How to Read Hogarth

“Reading” a Hogarth narrative picture series can be assisted by the number of excellent commentaries, many of them available on this site. One of the best modern examples especially friendly to beginners is Sean Shesgreen’s Engravings by Hogarth: 101 Prints, published by Dover. However, any careful reader can trace the development of story in Hogarth’s work by realizing that the engravings are the visual realization of the elements typically discussed when analyzing any narrative.

Hogarth is widely regarded as an innovator in the use of plot in his picture series. While he was not the first to publish narrative in this form, critics such as Shesgreen credit him with being the one of the first to do so in a “skillful manner” not completely allegorical in nature (xv). Shesgreen further notes that Hogarth’s plots are not episodic as common in the picaresque tales popular in the period (xvi). Rather, he makes effective use of cause-and-effect plotting, carefully showing how each event is a direct result of the one that preceded it. The Four Times of the Day seems to be an interesting exception to this rule, but even in these plates the final work is a chaotic culmination of the problems exposed in the previous ones with the social and domestic divisions prominently displayed being realized ultimately in utter anarchy: false piety and poverty in the first; affectation and snobbery versus graphic public displays of a range of emotion (from lust to frustration) in the second; a reversal of male and female roles in the third. By the final plate, then, the lack of happy medium has completely eroded all semblance of social order.

Other series develop their plots more typically. An excellent example of Hogarth’s more direct cause-effect plotting is The Four Stages of Cruelty where Tom Nero begins his career in crime by torturing animals while a charity school boy. In the second plate, he moves from dogs to horses as a coach driver, beating his horse for buckling under the weight of a heavy passenger load. His ultimate act of cruelty occurs when he murders his pregnant lover, hacking and mutilating her corpse in a way reminiscent of the way he has consistently treated his animal victims. The series finally concludes with Tom himself being (deservedly?) brutalized upon the anatomists’ table, his heart being devoured by a dog taking revenge for the actions in the first plate.

Hogarth’s “progresses” also depend upon this structure to relate their tales. A Rake’s Progress begins with a young man inheriting his miserly father’s estate. However, all is not as it seems. His has already engaged in questionable behavior, having broken a young girl’s heart, possibly even impregnated her, and she brings her mother to accuse him. His lack of experience with wealth causes him to turn his back on the lawyer who robs him. When the rake surrounds himself with the opportunistic, sycophantic array of hangers-on in the second plate, it is no surprise. His already-compromised morality is further degraded in the third plate as he becomes the emblem of drunken over-indulgence. Yet his naivety remains intact; a prostitute steals his watch just as the lawyer claimed a share in the first plate. His vices soon erode his inheritance, and he is arrested for debt in the streets. In an attempt to redeem himself financially, he is compelled to marry a rich widow. However, lessons remain unlearned, and this new wealth is spent as quickly as the old, with Tom back in the taverns. A stay in debtors’ prison follows, and Tom, out of options, descends into madness and into Bedlam, where he becomes the object of curiosity seekers. The assembled lunatics recall the fashionable entourage of the second plate, and it is clear how far he has fallen.

While Hogarth’s plots usually follow an easily discernible pattern, understanding characters presents more of a challenge for the uninitiated. However, the engraver frequently leaves a number of clues regarding their identities, traits and values.

Careful examination of the plates will often reveal a protagonist’s identity. Tom Nero is identified through an eerily prophetic hangman being sketched by a schoolboy in the first plate of The Four Stages of Cruelty.

Tom’s fate is predicted in this scene from A Rake’s Progress, plate 1.

