? Or are they in some deeply popular sense a naturalization and reduction of sacred materials to a joke –the refusal to see paradox? (19-20)

But as a more purely visual pun, the sign (the bell from plate 1) anticipates the obscene coat of arms of the Harlot that hangs among her funeral decorations in the final plate: "azure, parti per shevron, sable, three fossets, in which three spiggots are inserted, all proper." The image of faucet and spiggot or bell and clapper is carried further in the "frail china jars" that are the broken teacups of plate 2. Out of the signboard principle of punning visual equivalent Hogarth projects a powerful, yet almost subliminal, image wihc dominates (in, of course, a peripheral way) A Harlot’s Progress. It is, at the same time, a literary emblem, carrying memories of cracked crystal, the china scene in The Country Wife, Priest Crowne’s lines "Women like Cheney shou’d be kept with care,/ One flaw debases her to common ware." and Belinda’s honor as a "frail China jar" . . . the Harlot’s escutcheon indicate[s], is, first, the whore’s need for respectability and, second, the close relationship between popular signs and the heraldic arms of the nobility. They share the origin of their graphic forms in profession and name, in fact and in identity, but turned into the accidental resemblance of a pun.. . . .Indeed, the escutcheon and the shop sign are merely two forms, one high and the other low, of a single attempt at self-identification, which can be traced back to examples in ancient Rome (34-35).

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 6

Uglow, Jenny. Hogarth: A Life and a World. (1997)

Some commentators felt that the series should end here [Plate 5], with Moll’s death, the wages of her sin. But Hogarth’s bitter comedy insists that life goes on, Like a satirical afterpiece following a tragedy, his last print shows the mourners before Moll’s funeral. Scene by scene, from the open air of the coachyard Hogarth tracked his heroine’s increasing confinement down to her last tight space, her coffin. One young woman looks at her face, hidden from us. Around this gesture of pity and, perhaps identification, women stand in extravagant stage poses of grief. Hogarth marks the pompous rites of death favoured by this age, and by baroque art, by showing the indifferent callousness of life. The erotic play continues to the end, and viewers (or voyeurs) might laugh more than weep. The clergyman, spilling his brandy, has his hand up the skirt of a demure-looking woman who coyly hides his gropings with her hat. The smooching undertaker helps a whore with her funeral gloves, while she steals his handkerchief. The little boy, in full adult gear, with lace around his black felt hat, examines his spinning-top oblivious to the fuss, a study in absorbed concentration from his open mouth to his feet, dangling down in their buckled shoes. On the far wall hangs the mother’s old country hat, next to a satirical-obscene coat of arms made up of three faucets, plugged with spigots. On the floor in front of them al lies a dish with sprigs of rosemary—for remembrance (208-209).

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 6

Dobson, Austin. William Hogarth. (1907)

. . . the clergymman (!) of Plate VI is identified with a certain disreputable Fleet chaplain, and the shrieking beldam with a procuress named Bentley (35).

By some of the commentators this final plate (The Funeral) has been regarded, not only as involving a certain neglect of probability, but even as being in itself an anachronism and a superfluity. This was the opinion of Hogarth’s own instructed interpreter, Rouquet. To him the tragedy finishes naturally with the fifth picture; the sixth is simply the farce, or after-piece—"une farce dont la defunte est plus tôt l’occasion que le suject." Dr. Trusler follows Roquet so closely as almost to quote his words. The plate he says, is "the farce, of which, death is, oftener, the occasion than the subject." That (as both imply) Hogarth—like Goldsmith later—intended to satirise the senseless funeral ceremonial of the day, and that in doing so upon the present occasion he has somewhat strained consistency, is true. But it is also true that he was wiser than his critics, and that all this was merely subsidiary to a deeper and sterner lesson, more intimately connected with the subject. What other epilogue, indeed, could there be to such a life! Conventionalism, no doubt, would have stepped in with its ready tear and faded "Resquiscat." But Hogarth scorned Conventionalism, and copied human nature, hard-hearted, frivolous, unrepentant, incorrigible. In his experience, harlots were harlots to the end of the chapter—and after. There were no magdalens among them. Their mourning was a mockery; their priest a profligate. He will not even have the poor child impressed;--how should he be with such a mother? No, let him wind up his "castle-top" in the foreground—"the only thing in that assembly (as Lamb says) that is not a hypocrite." This painter painted life as he saw it; he cared to do no more (35-36).

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 6

Quennell, Peter. Hogarth’s Progress. (1955)

Finally, we arrive at the funeral party—a ceremony of leave-taking attended by professional friends, at which gin and tears are confusedly mingled. Only the bunter had seen Moll die; now only the bunter, who clutches a glass and flagon, displays the fixity of real grief. Sighing, sipping or improving the occasion with some pious sentiment, the ladies of Drury Lane, in their gloves and mourning-hoods, are assembled as members of the chorus to descent upon the harlot’s end. Some are lacrymose; some are confidential; some quickly pass thanks to the influence of Hollands, from solemn valediction to surreptitious byplay. Near the sprigs of rosemary arranged on a platter, the chief mourner sits swaddled in his weeds and, being a philosophic and much-experienced child, devotes his attention to his brand-new spinning top. Hogarth’s sympathy with the characters of children clearly extended to an appreciation of their intermittent callousness; or, rather, he would seem to have understood what narrow and arbitrary limits confine their powers of suffering. But at least the child’s indifference is a form of innocence and just above him, as he sits by the coffin, Hogarth has placed two of the oddest and most subtly ill-favored of all his adult personages. The clergyman, who will conduct the funeral,, so the portrait of a "Fleet Chaplain," a shady cleric established in the purlieus the gaol, who earned his keep by the celebration of clandestine or irregular weddings, A soft, slippery, sheep-faced man, whose dull prominent eyes, which goggle straight ahead, are beginning to brim over with a vague concupiscence, he spills his flask of gin into his lap, while his fingers make tentative explorations among his neighbour’s petticoats. She does not repulse, but pretends to ignore his sally, attempting, however, to conceal it behind the wide brim of his mourning-hat. This decorous and resourceful female was accepted as a likeness of Elizabeth Adams, a demi-mondaine destined to be convicted of theft and hung in 1737. The dwarfish mænad at the left of the stage recalled a bawd named Mother Bentley (99-100).

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 6

Paulson, Ronald. Hogarth: His Life, Art and Times. (1971)

The final painting was presumably finished Thursday, 2 September, 1731, the date on Moll Hackabout’s coffin; at any rate, Hogarth seems to have intended this date to signify the completion to the series, as an allusion to a private memorial. Perhaps he was amused by the anniversary of the Great Fire of London on that day (noted in the newspapers of the third) (vol. 1 255).

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 6

Ireland, Priest and Priest Nichols. Hogarth’s Works. (1883)

The adventures of the heroine are now concluded. She is no longer an actor in her own tragedy; and there are those who have considered this print as a farce at the end of it: but surely such was not the author’s intention.

