Marriage a la Mode: Plate 4

1745

13 13/16” X 17 5/8” (H X W)

Engraved and etched from Hogarth's painting.

View the full resolution plate here.

View the painting here.

In this scene, the new countess, also being styled is “educated” by Silvertongue, the lawyer who will soon be (if he is not already) her lover. Silvertongue instructs the girl, not in Latin or rhetoric, but in the use of her body. Plate 4 features an interesting crowd in the Lady’s chambers: a pompous castrato (foreshadowing the emasculation of husband and lover in the next scene) with his admiring fan, a flute player and hairdresser—all demonstrating a fear of feminizing influences. When the husband is away, the solid English home is infiltrated by effeminate foreigners. The cuckolding of the husband is underscored by the servant pointing at the horns of a tacky statue that the Countess has purchased at an auction.

Paulson comments that the bride has “already been taught the way of the world by her father” (Life vol. 1 484) but it is more likely that this task will be accomplished by the lawyer. Silvertongue is instructing the young countess on the art of deception using her body; he’s also inviting her to that most depraved of activities—a masquerade. His portrait stares down from the wall, highlighting his prominence in the private life of the Countess.

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 4

Shesgreen, Sean. Engravings by Hogarth. (1973)

Having cast off her middle-class awkwardness and inhibition, the Countess imitates the life style of the aristocracy (the coronets about the room indicate that the old Earl is dead). In contrast to her husband’s bizarre passion for young girls, the Countess’s middle-class origins reveal themselves in her interest in an ordinary live affair. Wearing jewelry on her hair and fingers and dressed in a low-cut gown, she sits at her levee with her back to her guests, oblivious to the music, attentive only to the addresses of Silvertongue. A child’s rattle on her chair reveals that she has a baby which she has the servants care for.

Looking very much at home, Silvertongue lolls on the couch beside her, leaning intimately toward her. He points to the screen behind him and, as he explicates the masquerade scene on it, arranges an assignation for the night. The paper in his hand reading “1st Door,” “2 d Door,” “3 d Door” is a key to the screen. Beside him lies “Sopha,” a venereal novel by Crébillon. The art in the room comments on the lady’s preoccupation. Above her are pictures of Lot’s daughters preparing to seduce their father and Jupiter possessing Io. On the opposite wall hang a version of the rape of Ganymede and a portrait of Silvertongue himself. Before them a black boy plays with a group of tasteless art objects purchased by the lady at an auction. A book beside them reads “A Catalogue of the Entire Collection of the Late Sr. Timy. Babyhouse to be Sold by Auction.” The lot includes a tray inscribed with an erotic version of Leda and the swan by “Julio Romano” and a statuette of Actaeon; the boy points to Actaeon’s horns to interpret the import of the conversation behind him.

Lying on the floor across from the youth are playing cards and correspondence, both indicative of the Countess’s social life. “Ly Squanders Com is desir’d at Lady Townlys Drum Munday Next”; “Lady Squanders Company is desir’d at Miss Hairbrains Rout”; “Lady Squanders Com is desir’d at Lady Heathans Drum Major on next Sunday”; “Count Basset begs to no how Lade Squander Sleapt last nite.” The spelling in these notes is a judgment upon their authors’ literacy.

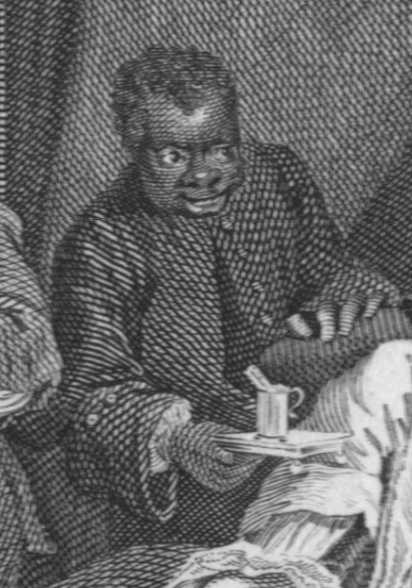

Most of the group sit around in strained, affected poses. The center of focus is a bloated castrato (probably Francesco Bernardi, an Italian singer who lived in England for a while). Overdressed in gold lace and tastelessly bedecked with jewels, the vain fellow sits haughtily back in his chair, unaware that only two in the whole group listen to him. Next to the singer sits a man with his hair in papers, bored but formally attentive. Beside him a fellow gestures preciously and screws his face up in feigned appreciation. A man with a riding whip snores while his wife strains ostentatiously forward in the direction of the castrato. A black servant laughs at the scene (54).