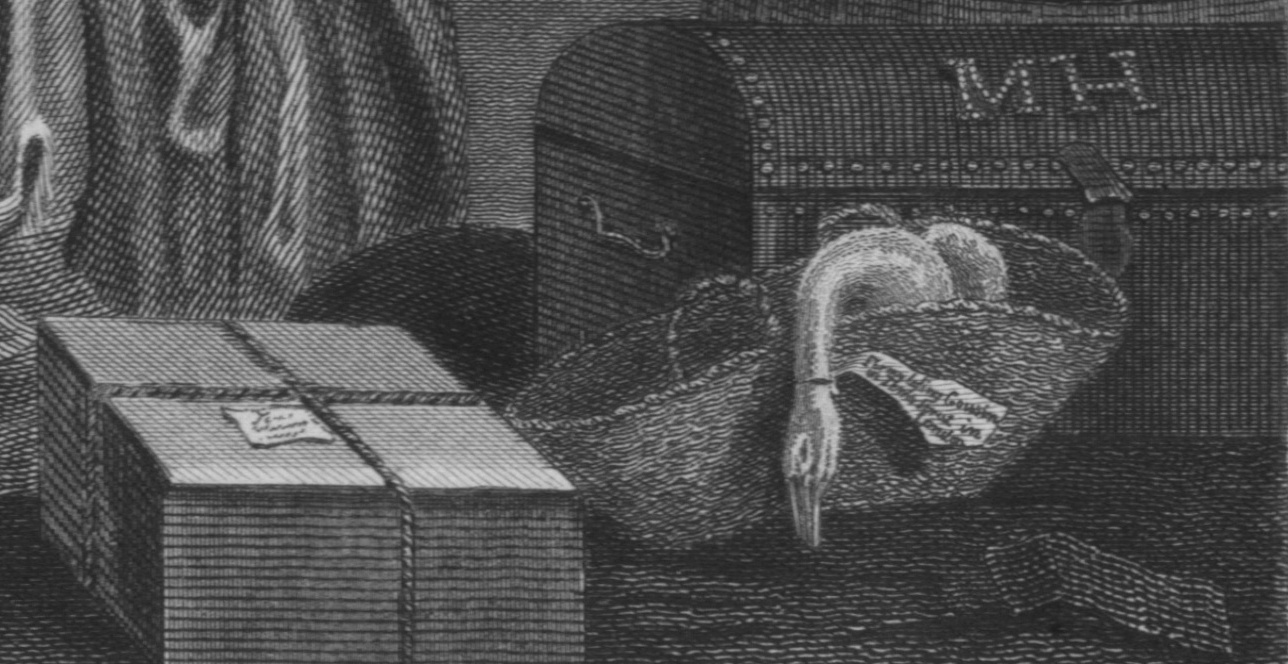

Moll Hackabout’s identity is a little trickier to ascertain. Her initials are featured prominently on her luggage in the first plate of A Harlot’s Progress, but it is not until the last plate when that she is identified, through her coffin’s inscription, as M. Hackabout, dead at twenty three. “M.”, as many commentators have noted, could just as easily have been “Mary,” but “Moll,” slang for “prostitute” has persisted.

Moll’s portmanteau reveals her initials to be “M.H.”

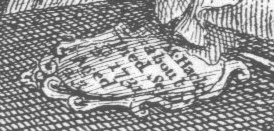

Moll’s coffin inscription from the concluding plate of A Harlot’s Progress. It reads, “M. Hackabout Died Sepr 2d 1731 Aged 23.”

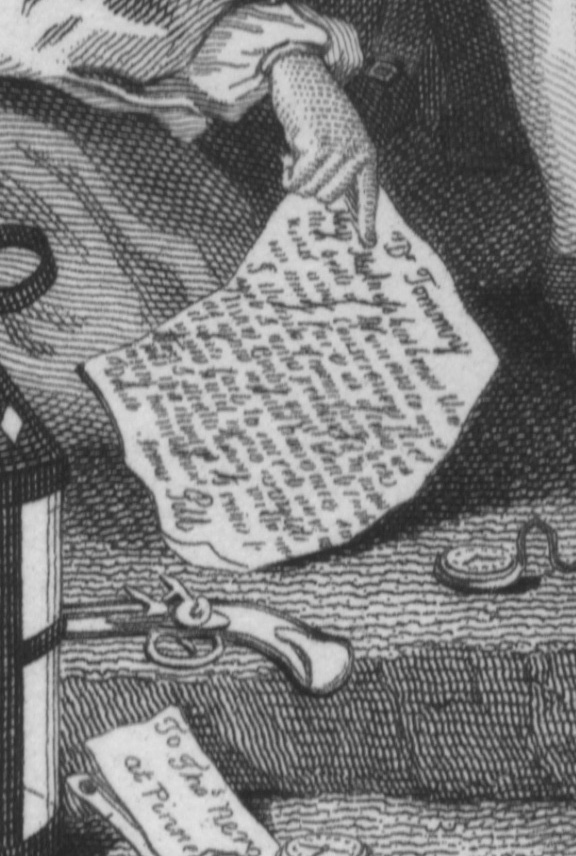

The doomed Ann Gill from The Four Stages of Cruelty reveals her identity and her intentions in a signed letter to her lover (and killer) Tom Nero. The letter underscores the tragedy and