The ingenious writer of Tristram Shandy begins the life of his hero before he is born; the picturesque biographer of Mary Hackabout has found an opportunity to convey admonition, and enforce his moral, after her death. A wish usually prevails, even among those who are most humbled by their own indiscretion, that some respect should be paid to their remains; that their eyes should be closed by the tender hand of a surviving friend, and the tear of sympathy and regret shed upon the sod which covers their grave; that those who loved them living should attend their last sad obsequies, and a sacred character read over them the awful service which our religion ordains with the solemnity it demands. The memory of this votary of prostitution meets with no such marks of social attention or pious respect. The preparations for her funeral are as licentious as the progress of her life, and the contagion of her example seems to reach all who surround her coffin. One of them is engaged in the double trade of seduction and thievery; a second is contemplating her own face in a mirror. The female who is gazing at the corpse displays some marks of concern, and feels a momentary compunction at viewing the melancholy scene before her: but if any other part of the company are in a degree affected, it is mere maudlin sorrow, kept up by glasses of strong liquor. The depraved priest does not seem likely to feel for the dead that hope expressed in our liturgy. The appearance and employment of almost every one present at this mockery of woe, is such as must raise disgust in the breast of any female who has the least tincture of delicacy, and excite a wish that such an exhibition may not be displayed at her own funeral.

In this plate there are some local customs which mark the manners of the times when it was engraved, but are now generally disused, except in some of the provinces very distant from the capital sprigs of rosemary were then given to each of the mourners: to appear at a funeral without one, was as great an indecorum as to be without a white handkerchief. This custom might probably originate at a time when the plague depopulated the metropolis, and rosemary was deeded and antidote against contagion. It must be acknowledged that there are also in this print some things which, though they gave the artist an opportunity of displaying his humour, are violations of propriety and custom: such is her child, but a few removes from infancy, being habited as chief mourner to attend his parent to the grave; rings presented and an escutcheon hung up at the funeral of a needy prostitute. the whole may be intended as a burlesque upon ostentatious and expensive funerals, which were then more customary than they are now. Mr. Pope has well ridiculed the same folly: "When Hopkins dies, a thousand lights attend/ The wretch who, living, saved a candle’s end."

The figures have much characteristic discrimination: the woman looking into the coffin ahs more beauty than we generally see in the works of this artist. The undertaker’s gloating stare, his companion’s leer, the internal satisfaction of the parson and his next neighbour, are contrasted by the Irish howl of the woman at the opposite side, and evince Mr. Hogarth’s thorough knowledge of the operation of the passions upon the features. The composition forms a good shape, has a proper depth, and the light is well managed (117-120).

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 6

Lichtenberg, G. Ch. Lichtenberg’s Commentaries on Hogarth’s Engravings. (1784-1796). Translated from the German by Innes and Gustav Herdan (1966)

She was thus carried off before she had time to become pious. She was fortunate in that, for there are instances of pious dames of her cloth having been hanged. Oh! how much could we not say here—if we were allowed to say it! But we fear the prayers of the pious, respect the coffin-lid, and—are silent.

If we survey that fathering only cursorily or from a little distance, we are almost ready to believe we have seen something like that before somewhere in the world, and expect to fin something sad but still genteel. A coffin over which they are murmuring a tender "Sleep well!": a lot of crepe; a figure like a parson and another like a sexton; a funeral escutcheon on the wall; a child in deep mourning; rosemary, tears, and white handkerchiefs; they are waiting for the hearse. Who in all the world would suspect anything reprehensible here? But just bring your eye a little nearer so that the parts become individually distinct, and you will find that you have never seem anything like that before anywhere. Everything changes and even partly vanishes. There is crepe without mourning and howling without tears; not a trance of a parson nor of his sexton the arms are a lampoon and the very coffin a counter—from brandy. It is abominable! Now guess what is going on here? This the reader will now partly hear and partly guess quite easily.

The room into which we are looking here is either a room on the ground floor of the house wherein our heroine died, or it belongs to the man who, against a certain gee, takes complete charge of the corpse. This is the man here with the sexton face. The female part of the company consists entirely of sisters, prioresses and abbesses of the Order of strict observance to which the deceased belonged, undeniably one of the most numerous in the world. The Sisterhood of Drury Lane is said to comprise more nuns than London has hackney-coaches, whose number is estimated at a thousand; and though strict vigils and the martyr’s death kill quite a few of them ever year, and transportations to Jackson’s Bay have made considerable in-roads, there is not the slightest noticeable diminution. They are waiting here for the removal of the coffin, which does not seem to happen quite on time. It is usually so with departures, except perhaps the departure from life, where everything happens much to soon: with the removal to the churchyard, on the other hand, the procedure is often as unpunctual as if one were hale hand hearty. However, they know what to do here; they amuse themselves as best they can.

In that gathering there are thirteen living people, one dead and then a sort of intermediate one, a picture in the mirror, thus fifteen altogether. Of these, three are standing by themselves, the other twelve are arranged in pairs. Two pairs of living ladies together with those separate subjects make seven; a living lady, paired with a dead one, makes nine; two highly alive Chapeaux with two ladies of the same quality, makes thirteen; and finally a lady with her reflection in the mirror—in the same capacity as the lady herself—gives fifteen. We shall have something to say about each, even if only a word. We begin with the left wing.

What strikes the eye immediately here is the big gun which has been posted at the flank. If compared but perfunctorily with the figure sitting beside it, it could easily be taken for a tear-bottle, but for this the shape has obviously far too much of the mortar and howitzer. It is really a drinking gun, a six-pounder at least, loaded with Nants (French liqueur). Very peaceful and merely serving the function of bonfire and fireworks for the column. The counterpart, a small mortar, is to be found near the right wing upon the coffin-lid, and for the same purpose. This fire from the wings, as we shall see, has an uncommon effect upon the centre. The moment has been excellently chosen by the artist. It is, in effect, the moment when age exalted by Nants approaches the feelings of youth, and when the gathering resembles the beautiful picture of the snake which with tail in mouth coils itself into a circle, to which everything perfect in the world must eventually more or less conform. It will stay like that-provided the hearse is not too long in coming and the coffin does not lose through the delay the respect due to it. But let us now examine a little closer how things stand.

The artillery is well served. The small mortar is taken charge of by the snub-nose whom we already know, and the howitzer by the fire-toad who in the corner there wrings both her fore legs and stretches out a hind leg. If someone does not know what tragicus boatus is, he should look if he dares at that face. It does not bear illumination, and is in need of none; we only beg our readers to note that what shines so charmingly in the lovely mouth of that female gunner are not teeth (for of these she has only a few), but the most indispensable part of her swallowing-cursing-and-praying apparatus--her own unsmoked tongue. She seems as if born for her department, and the howitzer form of her waist cannot be mistaken, at least it would hardly be possible in a human being for the ends A and B to be nearer one another than here; a deft surgeon could attend to both with one hand. Moreover, it almost goes without saying that she only sits like that so long as she is not drinking or pouring out. Might it be the woman who was kneeling in front of the coffer in the last Plate? The faces, to be sure, are not quite alike, but Laocoon also looked quite different on the day before his misfortune from how he has looked these last few thousand years. And the figure? Well on such a day one puts on all the clothes one has.