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 4

Uglow, Jenny. Hogarth: A Life and a World. (1997)

The magic that his wife succumbs to is more frivolous. Hogarth paints her in her bedchamber receiving guests at her toilette---a much derided habit imported from France. The coronets over her pink-canopied bed (its open curtains a salacious female invitation), and over her gilt mirror, declare that her husband is now an Earl; the little coral rattle hanging from her chair tells us that she has a child, making the disease of the previous scene more ominous still. Neither change in status, to mother or to Countess, has had a sobering effect. She tosses a cloth across her shoulders to protect her yellow satin while the French valet curls her hair. A lolling Italian castrato flashes his presents of diamond rings and ear-rings as he sings to the music of a German flautist. A fop in curl-papers points his toe and sips his chocolate, an exaggeratedly over-perfect illustration from Lairesse, who specified that it was correct to hold things lightly and 'in appropriate instances to extend one's little finger elegantly'. A rapturous woman spreads out her arms--an acceptable display of aesthetic 'sensibility', not vulgar personal feeling. Behind her the handsome black servant, smiling, hovers with her cup, while her country-squire husband yawns in the corner next to a fan-holding man- about-town. The scene looks silly but harmless--yet it will prove just as fatal as the quack's chicanery. The music and the fallen cards on one side of the room are balanced on the other by the little slave in Moorish dress, who grins and points at the antler horns of Actaeon, changed into a stag for watching Diana bathe naked. Behind him the Countess's lover, the lawyer Silvertongue, gestures eagerly towards the screen with its picture of a masquerade: the tickets are already in his hands.

Hogarth's wit had never been so assured. Each scene had a different kind of humour. The marriage contract, like the opening of a comedy of manners, introduced formal contrasts of class; the bourgeois and the aristocrat conform to convention - the Alderman stooping, feet wide apart, the Earl lying back with a pseudo-Watteauesque grace. The morning scene, so acute and penetrating in its psychological study of the young couple, damned both the idle rich and the doom-demanding Methodist servant. The consulting room wove the darkness of Jonson's Alchemist into a satire on modern doctors. The brilliant, billowing lines of the morning levee blended the comedy of intrigue with a stab at 'effeminate' artifice of culture. In these early scenes the dance of the eye is lilting, but now the tempo changes. All along, the harmonies of Hogarth's painting have included a sombre note, a hum of warning. Despite Fielding's praise of his 'force of humour' Hogarth often tips towards tragedy. In stage comedy, characters often overcome obstacles and find happiness; even in the plays of Jonson or Molière, which end with the exposure and punishment of frauds, the world is returned to some promise of order. But there is no happy resolution for Moll Hackabout or Tom Rakewell, or for the new Earl and his Countess. Instead, after an illusory whirl of excitement, they slide down a bleak declining curve (379-381).

Most details carry sexual innuendoes. . . At the levee, a copy of Crebillon’s La Sopha, a shocking licentious novel (in which a sofa described what happens on it) lies next to Silvertongue; this was translated into English in 1742 and is just the sort of book the Countess would have read. French modishness here goes hand in hand with freedom from “polite” restraint and makes one look afresh at the black servant; Crebillon’s heroines enjoy liaisons with “Negroes”, who “are capable of giving way to all the Fury of Vigorous Desire”, and know “the most hidden mysteries of love”. An even clever pointer to the Countess’s adulterous giddiness is the image of Leda and he Swan on the dish in the page-boy’s basket, a motif from the pornographic prints of Giulio Romano. On the walls hang three “Correggios”—a Rape of Ganymede very obviously positioned above the head of the fop, a sexy Jupiter and Io and Lot and his Daughters—and a portrait of her lover. The clutter of objects from the auction, still with their tickets on, leads our eye to the figurine of Actaeon, while a strong diagonal runs across the page-boy’s grin implicating the cuckolding couple and his pointed finger suggesting that the fop is as ridiculous, and “unnatural”, as the statue (384-385).

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 4

Paulson, Ronald. Popular and Polite Art in the Age of Hogarth. (1979)

The fourth scene is the crucial one, by which time the family has split into separate fragments, the old earl is dead, his son off with a mistress, and the new countess appears with her lover, a lawyer named Silvertongue. They are presented as vested supporters, one sejeant and the other couchant, on either side of a gloomy escutcheon. The escutcheon is her mirror, divided per bend ombre, a blank centerpiece, denoting an empty past, an empty future. (In the painting, it is divided bend sinister, presumably for reversal in the engraving,) in which the lines of shading represent heraldically gules, the color of the blood that is shed in the next scene.) The decoration beneath forms a crest with a casque, the garde visure empty and placed affrontée. The drapery around the mirror suggests a fringed and corded mantelle, the objects in the wife’s hair a coronet triumphant, and Silvertongue’s paper a ragget motto.

The whole picture emerges from this key, as the first scene did from the family tree. The auction objects, laid out directly beneath the mock escutcheon, serve as an additional, a comic heraldic motto. The sequence is virtually a summation of the six scenes of Marriage à la Mode in miniature: a round vessel and a bowl with a Rape of Leda plus an Actaeon (the horns suggesting the cuckolded status of the countess’s husband) lead to a deformed progeny, which diminishes in size until it ends in a mouse. (In the last plate, the surviving heir is crippled and deformed, with the father’s and grandfather’s patch on its neck) (43).

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 4

Paulson, Ronald. Hogarth’s Graphic Works. (1965)

The fourth plate balances the husband's life with the wife's, epitomized by her levee. She is in her boudoir, with her bed in the alcove in the background now significantly topped by an earl’s coronet: the old Earl is already dead, and his hard bargain all for nothing. The baby's rattle on the back of her chair suggests that she is now a mother and so neglecting her child J. Ireland, I , 25 n., 38. believes her shape showed her to be pregnant).