Ann’s Letter to Tom from The Four Stages of Cruelty, plate 3. It reads, “My mistress has been the best of women to me, and my conscience flies in my face as often as I think of wronging her; yet I am resolved to venture body and soul to do as you would have me, so do not fail to meet me as you said you would, for I shall bring along with me all the things I can lay my hands on. So no more at present; but I remain yours till death. ANN GILL”

viciousness of her murder, showing that she has robbed her mistress against her better nature, admitting, “my Conscience flies in my face as often as I think of wronging her” but that she, blinded by love and compromised by her pregnancy, remains ironically Tom’s “till Death.”

Hogarth’s contemporary audiences had a distinct advantage in identifying some characters, as he was fond of including noted figures. To these viewers, the bawd from the first scene of Harlot was not simply an anonymous example of the corruption offered by London; she was easily recognized as Mother Needham, a famous procuress. The man lurking in the shadows awaiting the services of the newly employed Moll Hackabout was identifiable as Colonel Charteris, an infamous rake and rapist who symbolized the destructive wanton decadence of the upper classes. Harlot also features representations of highwayman James Dalton (or at least his wig box) and harlot-hunter John Gonson.

Mother Needham assesses the merchandise. The real-life Needham died in 1731, the most famous procuress of her time.

Sometimes the famous figure can be used thematically, as in the final scene from The Four Times of the Day. Hogarth’s audiences would have recognized Sir Thomas de Veil, here pictured as a drunken freemason being helped home. The theme of hypocrisy, seen in the first scene’s falsely pious woman who refuses to help the poor as she haughtily makes her way to church, is again invoked. The real de Veil was a magistrate who waged a campaign to quell London vice; Hogarth suggests that de Veil was himself a participant in the very behavior he attempted to stop in others. However, the artist has the last laugh; a full chamberpot is emptied, and Hogarth cleverly manipulates the visual space so that is appears that the contents are practically raining down upon the drunk’s head--a final word on the ridiculousness of false morality.

Sir Thomas de Veil from Four Times of the Day. de Veil decried vice, but his drunken state here reveals his hypocrisy.

Shesgreen comments that Hogarth’s use of the pre-Dickensian working-class protagonist merges the allegorical Everyman characters (with names like Rakewell, Goodchild, Silvertongue) with the real streets of eighteenth-century London through this use of recognizable figures. Though he comments that Hogarth is never “overly taxonomic” in his use of these universalized fictional characters, the addition of celebrities lends even more realism to his message (xvii). The use of contemporary images is unfortunately lost on some modern audiences.

Without understanding the intricacies of eighteenth-century clothing, a viewer can still comprehend the relationship of a character’s dress to his or her personality. Moll, for example, begins as a simple country girl, moves quickly to a fashionable kept mistress in the second plate, and then to a common Drury Lane whore in the third.

Arriving at London, she is fully dressed, a sweet rose obscuring her covered bosom. The further she falls, the more she reveals. In the second plate, she flashes her keeper to allow her lover to escape. In the third, she dangles a watch suggestively near her exposed breast, looking suggestively at the viewer as if to reveal exactly how she manages to procure this merchandise. This is the height of her undress. The next plates gradually cover her back up. The fourth features her proudly fashionable among the mocking hemp beaters. The fifth wraps her up in sweating cloths in an attempt to cure her syphilis. By the last plate, she is completely encased in her coffin. Moll cannot reveal herself so wantonly without suffering consequences. In this case, her punishment is the eventual eroding of her body both through syphilis and through Hogarth’s attempts to re-cover her. Her dress throughout the series traces her acquisition and loss of sexual power.

Marriage à la Mode’s Lady Squanderfield is transformed from a slumping, uninterested, plain middle-class nobody in the first plate into a fashionable adulteress, fully realized in the fourth plate. The images parallel each other, as her aping of aristocratic dress parallels her adoption of high-class decadence. Her carefully covered bosom in the first plate yields to cleavage in the fourth. Her modestly covered head is now curled by a French hairdresser.