Next to this Patagonia face, which is one of the unattached, we see the first of the couples, of European-London culture. Mr Undertaker, who is helping one of the nuns to don her mourning-glove, makes use of that favourable opportunity to submit to her a little request of easily understandable tenor, and he does so with such good manners and with so much modest fervour that it cannot possibly remain without response. In fact, there is already something like the reflex of a gracious permission in the very eye of the supplicant, although the sign by which it was granted is not disclosed. But his assistance in putting on the glove was probably given in the form of a question, and thereby gave opportunity for a reply which, however, had to remain invisible. The contrast in these two faces is capital: the undertaker has no other design but what eye and mouth betray, he is utterly concentrated and as one-sided as possible-for the moment, at least; the girl's eye on the other hand speaks of all-sidedness and design. However dim it may seem, it certainly is not only the Spiritus rector of this assembly which is dimming it; there is play-acting here which would betray itself by the obvious traces of a triumphant smile at the blindness of the poor trapped devil to anybody who does not happen to be that poor devil himself. Drury Laneites do not forget themselves. With them every movement, no matter how small, is meant not only for the hearts which they openly attack, but, at least secretly, for their handkerchiefs as well. No sooner does the harpy learn with the surface of her right arm that the heart is full, than she already begins stealing with her left. This is the so-called small souvenir from Mr Undertaker; the big one will follow suit.

Immediately after that first mixed couple come the four unmixed ones, one after the other, if we go from the left wing towards the right; the first of them represents an inspection. Both members are, as we see, of slightly more than middle age. In both can be observed a praiseworthy and most reasonable economy of bosom, with which the young, thoughtless vermin here are not yet willing to conform. One of them seems already of an age when spectacles can be mislaid. As we see, they are needed here. The second, a lean sufferer, has something between the fingers which seems to cause her pain and which is being examined by the first with surgical, serious, and really expert touch and subtlety. What could that be? Or is it perhaps nothing at all, and only signifies something? To be frank, we almost suspect here (Greek may do it) deep esoteric wantonness under a completely esoteric mask, about which, of course, one is free to say what one likes. Oh! how agreeable it is for a commentator if he can slink away from a difficult passage to which he has merely opened the door for the reader, without saying anything more than a few conjuring words in Greek. The sufferer has warts on her fingers and, as is well known, the dead know better how to remove warts than the living. The lady without spectacles seems to think only of ways and means of bringing a wart between the fingers in contact with the corpse. The problem is not easy. If the nose will not do it, nothing else will. This makes the poor creature cry. But only think what a rogue our artist is, even in his disguises. He conceals a wanton thought and the concealment itself is again an act of wantonness, deep too but more comprehensible than the first, though quite unconnected with it. I have heard of a type of politics, deep and unfathomable, being disguised as another, also deep but fathomable, and unconnected with the first (newspaper politics), but I never heard of this sort of satire. The wart-remover, who is in charge of the operation here, has two of them herself, but on her brows like horns sprouting. Having brought the interpretation as far as this, the moral becomes easier and easier, which is evidently that of the beam and the mote and the brother's eye.

Behind that pair stands the third; a pious sister in conversation with another, who shall have no name, in the mirror. Undoubtedly the happiest couple of them all. In every combination by pairing in this world, a certain compensation of defects and accomplishments in the subjects is necessary if the common happiness is to be lasting. What you lack, I have, and what I lack, you have, is the firmest foundation. But in the combination of which we are speaking here, that is quite unnecessary, and for complete satisfaction it is quite sufficient if only one of the members either has every possible accomplishment or, what amounts to the same thing, believes she has them. Thus in our case the girl who presents her back to us is young, and beautiful, or at least she thinks so herself; now if this is granted she need not care a jot about the characteristics of the other, and yet only see with what loving admiration they gaze at each other; like two angels who pass and do not know one another. Each sees in the other a higher creature, each admires and is admired, each bends the knee and the scene ends in mutual adoration.

We shall postpone for a little while our contemplation of the fourth couple, that is the union of the living and the dead women, because Hogarth has used them, and rightly, it seems to us, as the coping stone of the Ark; we shall turn now to the right wing, and thence proceed towards the zenith, as we did before with the left.

Of the pair who fill the right wing, we have a good deal to say, and even more to be silent about. Hogarth's honour demands the one of us, and the respect which we owe to our public the other. Yet the scene must and shall be understood, although we may have to take the liberty of not always writing expressly 'devil', but instead something like Mr Satan, or a mere d….

This time, he as well as she are admittedly portraits. The girl was a notorious creature called Mary Adams who after innumerable acts of debauchery, committed while she was a young girl, was ultimately despatched in her thirtieth year, not to the New, but because of very aggravating circumstances, to the Other World, for theft. She was hanged on September 50, 1757. Portraits have been made of her, and the present one is thought to have been modelled on one of them. Now since these Plates had already appeared in 1754, and thus three years before her death, we can infer from it, at least, that she owed her notoriety not to her last crime alone, or to the way in which she died. This might easily have been due to her personal charm, which the face does not lack even here, where English complexion and English teeth do not come into play, and where all the life which a beautiful face should express to the world seems bent in upon itself. The man beside her is not a clergyman. We beg our readers most earnestly not to entertain such a thought; anything like that would necessarily be prejudicial to the artist, and thereby the whole impression which this piece should make would be lost. There is merely a clergyman's frock. The thing inside it here is one of the few eminent scoundrels to whom Hogarth has justly accorded an infamous immortality; a Charters in his way. Would not the artist have done better, someone might ask, had he spared the cloth here as well? We regard that remark as very well founded; indeed, we are even convinced that it would have been better. But since that is how matters stand, we must hear the artist's defence as well. We undertake it with genuine pleasure and in the sure hope that he will be acquitted.