The Countess is engaged in pleasant conversation with Counsellor Silvertongue while a barber dresses her hair for the day. Silvertogue is explaining to her, with the aid of a "key," the figures on the screen behind them (pointing to a friar and a nun). The screen shows a masquerade, and the key refers to "1st Door," "2d Door," and “3rd Door.” He is arranging for them to meet at the masquerade. On the sofa lies a copy of Le Sopha ("SOPHA"), a piece of erotica by Crébillon fils (publ. 1740) in which a sofa describes the events that take place on it. Another name connected with erotica, "Julio Romano," appears, on a dish with a version of Leda and the Swan; this is in a basket among a great pile of junk, identified by a nearby volume. "A CATALOGUE of the entire Collection of the Late Sr. Timy Babyhouse to be Sold at Auction." (a pot is labeled “Lot 7"). The auction, like the masquerade, according to Rouquet’s commentary (p. 36), offered “l’occasion d’entretenir sans scandale des gens qu’on ne peut voir ailleurs." Among other things purchased at the auction is a broken statue of Actaeon with his prominent antlers, at which the negro boy points significantly.

The singer is probably the castrato mezzo-soprano Francesco Bernardi, called Senesino (1690?-1750?), who had sung with Handel until 1733 and then sang with the rival company at the King’s Theatre, Haymarket. The face, with its turned up nose bear a close resemblance to contemporary portraits of Senesino (by Goupy, engraved by Kirkall; by Hudson, engraved by Van Haecken, 1735; cf. Berenstadt, Cuzzoni, and Sensino, Plate 310). By 1735 Senesino had returned to his native Siena. Nichols, therefore, believed the singer was meant to be Giovanni Carestini (1705-c. 1758), the "finest and deepest counter-tenor that has perhaps ever been heard" (C. Burney, A General History of Music, 1789, 4, 369) brought to England by Handel in 1733 to replace Senesino. The adjacent lady in raptures has been identified as Mrs. Fox Lane afterwards Lady Bingley to whom the cry "One God, one Farinelli” is attibuted (cf. Cat. No. 133; Gen. Works, 2, 179). Her concerts, at which Mingotti performed exclusively, were of great social prominence (see Burney, 4, 467 n.). Various cards lie at the singer's feet: a five and six of diamonds and notes inscribed “Ly Squanders Com is desir'd at Lady Townly Drum Munday next,” “Lady Squanders Company is desi’d at Miss Hairbrains Rout,” “Lady Squanders Com is desir’d at Lady Heathans Drum Major on next Sunday,” and “Count Basset begs to no how Lade Sleapt last night." (A rout, drum, or drum major was a noisy assembly of fashionable people at a private house. Count Basset may be a memory of the character in the Vanbrugh-Cibber comedy, The Provok’d Husband [1727/8]; cf. also "the borough of Guzzledown" and the second Election print, Plate 218.)

The thin man next to the singer has been identified as Herr Michel Prussian envoy, and the flutist as Weidemann, a German musician. The country-type sleeping with a riding whip in his hand, may be the voluble lady’s husband just returned from the chase (and so possibly Mrs. Fox Lane; see Rouquet, p. 37, Biog. Anecd., 1782, p. 223).

The walls are hung with paintings. Lot’s daughters, getting him drunk (in order to seduce him) and Correggio’s Jupiter embracing Io (which had unhappy consequences for Io) are above the Countess and Silvertongue; Correggio's Rape of Ganymede is above the head of the singing castrato. These paintings, with their references to sexual perversion, comment on the assembly; are more erotica of the sort hinted at in the second plate and verified by Le Sopha and Giulio Romano; and once again point to the subjects painted by "old masters." Out of place among all these ambiguous references is a large portrait of Counsellor Silvertongue.

Antal (p. 108) connects the composition with a number of elegant French salon-representations including Coypel's illustration for Molière’s Les Femmes Savantes (engraved by Joullain, 1726, and in England by Vandergucht) and J. F. de Troy's Reading from Molière (1740) (272-273).

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 4

Dobson, Austin. William Hogarth. (1907)

In the next picture (like the “Toilet Scene”) we pass to the bedroom of the countess, a lofty chamber, with the state bed standing, after the manner of the eighteenth century , in its alcove, and surmounted by a coronet. There is another over the mirror: by this time the old Earl is dead. The pictures on the wall are Jupiter and Io, Lot and his Daughter, the Rape of Ganymede, and the portrait of . . . Counsellor Silvertongue! That gentleman himself, “Gros et gras, le teint frais, et la bouche vermeille,” (like Molière’s “Tartuffe”), is lounging upon a sofa in the posture of a privileged visitor, and talking with easy familiarity to the countess who, in a peignoir and yellow dressing-gown, sits at her toilet-table under the hands of a Swiss valet, engaged in curling her hair. That she is now a mother is shown by the child’s coral hanging from her chair. She listens with a compliant expression to her admirer’s conversation, which, from this indication of the figures (a nun and a friar) on the screen at the back, and the fluttered masquerade-ticket in his hand, plainly relates to that entertainment; but we fail to read into her look “the heightened glow, the forward intelligence, and loosened soul of love,” which Hazlitt found in it. It is possible to be over-sympathetic as a critic.