Hogarth also cleverly uses background objects to reveal thematic concerns, to mock characters’ pretentiousness and to warn the audience of impending danger. Any “reader” of Hogarth must pay very close attention to what the artist has placed around the rooms and in the streets, as these items are essential to understanding the complete message of the plates. Most Hogarthian interiors have paintings on the wall; these pictures figure heavily in the narrative. A Rake’s Progress opens with the young Rakewell inheriting his father’s fortune. The portrait of the elder Rakewell underscores his miserliness by showing him counting his money. His only other “work of art” is a coat of arms composed of a vice (pun intended) with the warning “Beware.” The two extremes implied in the art—the hoarding father and the foreshadowed decadence—are both problematic.

Lady Squanderfield’s father displays the kind of social climbing that compromised the admirable qualities of the middle class. When his daughter returns home, her lover and husband both dead, the interior of his home is finally revealed. In addition to the extreme miserliness displayed most prominently in the starvation of his dog, his taste in art is abysmal. His walls are covered with parodies of Dutch painting, mocking what Hogarth believed to be the vulgarity of that particular art movement and equating them with the questionable morals of a father who would prostitute his daughter for social gain. For Hogarth, one of the clearest signs of compromised morals is bad taste in art. Shesgreen also observes that art in Hogarth is also an indicator of social class, that “aristocrats possess sublime history paintings of mythological topics purchased abroad” while the impoverished, like Moll in her final state, tend to dwell in “underfurnished” rooms (xxi).

In addition to the art on the walls, Hogarth places other important objects in his plates. In A Harlot’s Progress, Moll’s syphilis cures have proven ineffective, and her two doctors appear more concerned with bickering with each other than with attending her. To underscore the quackery, her teeth, which have fallen out as a side effect of one of her “cures,” are symbolically placed on a prescription issued by Dr. Rock.

Plate 5 of Marriage à la Mode features the death of Lord Squanderfield and the escape of his murderer. Silvertongue’s status as the lover of Lady Squanderfield is made obvious not only by his state of undress but also by the masquerade masks which lie discarded on the floor. Long believed by moralists to be dens of immorality, the masquerade cements itself here as the enticement to illicit sex. Lady Squanderfield’s enjoyment of all that is problematically depraved about the upper classes is complete.

The Squanderfields had already displayed that money does not bring refinement in their preference for tacky artifacts which Hogarth sprinkles throughout the series, first cluttering the mantelpiece in the second plate (highlighted by a particularly atrocious clock) and later scattered about the floor in the fourth. A servant uses one of these examples of poor taste and points at the horns of a statue of Actaeon to reveal another reality in the series—the cuckolding of Lord Squanderfield.

As was true with the paintings discussed above, a tendency toward tackiness in décor unfailingly indicates immorality. Hogarth’s similar dislike for opera does not bode well for how the art form is portrayed in his work, and he makes the newly rich Lady Squanderfield and Tom Rakewell opera fans as a testament to their lack of taste.

Hogarth frequently uses dogs and other animals in his works, often as symbols. Moll’s monkey in plate 2 is frivolously fashionable. Her cat in plate 3 provokes curiosity as to what lurks under the bed. Tom Nero’s abused horse inspires audience sympathy. Hogarth’s favorite animal, however, is clearly the dog. Canines appear in almost every series. Rakewell’s union to a much older woman in plate 5 of Rake is parodied by the two dogs in the plate which hilariously represent the newly betrothed. Similarly, in the first plate of Marriage, two dogs are yoked together in emulation of the forced union of the young couple. A mad dog reflects the growing insanity and chaos in the sixth plate of A Rake’s Progress. A dog gets revenge, eating the disembodied heart of Tom Nero, justly rewarding Nero’s torment of a dog in the first plate of Four Stages of Cruelty.

Shesgreen comments that Hogarth’s settings are a marriage of the literal and symbolic (xxi). White’s Gambling House, the setting of plate 6 of Rake’s Progress, is threatened by fire in the engraving; the real White’s had burned in 1733. The historical reality behind the artistic representation adds urgency and finality to Tom’s fall; he is about to go up in flames. Plate 4 of The Four Times of the Day is set before the statue of Charles I in Charing Cross. The chaos realized here could be as real as the setting, Hogarth warns, with London’s real leaders as powerless to prevent it as Charles is in the plate.

Hogarth combines all of these narrative elements in his engravings, and the skilled “reader” of his work will do what any sophisticated student of literature or film will do: carefully observe and scrutinize every detail, analyzing its place in the web of the tale. Using plot, symbol, character and setting in purely visual ways, Hogarth tells complex stories that reach beyond the allegorical morality tales common to past picture series, legitimizing sequential engravings as an effective storytelling medium.