In his works Hogarth has made attacks on three occasions upon people in parsons' clothes, that is true; but that he ever attacked the profession of clergyman as such, we cannot recall. Out of these three, two are portraits of well-known people, about whose despicable character the voice of the public had already decided long before Hogarth voiced his opinion. He has thus done nothing but what every honest man had done before him, except that he drew and painted where others spoke or wrote. Whether the picture of the third is also a portrait, we cannot say with certainty, but it would still show no disparagement of an honourable calling if it were not. The fellow is only a bit of a gourmand, and on an occasion which regularly occurs but every seventh year. Apart from this he does not hide his doings in a corner, but makes his feast, so to speak, right in the lap of his constituency, before the eyes of his flock, who feast together with him, and it does not cost his family a penny. Such conduct can hardly be called reprehensible. But here, here the situation defies description. Hogarth certainly felt this very keenly. He therefore did something which he had never done in any of his works, so far as we know; something which is hardly compatible with his manner of satire (though in order to exonerate oneself completely, even such extraordinary methods may be necessary). On the 1,200 copies for subscribers, he marked that vile creature with a capital 'A' which referred to a footnote under the Plate where it is clearly stated who he was, and where and how he managed to escape the law. Now just imagine what a lawless creature that abomination must have been, when an honest, well-known and well-esteemed man like Hogarth does not scruple to draw him thus for all the world to see, and, in addition, virtually invokes justice against him. In this way, or so it seems to us, he has not only proved that he did not intend to attack the clergy's estate, but on the contrary, he has shown how much he had its honour at heart. When hunting out subjects for satire, an occupation which he tirelessly pursued, many an object that knew how to evade the activity of the police and the law fell into his snare, and he acted rightly in delivering them up to the authorities, or, if the authorities let them escape again through carelessness, in giving them at the next opportunity the coup de grâce himself.

This scoundrel, evidently the Spadille among the trumps in hearts, as the other black ace, the Undertaker, is the Basta, was so well known under the name Couple-Beggar (because he copulated for a few pence) that Hogarth's interpreters have forgotten his proper name, a feature which in itself speaks for his great eminence in the profession. We have been assured that, apart from that other occupation, he united himself regulariter a couple of times a week-with the gutter. Not only symbolically, as the Doge of Venice marries the Adriatic. Instead of throwing a trifle into it, he threw in everything which he still had left in the evening--himself. A Divine he has never been called, he was merely an adept at holding Divine Services, and even there he Just babbled through the Marriage and Funeral service-for a few pence. His spiritual hand, as it was called, never fished for more, but fished all the more often-while his worldly hand demanded stole-fees wherever they could be found, in pockets with and without bottom ad infinitum. This is well known. Whether Hogarth tried to hint at something of this sort here cannot well be decided. In his so-called spiritual hand, the left one, he holds the funeral brandy very badly and stains his handkerchief with it. Where the worldly one is, nobody, so far as we know, has yet been able to decide. People have looked for it under Couple-Beggar's hat, which the Manille is holding very carefully in front of it, but it has not been found there either. We therefore willingly abandon this locum difficillimum and pass over with genuine pleasure, in the way of commentators, to an easier one--to Snub- nose. She stands at the foot of her friend's coffin with a mortar in her hand, like a female sutler before the inn counter. I call that feeling! And yet, to the honour of human nature, there is in her wild look a kind of unmistakable disapproval at the behaviour of the neighbouring couple. It absorbs, as one can see, her whole attention, and although her mouth speaks of much latitude in such matters, yet her eye seems to find place and time and hour somewhat unbecoming. It is a fine touch of Hogarth's to put even into that unfeeling tiger-face an expression of disapproval at such bestiality, and thus to make even the stones cry out about it. In passing we would beg our readers to recall for themselves what that creature has done and suffered so far, and what sort of a life that is, and yet even as we read this, it is still lived by countless women! But we do not wish to prejudice the views to which this might give occasion about the inheritors of the Kingdom of Heaven and their spiritual guides!

Right in the background near the door we see the fifth couple. If anyone does not know yet what it is to be befuddled, he ought to look at this. We should almost like to melt with them when we observe how these two hearts, which probably are not yet entirely depraved, fuse into one. What bliss! They have the sensation of floating towards a Heaven of love and friendship, and do not realize that the house of cards erected by the liquor will, in the ensuing quarter of an hour, collapse beneath them and will send them with acceleration into the depths where police, pillory, quack doctor and the hemp beating association are ever ready to receive them.

One of the members of the sixth and last couple, the living one engaged in contemplation of the dead, Hogarth has not put for nothing into the centre of the picture. He wants us to take special note of her. Just as she is at the apex of the semi-circle formed by the assembly, where the two wings converge, so also converge in her role the moral lines which the artist here wishes to draw. That is why the girl is also one of Hogarth's beauties. This is a point to remember, for it might pass unnoticed. Moreover, the girl is not altogether bad. Youth and freshness are there at least, and to these qualities is addressed the moral which can best be expressed by the words from the coffin:

What thou art and how thou art, I was too but a short while ago. Abandon the path thou art treading; if not, think of this: what I am now, thou too shalt be, and in a short while.

Whether the little goose has heeded these words, cannot be ascertained from her face; but that, if she has heard them, she will have forgotten them even before the hearse arrives, this I think can be predicted with certainty.

Almost beneath the coffin, just as formerly beside the death-chair, sits again the little heir, occupied with a pain-alleviating instrument. There it was a chop which he turned on the spit; here he winds a top which he is going to spin in the chamber of mourning. It looks as if the anodyne had worked well on the little chap. However, it may also be that what one takes for the cause here is really the effect. The boy does not grieve, but not because he is roasting his meat and winding his top, but he roasts and winds because he does not grieve. Why should he fret? Just as he has no father, since nobody knew who he was, so he had no mother either, because in the society where he lived nobody had time to be one. Oh, the words father and mother mean very much more than we usually find in their dictionary definitions, and more than people think when they read them! Just as many a child whose true parents are far beyond the grave finds, thank God!, a new father or a mother, so, alas! there are fatherless and motherless orphans whose parents are thoroughly enjoying themselves day after day. Evidently the poor fellow has often been pushed from one corner into another; but since the decease there will be one pusher less. Even supposing that snub-nose will sometimes throw him into the corner now, there is still nobody near at hand to throw him back again. From the boy's puny legs we might almost conclude that the anodyne necklaces have not been of much use. That Hogarth has dressed the boy up as chief mourner is a mockery in more than one respect; children are never used in that role; it must always be a man of some presence who would not disgrace an afflicted heart. But the expression could also imply ''the chief among the mourners', and in this way the situation becomes almost ludicrous. For if the most deeply afflicted is winding his top shortly before the cortège leaves, we can easily surmise how deeply afflicted the others must be. The dish with rosemary as well as the little table with the gloves and the glove-stretcher for the too-narrow fingers are plain enough, but the position of the pair of gloves is perhaps not without intention. They seem to have moved apart as if shocked, and so as to clasp each other again, and to shame by their example at least ten pairs of hands of flesh and blood among the thirteen which are assembled here and are occupied in a somewhat worldly manner.