These two are absorbed in their own affairs. The rest of the company, with the exception of one stout and slumbering gentleman in the background, are listening intently to the performances of an Italian singer and a German flute-player. Into the portrait of the former, alleged to be intended for famous contralto, Giovanni Carestini, Hogarth has infused all his spleen against exotic artists. The unwieldy, awkward form, the gross—almost swinish—physiognomy, the pampered look and posture, the profusion of jewels, and the splendid costume of the fashionable idol, are all expressed with the closest fidelity. The wooden-featured flute-player is a certain Weideman. The chief listener, a red-haired lady in a Pamela hat and white dress, represents Mrs. Fox Lane, afterwards Lady Bingley (It was Mrs. Fox Lane who, from a side box at the Opera, uttered the profane exclamation on the caricature in Plate II. of the Rake’s Progress. The enthusiasm for exotic minstrelsy sometimes took whimsical forms. In the Gentleman’s Magazine is recorded the case of another lady who justified a breach of promise in a Court of Equity upon the ground among other things that her lover was no admirer of Farinelli.). She rocks herself to the notes in an ecstasy, regardless of her black servant, who hands her some chocolate, and is amazed at his mistress’s enthusiasm. Sitting near her, a gentleman, with a fan dangling from his wrist, twists his face into an affected simper of delight; next to him, a slim fribble with his hair in curl papers, and queue loose like a woman’s tresses, sips at his cup with a fixed look of resigned connoisseurship. Both of these last are fantastic and ridiculous: what other men—according to Hogarth—would listen, or make believe to listen, to Italian song—that “Dagon of the Nobility and Gentry which had so long seduced them to Idolatry”? The foreground is littered with invitation and other cards, while in the right-hand corner is a pile of recent purchases from the sale—perhaps at Mr. Cock’s in the Piazza—of the “collection of the late Sir Timy Babyhouse.” Beside these kneels a second black boy, who significantly touches the horns of an Actæon (78-79).

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 4

Quennell, Peter. Hogarth’s Progress. (1955)

Hogarth contrasted scenes as carefully and deliberately as he contrasted characters; and the somber background of the doctor’s consulting room accentuates the gaiety of the Countess’s bedroom. A coronet surmounts her looking-glass; for the old Earl has at length expired, and she can now plunge more and more deeply into the absorbing pleasures of high life. Although she has recently given birth to a child, whose coral comforter hangs on the back of her chair, at the moment it is safe in the nursery and, while a Swiss barber prepares to dress her curls, she listens to the easy talk of dear seductive Silvertongue as, with Crebillon’s novel beside him, he reclines comfortably on the brocaded sofa. He is proposing that they should attend a masquerade . . . Again we return to questions of taste. The walls are decorated with large Italian canvases—among others a copy of Corregio’s Jupiter and Io; a basket, loaded with exotic objects of virtu, has just been carried in from the sale-room; and two foreign performers—a German flautist named Weidman and the well-known Italian singer, Giovanni Carestini—arouse the ecstatic admiration of the red-haired lady in the straw hat, who billows toward them, almost swooning with delight, like some huge dependent bell-flower.

To each his separate self-centered world. The porcine singer, every finger of his plump right hand exhibiting a jeweled ring, is so lost in the beauties of his own art that he pays little attention to the behaviour of his audience—even to his red-haired admirer, recognized at the time as the portrait of a Mrs. Fox Lane, afterwards Lady Bingley (Mrs. Fox Lane was the “lady of distinction” whose cry of “One God, one Farinelli!” had electrified the opera-house.) whose fat husband, clutching his whip, has long ago begun to drowse. Between the sleeping squire and the warbling singer, a lean dandy, his hair still in curl-papers, broods contentedly over a cup of chocolate. The barber, too, inhabits a world of his own, testing his curling-tongs with a scrap of paper, yet lending an inquisitive ear to the talk of Counsellor Silvertongue. Hogarth displays his usual regard for detail—the sly, shifty, preoccupied barber is a representative of humanity’s idiot fringe, which he had studied with close attention and always loved to represent: Mrs. Fox Lane has the dead-white complexion and nearly invisible eyebrows that often accompany flame-red hair. Yet, thanks to the rhythmic line that flows through the groups of figures, this profusion of detail does not in any way detract from the work’s underlying unity. The frieze of courtiers and sycophants, stretched out across the stage, forms a long continuous arabesque (174-175).

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 4

Paulson, Ronald. Hogarth: His Life, Art and Times. (1971)

In Plate 3 the triangle is realized in the feeble-looking child who is the count’s mistress, the count, and the bawd, and quack who cater to his sexual wants. This is paralleled in Plate 4 by the countess’ lover, lawyer Silvertongue, the countess herself, and the denizens of her world, hairdressers, fashionable ladies, eunuch singers, and the like. Then in Plate 5, where the count and countess are reunited, the countess is placed, as in Plate 1, on one side her the dying count and on the other the fleeing lawyer, his murderer.

The first shows the earl’s quarters with the old masters he collects, pictures of cruelty and compulsion from which his present act of compulsion naturally follows, his portrait of himself as Jupiter furens, and his coronet stamped on everything he owns. . . . Then follows the empiric’s room, with his mummies and nostrums; the countess’ boudoir with her pictures of the Loves of the Gods and the bric-a-brac she bought at an auction, including Romano’s erotic drawings and a statue of Actaeon in horns . . . Here art has become an integral part of Hogarth’s subject matter: it is here for itself, a comment on itself, and also on its owners and on the actions that go on before it. In no other series is the note so insistent . . . it dominates every room, every plate. The old masters have come to represent the evil that is the subject of their series: not aspiration, but the constriction of old, dead customs and ideals embodied in bad art. Both biblical and classical, this art holds up seduction, rape, compulsion, torture, and murder as the ideal, and the fathers act accordingly and force these stereotypes on their children.

The trends toward art as theme and reader as active participant are further underlined by the importance placed on viewing. . . . in 4, Silvertongue himself looks helpless down from his canvas on the way the events are developing.

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 4

Lichtenberg, G. Ch. Lichtenberg’s Commentaries on Hogarth’s Engravings. (1784-1796). Translated from the German by Innes and Gustav Herdan (1966)

It is well known that in some ladies' calendars the longest days in the year are just those which are followed by a night of dancing. Oh! those hours! So long, so long! It is as if a stroke had paralysed the hands of the clock and time itself. There is no dealing with the sun; night will not come! It is just such a day in this picture; indeed the hours are even longer here, for there is to be not only a ball, but—a Masked Ball! If therefore some remedy could not be devised, time would not move at all. Lady Squanderfield has accordingly summoned everything to her aid, so as to make time feel the spur and compel it, if not to a fast trot, at least to the regulation police walk which she herself adopts on days when the following night is to be for sleep. One therefore rose this morning numero rotundo at ten, breakfasted till about eleven, rushed afterwards in a light, fetching dress to a saleroom to 'fetch' the dandies (here, the rumour goes, time actually moved apace), wounded a few gentlemen, acquired a few modem antiques which are strewn here on the floor, and so returned home. This brought the hour hand quite considerably beyond its zenith through the descending numerals. But there are still three or four hours until dinner, and for a healthy idler those are the most stubborn and heavy-footed of the whole morning because, for someone with a good digestion, dinner is said to have just such a prolonging effect upon time as have ball nights upon the time of somebody who loves dancing. Lady Squanderfield has a remedy for this, too. And what is it? It forms the content of the fourth picture.

She is holding her levee here, and in a style wherein are tastefully combined the dignity of the Earl's wife and the familiarity and condescension of the commoner. She accepts confidential morning visits in her bedroom; like a lady she has her hair dressed, and like a duchess gives a concert, small to be sure if one only counts the number of performers, but were they to be weighed on the scales of art or those of the goldsmith, very great and very costly. For to remark in passing, the singer is the famous eunuch, Carestini, and the flautist the renowned Weidermann, a German and a genuine man. It is a Privatissimum. That is going to cost a pretty penny! I refer here to the housekeeping book and the pious expression of the righteous steward in the second Plate.

The lady herself sits by the unveiled mirror, under the hands of her hairdresser, robed in a powder-mantle for the chaste draping of—the chair-back. Of the inner strife which we noticed on her brow in the first picture there is no longer any trace. In addition, all the rust of the city seems to have been polished off, and all the awkwardness which stuck to her from boarding-school has been cultivated away. We notice rather, and not without pleasure, a certain ease in her person, evidently a consequence of pleasing visions from the past or of the future. Oh! if only domestic happiness, and especially the event of which we see a very telling symbol hanging from the chair-back, had a greater part in it! It is a silver rattle with a teething coral which is hanging there; the lady is a mother! But alas! alas! not a trace of motherly feelings; all capacity for that has long been—cultivated away! If we try to imagine the source of the contentedness in that little sugar-face, we could hardly avoid pulling a long face—like the steward. Of the duet which is proceeding over there from Weidermann's flute and Carestini's little golden mouth, she hears nothing, or almost nothing. She listens simply and solely to the enchanting solo of her beloved lawyer, Silvertongue, who there in her own bedroom is lolling on the sofa opposite her, with oriental, effeminate indolence, as if in a harem. In his right hand he holds a ticket for today's Masked Ball, which he offers or actually hands to the lady.