About the mourning escutcheon on the wall, although we shall describe it in accordance with our duty, we shall take good care not to give an opinion, either as regards the aspirations which are to be immortalized through it, or the demesnes which it is meant to indicate, since we value peace, together with an ounce of family pride, more than all the honour which we might perhaps win on this occasion with our heraldic penetration. The instrument which we see here in triplicate on the blue field is called in English 'spigot and fosset', better written faucet. It is a sort of bung for barrels. This consists, as we see, of two parts, of which the smaller, the spigot, is stuck into the larger, the faucet, just as the latter is itself stuck into the barrel. In drawing wine, only the smaller one is drawn out and, when the bottle is full, is pushed in again. It is the simplest cock in the world. Despite our promise, we should be glad of permission to add a little remark about that escutcheon because, as the reader will see immediately, our promise will not really be broken thereby. We only gave our word as regards the interpretation of pretended claims to relationships and demesnes, but by no means of the wanton misuse which our rogue of an artist could make of a matter quite innocent in itself. He has drawn the three cocks, probably with intention, in such a way that, seen from a distance, they could be taken for the three French lilies. Fine praise for the girl in her coffin to hang above it the French escutcheon! I believe the rogue would have liked to hang the three lilies themselves there had he not feared that one of the English Kings-at-Arms would rap his knuckles for it. Were Hogarth's English commentators apprehensive of some similar reward for their interpretations? Not one of them says a word about it.

In the window sticks a body of such equivocal substance and form that one is not quite sure whether it has been pushed in from the inside to close the gap, or from the outside, and in that case, whether it was not the object itself which made the hole it now fills. This latter type of interference with the glazier's trade is something to which the virtuous young hooligans of London are very prone, when they suspect so much vice in a room, and especially a funeral with the French escutcheon. One might even be grateful if they calculate the hurling of the missile in such a way that, as here, it cures at the same time the damage which it has caused.

Finally a remark about Roucquet's opinion of this Plate. He holds that Hogarth would have done better had he finished the story with the death scene, and he says of the present Plate, c'est une farce dont la defunte est pluto't l'occasion que la cause. We are accustomed to seeing Frenchmen often treat very serious matters as farces, and very trivial ones with gravity. This only means that with the French all things are possible. But Roucquet is really not entirely wrong. He has only missed the main viewpoint from which the picture must be apprehended, and has looked at it from another one, from which alas! it has also been conceived, and this in other words means so much as: Hogarth has really made a mistake. If Roucquet had hit immediately upon the first viewpoint, his whole criticism might not perhaps have materialized; Hogarth undeniably meant to say, as Gray in his superb Elegy has expressed it so beautifully, that even the most miserable and depraved, no matter how unsung they may die, find comfort in the respect of some they leave behind and long for it. It is not only insult after death (for who could remain insensitive to that?), but the mere thought of laughing heirs which embitters the last moments even of the most light-hearted. Do not the English regard it, for instance, as an aggravation of capital punishment if the additional sentence is pronounced that the body is afterwards to be taken to the dissecting room? And in other countries, is it not some mitigation if the headless body is to be buried not beneath the gallows, but in a corner of the churchyard? But what sort of funeral is it here? There are not many steps, to be sure, between this sort of honour after death and a burial beneath the gallows. This was undoubtedly Hogarth's idea, and the funeral scene fits very well into the whole, but how has he executed it? Certainly not particularly well. With such ceremonial; with a chief mourner who is only a child, and even the deceased's own child; with an escutcheon, an inscription on the coffin lid, and altogether with such pomp, no whore is buried in London, unless she were one of some social standing. Nichols says a cortège of that nature would not have been able to proceed, especially in those days, when the police were so very bad. Satire of course is there, but unity is missing, and looked at from that point of view, this sixth Plate does in a way acquire the appearance of a Comedy after the Tragedy (69-80).

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 6

Trusler, Rev. J. and E.F. Roberts. The Complete Works of William Hogarth. (1800)

In that garret abide Death and Silence. Its tenant is a rigid form—once so fair, so rosy, that men lusted after its beauty, and committed sacrilege upon the sanctuary which enshrined it.

Death and Silence! How passive they seem! yet how eloquent they are. What poetry they utter! What homilies they recite! "Vanities of vanities!" begins one: "Man that is born of a woman!" begins another. They mingle those dreadful litanies about sin, and death, and shine; but al this while Kate moves not. She is very still—still and cold as marble; she is very lovely now; and, oh! what a bring seraphic gleam is that playing upon her face, bringing back to her that old look of innocence, purity and childhood she once wore so becomingly.

The day is passing on, and the yellow light grows duller. The figure on the bed, which is something other than it was—something beyond the touch and taint of man, and therefore, partaking of the sublime--is still—the marble is not stiller. And the lights yet shift on.

Yes! Death hath been there, cleansing and purifying her poor despised remains—washing them in those water of Marah, which, however brackish, have still done something to the purifying of the soul, ere it fled starward. Death hath changed that corrupt, dishonored body into something so serene, so awful, and so beautiful that nay who had known the wearer in life, and held her in contempt or pity, as the case may be, would approach her now with a sense of something more terrible, more unreal, less earthly, pervading the quiet sleeper; and the most callous would have felt some unquiet creeping, and the haughtiest would have bowed the dead. Cold, shifting grey lights—now lapsing into twilight, now crepuscular, now dark, darker—the garret, with its one tenant, is now an awful sanctuary, which none dare approach.

It is night. The stars are out. There is moonshine too. Starshine and moonshine pour into the room by the narrow attic window. The serene silver light falls with a soft, pale radiance on the still face and the closed eyes. Is there not the old smile of childhood on the lips? and is she not as cold and beautiful as vestal chastity.

It is thy hour of triumph now, Kate. No petty rivalries, no mean jealousies can affect thee more, pore girl! Even thy sisterhood, that scorned or that cherished thee—for the unhappy creatures have their moments of fierce and hysteric tendernesses—they can sorrow for thee, pity thee they ought to envy thee now more than ever, for thou hast thine immortal jewels on; even they speak of the in whispers, and tremblings, and tears.

From the scores of surrounding streets—from the hundreds of alleys lying round and about—there comes a hoarse, deadened hum of human voices. Some are howling tipsy ballads far out below. Hoarse, brawling voices, as of men in altercation—shrill altos of venomous women quarrelling, with tigerish thirst to claw their opponents tooth and nail, rise upon the air. The costermonger lifts aloud his voice; the butcher cries. "buy! buy! buy!" the thousand-and-one street cries of the metropolis mingle together in one Babel. These do not reach the sleeper, and still the serene silver lights march noiselessly on.

An under-current of sound, a diapason to the whole wild organ fugue which the living world without is giving reverberating utterance to—harsh dissonant, discordant—add, also, the roar, the rattle, the thunder of ten thousand rolling vehicles generating discords of every imaginable nature, of every grating kind—anything but harmony and accord—yet by some marvellous fusion, the whole is toned down, and blended into a rhythmic harmony—I know not how—and as I stand in that death-chamber, it seems to change, by gliding transitions, into a tender, sobbing, mourning threnos; and I kneel and pray, and my tears fall on those cold, cold cheek: for –for—I knew her when a tender little child—oh! Kate! Kate!—or, stay, was it some other Kate I knew?

The night is growing older and colder, and solemn moaning are in the air. There are sign of vitality below stairs from those that have been dozing hourly for the afternoon Mother Needham’s strepitous voice is heard, reaching the up-stairs chambers.