What Mr Silvertongue is discussing here is a proposal that they should meet that evening, if possible, at the masquerade. This is sufficiently apparent from the lawyer's pointing to the Spanish screen where a fancy dress ball is depicted; but it acquires certainty from the fifth picture where we shall find that they have in fact met at a Masked Ball. It looks as if he were pointing particularly at a nun who in the foreground there is confessing to a monk, and as if he were recommending that disguise to the lady for their common devotions that evening. They were to be monk and nun. This is a very natural conjecture which should not be entirely disregarded, but it does not seem to me justified. The main indication would have to be by mouth; with the hand it could only be imperfectly made, especially considering the direction in which the Countess is looking. The pointing gesture is rather vague. In the picture which follows we shall see some of the ball costumes. And there the lady's costume bears as little re- semblance to a nun's as she herself to a saint. Trivial though this pointing gesture may appear here, it will prove important enough for poor Silver-tongue; it implicates, in fact, nothing less than a nail for his—gallows.

By his feet lies a book with the title Sofa. I do not know of a single . interpreter who mentions this detail with one word, and yet we may readily suppose that such a subtle and cunning man as Hogarth would never have taken the trouble to draw even a plain book, let alone one with that title, without some meaning and purpose. Now, the meaning is not hard to find; it has even a double one. The book is in fact the infamous, hot-blooded product of the pen of the younger Crébillon, entitled Le Sopha; conte morale, and is just as suitable for a lady's library as gilded oak-apples or candied night-shade berries for a Christmas tree. The touch is thus highly characteristic and surpasses even the finest touches which our artist has brought into this picture for the same purpose. The Countess is an abandoned creature. This seems to be the chief meaning and one which the whole character of the Plate unmistakably confirms. But, apart from all this, there is a secondary, a more comic meaning, which lies some- what deeper, and which Hogarth, who must have known the book, un-doubtedly intends to indicate. It is as much justified by the character of our artist's genius, as the first meaning by the character of the whole picture. Crébillon's fairy story is based upon the following plot: Almazéï, a sort of courtier at the Court of the Shah Baham, who was once as a punishment transformed into a sofa, related afterwards what he saw and heard in this guise, and a sofa, as we know, may well see and hear a thing or two in this world. There were certain conditions for his transformation and restoration—he was free to choose any shape, any material, any colour, any border, any embroidery, that he fancied; he might serve whomsoever he pleased, but he must remain a sofa until he happened to be present at an event which, of course, in the higher regions of society may be as frequent as the great conjunction of all the planets in the region of the sky—namely, innocence to innocence mutually lost. It is upon this Almazéï that the lawyer here reclines, and upon which the Countess has this morning placed her Crébillon. Oh! shuffle away, poor Almazéï, on your four legs; in this house there is no redemption for you!

Behind the lady whose silken lap, as we forgot to mention, appears to serve here as an ornamental case for her watch, especially if viewed from the sofa, stands the hairdresser. He is evidently of that country from which the English, at least the higher strata, have long drawn their servants, in order to have their hair dressed and their stomachs spoilt--coiffeurs and cooks, that is. They provide decoration and indigestion— of the stomach, I must expressly state, for to summon them or their recipes, to induce an indigestion of the head, is a new custom. In fine, the creature is a Frenchman. Hogarth's engravings, as our readers will have discovered by now, have their own symbols for Frenchmen, just as the calendar for the quarters of the moon. For every landmark in their path, which they travel or dance or crawl over the British horizon, they have their special symbol. This fellow here is still one of the hollow, hungry ones; he is still developing. He is seen here occupied with a pyrometric experiment; he breathes upon the curling tongs and listens to the voice of the advocate and in addition gapes at the—chairback. To do only one thing at a time is impossible for such a fellow. Despite his expression —un mouton qui rêve—one can wager that he already knows more about the Masked Ball and its implications than all the rest of the company. Something might come of that observation, provided he makes use of it in the proper quarters. This leads in a most natural way to a little remark about barbers and hairdressers. It is incredible for what great purposes Nature employs these otherwise unimportant creatures. Just as some insects carry fertilizing pollen to flower cups, which without that service would have remained sterile, so these people carry little family anecdotes from ear to ear, to induce a love of humanity which without these intermediaries would never have arisen. Or perhaps more appropriate: just as certain birds carry undigested seed-grains to inaccessible heights for the promotion of physical vegetation, so do these people, for the pro- motion of a certain kind of moral purpose, carry many a little anecdote- grain from the lowest quarters of the town into its higher regions. There really is a resemblance, and the whole difference lies in the trivial dissimilarity between the organs with which each deposits the undigested matter with the authority.

On the extreme left, richly decked and adorned with British gold, British diamonds and British fat, negligently draping an arm over the neighbouring chair, sits the eunuch, Carestini, said to be one of the loveliest little pipes which the knife of song has ever cut out of Italian cane. But just look at him now! Merciful Heavens! What an abominable bag-pipe does the masterpiece of creation become when Art presumes to carve a flute out of him. The tallowy lower jaw has neither beard nor force. The stiff cravat with its glittering diamond cross, the holy cross of the most unholy, are only a miserable substitute for that defect. The little mouth obtains thereby a certain pappy, sloppy insignificance, and if it rouses any feeling whatsoever in a grown-up person, it can only be the desire to hit it. How the fat has driven all form and elasticity out of those thick knees, and the whole leg-piece! Looking at those weak, wobbling lumps of legs,' we might take them for the wind bag of a bagpipe, which has just devoted a good deal of its content to a trill of the first water. Oh! if congenital neutrality in sex, though still in possession of its weapons, is said, as I have heard, to plane away the most important characteristics of the human face and human behaviour, in the eyes of knowledgeable men and women, what in the world can a creature unarmed, or even deprived of its arms, produce but such an abomination of bag growling. An unlovely work of art, to be sure, but valuable all the same. The sleeves and hem of his garment are heavily encrusted with gold thread, while diamonds glitter on each finger joint, on knee- and shoe-buckles and on his ear. Merely to achieve a setting for his voice, he has done everything possible.

Behind him stands our countryman, Weidermann, the famous virtuoso on the German flute. If I am not much mistaken, there lurks in the comer of his right eye, as well as at the corner of his mouth, a sort of good-natured roguery which, taken together with his hawk nose, speaks in favour of his honesty. He seems to smile in the very act of playing. In a company where every face and every gesture is so rich in the ridiculous, it is difficult to say what he is smiling at, if we assume that he has in fact looked beyond the music. But Herr Weidermann's honour as a virtuoso compels us here to assume that he has never taken his eyes off it. In that case, however, nothing would remain to explain the smile except a private estimate of the costs of their respective instruments. 'How much money did I give for my flute, and what did the eunuch pay in cash value for his pipe?' There is no neutrality in Weidermann's expression.

Next to the fattened Italian capon sits the English domestic cock, desiccated in service; in their extremes of physique, one worth as little as the other. There have been many interpretations of that figure. Someone has even made a Prussian Ambassador Michel out of it. Of course, many a Michel in this world may have looked like that, and may look like it in the future, but, according to all the rules of interpretation, this is certainly our hero, the Earl Squanderfield. If Hogarth himself were to reject this interpretation, he would have only himself to blame for being misunderstood. Of course, his Lordship appears thinner here than before, and what is still queerer, thinner than later that evening. But what does it matter? The dandy may have risen this morning but he is certainly not yet roused. He is still only a caterpillar. His head is already in the chrysalis state— the rest will follow, and before the dinner bell sounds the butterfly will appear in all its glory. These are only trivialities; after all, hips are neither here nor there. Since clothes have come to make the man. Nature has lost much of its custom. It is certainly a little malicious of our artist to serve up this half-transparent kipper together with the fattened Italian carp, as if on one dish. For really the legs of his Lordship are by no means the straws which they seem to a superficial observer. One need only cover over the two bamboo posts of the Italian, whose propinquity is obviously harmful to his Lordship's, to see that the latter are still a pair of legs upon which a man of some standing, who neither stands nor walks very much, may still stand and walk quite passably. But what has Hogarth done? With unpardonable malice, he has intentionally covered over more than half of his Lordship's left leg with the left leg of the Italian. Is that right? Indeed, if to cover over shortcomings in this way is not worse than to discover them, then I do not know the meaning of cover and discover. By this method, of course, one could in a moment turn the stoutest walking-stick of the most up-to-date Parisian dandy, or even of Hercules himself, into a mere matchstick. Thus the whole argument against identifying the former and future Squanderfield with this creature here, which is based upon the feeble legs of the subject, itself stands upon very weak legs. Besides, for an artist of Hogarth's vitality and wit, it would be harder than for others not to exaggerate the contrast once he had hit upon the idea. Oh! the best-trained wit, ridden by Reason itself, may run away with its rider once such artistic jumps are made. Then one usually tells only half the truth, or else six quarters of it, which, mutatis mutandis, comes to very much the same thing. But now let us listen to the other side of the argument: it must be Earl Squanderfield, for, in the first place, he sits there en papillotes, just as his love, or rather his semi-wife, sits over there, not with her husband but merely with her lover. He is waiting for the curling tongs of the Frenchman whom they both employ. Nobody but a husband has the right to have himself nipped in that way at a lady's levee. Thus they belong together serviliter at least; they are married à la mode. Secondly, just look at the head: is not that a horned animal tout enticer? And who in the wide world could fail to see it? Even the little black boy there in the right-hand corner notices it and points with his finger at the papillotes of a miniature Acteon which has just arrived from the auction. Yes, indeed brother Acteon with his ten-branched antlers even seems to point with his stump of an arm at the member of his Order, Squanderfield, who has seven branches: ‘Just look, isn't that one of ours too?' And the poor devil of a Lord really seems to have just recognized his little brother. Oh he already feels a pinch in some part of his being! For who would sip chocolate even the hottest, like that, if he were not burning somewhere else as well? At present, his eye probably sees as little as his ear hears or his tongue tastes; it is spiritual food which he consumes or tries to digest perhaps a few paper sandwiches from his steward, and something of the amorous collation to which Almazéï is listening over there. He surely is the husband— à la mode..