"Come girl! come down to the parlour! Here are fresh visitors. Plague on’t, I’m hipped to death. Come along, my gay wenches, I have opened a fresh supply of aqua vitæ." And so they drink to drown their sorrow—to chase away the blue-devils—to raise up their spirits—to make life defiant of death; for death in the house, look you, is a very awkward customer, and it takes a good many glasses of strong waters to allay him.

Presently, Mother Midnight, with her fair-looking crew, with bare bosoms and flashing eyes—white incarnate leprosies—are becoming fast their own riotous, jovial, reckless, Bacchanal selves again! The syrens here come from their hidden caves—from their half-devoured carcasses and badly picked bones—to sit on the banks, to play with their yellow locks, to sing—what? There are no such words in Hesiod, nor in Homer, nor in Ovid, nor in any nymphs are modern inventions, so they sing--I care not to know what. But the beguiled ones enter, the gallants throng in, the "men about town" are there; and they are growing noisy, and jolly, and amorous; but into that garret there enters nothing save the holy lights of heaven, serene and tranquil; and the slumber of the sleeper is not broken.

The wild, ribald songs of the Bacchantes strike on the ear; their choruses are lugubrious as the choruses of some demon opera—say the familiars of Zamiel: ever mingling with this, with these also, through the interweaving hours of the busy night, is the cry of the new-born—the last moan of the moribund—the joyous carol of gratulation—the dreadful litanies for those passing away—life and death—death and life; and the awful harlequinade goes busily, untrestingly, untiringly on.. And so on, for ever and for ever.

The cold daybreak falls upon the calm sleeping face. It has not changed, stirred, moved. It is no one. It is nothing. It is a corpse. That means "earth to earth"—like to like—nothing more—nothing less.

Now comes the coffin, and the mourners. Oh me! what mourners. and what draughts of reeking consolation do they drink over that despised shell—a shell within a shell.

Let her go. Let her be carried tither. Little does it matter the foul nook into which she is thrust. She will sleep with good and better, and many worse than ever she was. Let us be thankful that she is at peace, that she can sin no more, and fear no more deadly stress arising from houselessness and friendlessness—dread no more the compulsory downward course arising from cold and hunger.

No. She can sin no more. And after life’s fitful fever she sleeps well; and may the Great Father look pityingly upon her, and upon us all, I pray. Amen! (113-115).

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 6: Finger

View this detail in copper here.

The woman is weeping, but the source of her grief is not Moll’s demise but rather a wart on her finger.

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 6: Finger

Shesgreen

A weeping figure shows a disordered finger to a companion who seems more curious than sympathetic (23).

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 6: Finger

Paulson, Hogarth's Graphic Works

The girl looking into the coffin is doubtless regarding Moll as a momento mori. The woman behind her is weeping because of her finger, which appears to be diseased in some way (149).

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 6: Finger

Lichtenberg

Immediately after that first mixed couple come the four unmixed ones, one after the other, if we go from the left wing towards the right; the first of them represents an inspection. Both members are, as we see, of slightly more than middle age. In both can be observed a praiseworthy and most reasonable economy of bosom, with which the young, thoughtless vermin here are not yet willing to conform. One of them seems already of an age when spectacles can be mislaid. As we see, they are needed here. The second, a lean sufferer, has something between the fingers which seems to cause her pain and which is being examined by the first with surgical, serious, and really expert touch and subtlety. What could that be? Or is it perhaps nothing at all, and only signifies something? To be frank, we almost suspect here (Greek may do it) deep esoteric wantonness under a completely esoteric mask, about which, of course, one is free to say what one likes. Oh! how agreeable it is for a commentator if he can slink away from a difficult passage to which he has merely opened the door for the reader, without saying anything more than a few conjuring words in Greek. The sufferer has warts on her fingers and, as is well known, the dead know better how to remove warts than the living. The lady without spectacles seems to think only of ways and means of bringing a wart between the fingers in contact with the corpse. The problem is not easy. If the nose will not do it, nothing else will. This makes the poor creature cry. But only think what a rogue our artist is, even in his disguises. He conceals a wanton thought and the concealment itself is again an act of wantonness, deep too but more comprehensible than the first, though quite unconnected with it. I have heard of a type of politics, deep and unfathomable, being disguised as another, also deep but fathomable, and unconnected with the first (newspaper politics), but I never heard of this sort of satire. The wart-remover, who is in charge of the operation here, has two of them herself, but on her brows like horns sprouting. Having brought the interpretation as far as this, the moral becomes easier and easier, which is evidently that of the beam and the mote and the brother's eye (72-73).

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 6: Undertaker

Lichtenberg

Next to this Patagonia face, which is one of the unattached, we see the first of the couples, of European-London culture. Mr Undertaker, who is helping one of the nuns to don her mourning-glove, makes use of that favourable opportunity to submit to her a little request of easily understandable tenor, and he does so with such good manners and with so much modest fervour that it cannot possibly remain without response. In fact, there is already something like the reflex of a gracious permission in the very eye of the supplicant, although the sign by which it was granted is not disclosed. But his assistance in putting on the glove was probably given in the form of a question, and thereby gave opportunity for a reply which, however, had to remain invisible. The contrast in these two faces is capital: the undertaker has no other design but what eye and mouth betray, he is utterly concentrated and as one-sided as possible-for the moment, at least; the girl's eye on the other hand speaks of all-sidedness and design. However dim it may seem, it certainly is not only the Spiritus rector of this assembly which is dimming it; there is play-acting here which would betray itself by the obvious traces of a triumphant smile at the blindness of the poor trapped devil to anybody who does not happen to be that poor devil himself. Drury Laneites do not forget themselves. With them every movement, no matter how small, is meant not only for the hearts which they openly attack, but, at least secretly, for their handkerchiefs as well. No sooner does the harpy learn with the surface of her right arm that the heart is full, than she already begins stealing with her left. This is the so-called small souvenir from Mr Undertaker; the big one will follow suit (71-72).

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 6: Priest

Shesgreen

Their spiritual leader, the clergyman (identified by Hogarth as "the famous Couple-Beggar in The Fleet"), who is supposed to give a religious tone to the event, has his hand up the skirt of the girl beside him. His venereal preoccupation causes him to spill. The fact of the girl who covers his exploring hand with a mourning hat is filled with a look of dreamy satisfaction (23).

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 6: Priest

Paulson, Hogarth's Graphic Works

The ribbons on his [Moll's son] and the parson's hats are weepers.

The parson is using his hat to conceal what his right hand is up to, but in his concentration he spills his Nantz (brandy).

In the copy published by Bowles the parson is labeled 'A' and is explained as 'The famous Couple-Beggar in The Fleet, a wretch who there screens himself from the justice due to his villainies, and daily repeats them'-i.e. he celebrates clandestine or irregular marriages. He has also been identified as 'Orator' Henley, but so has ever disreputable person in Hogarth's oeuvre (and this parson resembles Henley much less than the parson in Midnight Modern Conversation, Plate 134). The woman with whom he dallies has been tenuously connected with Elizabeth Adams, who was hanged in January 1737/38 (149).

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 6: Priest

Quennell

The clergyman, who will conduct the funeral,, so the portrait of a "Fleet Chaplain," a shady cleric established in the purlieus the gaol, who earned his keep by the celebration of clandestine or irregular weddings, A soft, slippery, sheep-faced man, whose dull prominent eyes, which goggle straight ahead, are beginning to brim over with a vague concupiscence, he spills his flask of gin into his lap, while his fingers make tentative explorations among his neighbour's petticoats. She does not repulse, but pretends to ignore his sally, attempting, however, to conceal it behind the wide brim of his mourning-hat (100).

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 6: Priest

Lichtenberg

The man beside her is not a clergyman. We beg our readers most earnestly not to entertain such a thought; anything like that would necessarily be prejudicial to the artist, and thereby the whole impression which this piece should make would be lost. There is merely a clergyman's frock. The thing inside it here is one of the few eminent scoundrels to whom Hogarth has justly accorded an infamous immortality; a Charters in his way. Would not the artist have done better, someone might ask, had he spared the cloth here as well? We regard that remark as very well founded; indeed, we are even convinced that it would have been better. But since that is how matters stand, we must hear the artist's defence as well. We undertake it with genuine pleasure and in the sure hope that he will be acquitted.

In his works Hogarth has made attacks on three occasions upon people in parsons' clothes, that is true; but that he ever attacked the profession of clergyman as such, we cannot recall. Out of these three, two are portraits of well-known people, about whose despicable character the voice of the public had already decided long before Hogarth voiced his opinion. He has thus done nothing but what every honest man had done before him, except that he drew and painted where others spoke or wrote. Whether the picture of the third is also a portrait, we cannot say with certainty, but it would still show no disparagement of an honourable calling if it were not. The fellow is only a bit of a gourmand, and on an occasion which regularly occurs but every seventh year. Apart from this he does not hide his doings in a corner, but makes his feast, so to speak, right in the lap of his constituency, before the eyes of his flock, who feast together with him, and it does not cost his family a penny. Such conduct can hardly be called reprehensible. But here, here the situation defies description. Hogarth certainly felt this very keenly. He therefore did something which he had never done in any of his works, so far as we know; something which is hardly compatible with his manner of satire (though in order to exonerate oneself completely, even such extraordinary methods may be necessary). On the 1,200 copies for subscribers, he marked that vile creature with a capital 'A' which referred to a footnote under the Plate where it is clearly stated who he was, and where and how he managed to escape the law. Now just imagine what a lawless creature that abomination must have been, when an honest, well-known and well-esteemed man like Hogarth does not scruple to draw him thus for all the world to see, and, in addition, virtually invokes justice against him. In this way, or so it seems to us, he has not only proved that he did not intend to attack the clergy's estate, but on the contrary, he has shown how much he had its honour at heart. When hunting out subjects for satire, an occupation which he tirelessly pursued, many an object that knew how to evade the activity of the police and the law fell into his snare, and he acted rightly in delivering them up to the authorities, or, if the authorities let them escape again through carelessness, in giving them at the next opportunity the coup de grâce himself.

This scoundrel, evidently the Spadille among the trumps in hearts, as the other black ace, the Undertaker, is the Basta, was so well known under the name Couple-Beggar (because he copulated for a few pence) that Hogarth's interpreters have forgotten his proper name, a feature which in itself speaks for his great eminence in the profession. We have been assured that, apart from that other occupation, he united himself regulariter a couple of times a week-with the gutter. Not only symbolically, as the Doge of Venice marries the Adriatic. Instead of throwing a trifle into it, he threw in everything which he still had left in the evening--himself. A Divine he has never been called, he was merely an adept at holding Divine Services, and even there he Just babbled through the Marriage and Funeral service-for a few pence. His spiritual hand, as it was called, never fished for more, but fished all the more often-while his worldly hand demanded stole-fees wherever they could be found, in pockets with and without bottom ad infinitum. This is well known. Whether Hogarth tried to hint at something of this sort here cannot well be decided. In his so-called spiritual hand, the left one, he holds the funeral brandy very badly and stains his handkerchief with it. Where the worldly one is, nobody, so far as we know, has yet been able to decide. People have looked for it under Couple-Beggar's hat, which the Manille is holding very carefully in front of it, but it has not been found there either. We therefore willingly abandon this locum difficillimum and pass over with genuine pleasure, in the way of commentators, to an easier one--to Snub- nose. She stands at the foot of her friend's coffin with a mortar in her hand, like a female sutler before the inn counter. I call that feeling! And yet, to the honour of human nature, there is in her wild look a kind of unmistakable disapproval at the behaviour of the neighbouring couple. It absorbs, as one can see, her whole attention, and although her mouth speaks of much latitude in such matters, yet her eye seems to find place and time and hour somewhat unbecoming. It is a fine touch of Hogarth's to put even into that unfeeling tiger-face an expression of disapproval at such bestiality, and thus to make even the stones cry out about it. In passing we would beg our readers to recall for themselves what that creature has done and suffered so far, and what sort of a life that is, and yet even as we read this, it is still lived by countless women! But we do not wish to prejudice the views to which this might give occasion about the inheritors of the Kingdom of Heaven and their spiritual guides! (74-76)

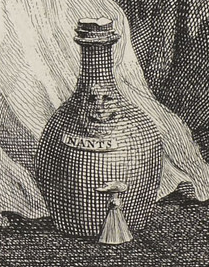

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 6: Jug

View this detail in copper here.

The jug of Nants (brandy) is obviously what is keeping this funeral crowd in such an elevated mood. Notice also the cracked glass in front of the bottle. Cracked and broken dishes, such as those from PLATE 3 and PLATE 5 are often used in Hogarth, as in Pope, to demonstrate a loss of innocence and a "fall" into illicit sexuality.

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 6: Jug

Lichtenberg

What strikes the eye immediately here is the big gun which has been posted at the flank. If compared but perfunctorily with the figure sitting beside it, it could easily be taken for a tear-bottle, but for this the shape has obviously far too much of the mortar and howitzer. It is really a drinking gun, a six-pounder at least, loaded with Nants (French liqueur). Very peaceful and merely serving the function of bonfire and fireworks for the column. The counterpart, a small mortar, is to be found near the right wing upon the coffin-lid, and for the same purpose. This fire from the wings, as we shall see, has an uncommon effect upon the centre. The moment has been excellently chosen by the artist. It is, in effect, the moment when age exalted by Nants approaches the feelings of youth, and when the gathering resembles the beautiful picture of the snake which with tail in mouth coils itself into a circle, to which everything perfect in the world must eventually more or less conform. It will stay like that-provided the hearse is not too long in coming and the coffin does not lose through the delay the respect due to it. But let us now examine a little closer how things stand.

The artillery is well served. The small mortar is taken charge of by the snub-nose whom we already know, and the howitzer by the fire-toad who in the corner there wrings both her fore legs and stretches out a hind leg (70).

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 6: Son

View this detail in copper here.

The central figure, Moll's son, further underscores the fact that Hogarth is not specifically blaming her. Uglow notes, "One sign of Hogarth's respect and compassion toward Moll in 'The Harlot's Progress' is that she kept her child alive, and even when she herself was dying in squalor, her boy was fed and stoutly clothed" (326). Unlike the Sqanderfield offspring from Marriage à la Mode, this young boy shows no sign of the syphilis which killed his mother and has almost certainly affected him. I see no real signs, then, in this series, and especially not in this plate, that Hogarth indicts her as complicit in her own ruin.

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 6: Son

Paulson, Hogarth's Graphic Works

The chief mourner is the little boy, the Harlot's son, with his large black felt hat edged in broad lace. The ribbons on his and the parson's hats are weepers. The boy is unconcernedly winding up a peg-top (or "castle-top," as some of the versified descriptions of the print call it) (149).

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 6: Son

Uglow

The little boy, in full adult gear, with lace around his black felt hat, examines his spinning-top oblivious to the fuss, a study in absorbed concentration from his open mouth to his feet, dangling down in their buckled shoes (209).

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 6: Son

Quennell

Near the sprigs of rosemary arranged on a platter, the chief mourner sits swaddled in his weeds and, being a philosophic and much-experienced child, devotes his attention to his brand-new spinning top. Hogarth's sympathy with the characters of children clearly extended to an appreciation of their intermittent callousness; or, rather, he would seem to have understood what narrow and arbitrary limits confine their powers of suffering. But at least the child's indifference is a form of innocence . . .(99-100).

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 6: Son

Lichtenberg

Almost beneath the coffin, just as formerly beside the death-chair, sits again the little heir, occupied with a pain-alleviating instrument. There it was a chop which he turned on the spit; here he winds a top which he is going to spin in the chamber of mourning. It looks as if the anodyne had worked well on the little chap. However, it may also be that what one takes for the cause here is really the effect. The boy does not grieve, but not because he is roasting his meat and winding his top, but he roasts and winds because he does not grieve. Why should he fret? Just as he has no father, since nobody knew who he was, so he had no mother either, because in the society where he lived nobody had time to be one. Oh, the words father and mother mean very much more than we usually find in their dictionary definitions, and more than people think when they read them! Just as many a child whose true parents are far beyond the grave finds, thank God!, a new father or a mother, so, alas! there are fatherless and motherless orphans whose parents are thoroughly enjoying themselves day after day. Evidently the poor fellow has often been pushed from one corner into another; but since the decease there will be one pusher less. Even supposing that snub-nose will sometimes throw him into the corner now, there is still nobody near at hand to throw him back again. From the boy's puny legs we might almost conclude that the anodyne necklaces have not been of much use. That Hogarth has dressed the boy up as chief mourner is a mockery in more than one respect; children are never used in that role; it must always be a man of some presence who would not disgrace an afflicted heart. But the expression could also imply ''the chief among the mourners', and in this way the situation becomes almost ludicrous. For if the most deeply afflicted is winding his top shortly before the cortège leaves, we can easily surmise how deeply afflicted the others must be. The dish with rosemary as well as the little table with the gloves and the glove-stretcher for the too-narrow fingers are plain enough, but the position of the pair of gloves is perhaps not without intention. They seem to have moved apart as if shocked, and so as to clasp each other again, and to shame by their example at least ten pairs of hands of flesh and blood among the thirteen which are assembled here and are occupied in a somewhat worldly manner (77-78).

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 6: Lady

Uglow

Scene by scene, from the open air of the coachyard Hogarth tracked his heroine's increasing confinement down to her last tight space, her coffin. One young woman looks at her face, hidden from us. Around this gesture of pity and, perhaps identification, women stand in extravagant stage poses of grief (209).

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 6: Lady

Ireland

The female who is gazing at the corpse displays some marks of concern, and feels a momentary compunction at viewing the melancholy scene before her: but if any other part of the company are in a degree affected, it is mere maudlin sorrow, kept up by glasses of strong liquor (118).

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 6: Lady

Lichtenberg

One of the members of the sixth and last couple, the living one engaged in contemplation of the dead, Hogarth has not put for nothing into the centre of the picture. He wants us to take special note of her. Just as she is at the apex of the semi-circle formed by the assembly, where the two wings converge, so also converge in her role the moral lines which the artist here wishes to draw. That is why the girl is also one of Hogarth's beauties. This is a point to remember, for it might pass unnoticed. Moreover, the girl is not altogether bad. Youth and freshness are there at least, and to these qualities is addressed the moral which can best be expressed by the words from the coffin:

What thou art and how thou art, I was too but a short while ago. Abandon the path thou art treading; if not, think of this: what I am now, thou too shalt be, and in a short while.

Whether the little goose has heeded these words, cannot be ascertained from her face; but that, if she has heard them, she will have forgotten them even before the hearse arrives, this I think can be predicted with certainty (76-77).

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 6: Mirror

View this detail in copper here.

A narcissistic mourner pays more attention to her reflection in the mirror than the woman who is being waked.

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 6: Mirror

Shesgreen

At the mirror a girl adjusts her headgear vainly, oblivious to the prominent disease spot on her forehead. (23).

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 6: Mirror

Ireland

One of them is engaged in the double trade of seduction and thievery; a second is contemplating her own face in a mirror (118).

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 6: Mirror

Lichtenberg

Behind that pair stands the third; a pious sister in conversation with another, who shall have no name, in the mirror. Undoubtedly the happiest couple of them all. In every combination by pairing in this world, a certain compensation of defects and accomplishments in the subjects is necessary if the common happiness is to be lasting. What you lack, I have, and what I lack, you have, is the firmest foundation. But in the combination of which we are speaking here, that is quite unnecessary, and for complete satisfaction it is quite sufficient if only one of the members either has every possible accomplishment or, what amounts to the same thing, believes she has them. Thus in our case the girl who presents her back to us is young, and beautiful, or at least she thinks so herself; now if this is granted she need not care a jot about the characteristics of the other, and yet only see with what loving admiration they gaze at each other; like two angels who pass and do not know one another. Each sees in the other a higher creature, each admires and is admired, each bends the knee and the scene ends in mutual adoration (73).

A Harlot's Progress: Plate 6: Coffinplate

View this detail in copper here.

Some commentators have noted that the coffin-plate merely identifies Moll as "M" (as does her suitcase in PLATE ONE) and that later viewers have assumed that she was Moll--a decidedly popular name for literary prostitutes. However, Trusler insists on calling her "Kate" and Ireland identifies her as "Mary."