Thirdly, what speaks very strongly in favour of this interpretation is the expression, and even the attire, especially if one compares it with the Squanderfield of the second Plate. He loves fancy coats. Even at the scene of the catastrophe in the fifth Plate, he wears one of these, whose cut is however different from that in the second Plate. But, one might object, the bon-ton plaster behind the ear is missing. Answer: that is what happens to plasters in the night, and behind the ear there really is something discernible which might well have deserved a one inch bon-ton plaster It is also the first time that our hero has favoured us with his right ear- it was always the left that we saw. That an evil which is usually symmetrical should have thus broken the rule for once would, in this household at least (with the exception perhaps of the mantelpiece ornaments in the second Plate), be precisely in order. A stronger objection is one which I have raised myself: this gentleman has, if else I see aright, a hat with a cockade under his arm, which, according to English custom, would be an officer's hat. His Lordship is not an officer, to be sure, but how if last night his Lordship has perhaps acted the officer, and has only just returned home, as the other day, or that in the confusion he has made an acquisition just as he did before? My readers may take their choice here, if they find it worth their while. Perhaps their choice will be made easier by the consideration that our hero might also have been brought into such close contact with the Italian to demonstrate that if in this world a man wished to acquire a sort of eunuch-credit for all kinds of courage and bravery, he need not always use precisely the knife.

The lady in the bonnet, already somewhat beyond the equinox of life, in the direction of winter, is a certain Mrs Lane, and the slumbering fox-hunter in the background, with the black wig and the black cravat, is Mr Lane, her husband. He was such a passionate adherent of that kind of hunting that he was nicknamed 'Fox-Lane'. After his decease, the simple Mrs Lane became the complex Lady Bingley. Thus, my dearest lady readers, you who are beyond the equinox of life in the direction of winter, and still walk without a companion, for God's sake, don't despair too soon! In our clime, at least, the sun of your luck behaves sometimes, even if not always, like the Queen of Days which bears its name (Sunday). It presents the Spring of life, and even its Summer, with tit-bits rather than solid, lasting nourishment. Only in Autumn ripens the drink of the gods which delights the heart of man. This is the season of the kingly Bergamote, the refreshing St Germain, of the greasy Poire de Beurrée blanche, and our pickled cabbage, and all that keeps until the depths of winter.

Madame's glance is directed not only at the warbling half-man in the physiological sense, but also at the half-man in the military sense, probably more to evade the melodious stream issuing from that contemptible orifice than perhaps to seek the source itself. She is delighted; she is enraptured. The way she throws out her arms conveys to the eye what the ear necessarily misses—the cadenza to which Carestini's song is approaching, if he has not reached it already; just as the attitude of the whole Madame in corpore illustrates its ravishing beauty. If the cadenza does not come to an end soon, then indeed the cadence of the scale may become for Madame a cadence from the chair. How very differently her husband behaves behind there, if sleeping can be called behaving. Not a trace of resemblance, apart from the trivial circumstance that he, too, is as if carried away, and is not quite secure against a cadence from the chair. But was it perhaps our artist's intention to insinuate something here to our eye which escapes our ear—that this concert is in fact a trio in which Mr Lane plays the third instrument, I mean an accompaniment on nasal reedstops? He seems at least to have the instrument tuned and set in position, and to judge from his strong and healthy chest, the requisite bellows will be in pretty good condition. How peacefully he sleeps! But oh! how he would start up if the Tally-ho! suddenly sounded, or if some English bass eunuch tuned up his 'the echoing hom calls the sportsmen abroad', etc., or even if instead of Carestini and Weidermann, Malampus gave tongue accompanied by Lalaps, Okydromus, Pamphagus and Hylaktor. Then, maybe, Madame would go to sleep. Is this, too, a marriage à la mode..

Immediately beside the unfeeling fox-hunter we notice, alas! as the eternal contrast to all wild hunting and shooting, the most sugary sentimentality of behaviour, and the extreme expression in masculine shape of affected delight. What a little balsam box it is compared with the tarpot behind there! What a pity that the little plaster on the lower lip, greatly though it heightens the charm of that dainty face, somewhat disturbs the effect of the appreciative smirk. Without it we might have learnt much better from his very lips what is, of course, demonstrated more or less by the fop's whole behaviour; that is, how to give expression to the ineffable. In order to indulge his ear in the highest degree, he denies his palate the chocolate and, probably, since he turns his back so care- fully on the man with the riding crop, deprives his nose also of part of the stable perfume which may emanate thence. Although the loud exclamation of wonder is necessarily missing, the five exclamation marks which he embodies with the fingers of his left hand unmistakably denote its silent presence. From the same hand, opened like a fan, hangs the folded fan of the lady herself. He has apparently taken it into custody in order to have it redeemed in the end by a kiss. That is how everything hangs together m this little man. Just add the age in the sixties, a parrot-green coat with rose-coloured lining, and a pair of shoes with red heels, and the future natural historian of the affections in the male of the species will have just about the complete characteristics of an old coxcomb.

Behind the enraptured lady (I mean the one sentimentally enraptured of Carestini, and not the more realistic adorer of Silvertongue) we see a head, or rather a head stares out at us, which, of course, is not exactly the most beautiful, but certainly one of the most characteristic in the whole gathering. It is the head of the negro who is serving the chocolate into the blue. Truly with the three diamonds in his face, of which the one upon his nose is not genuine, but merely borrowed from the window, he puts in the shade, completely and absolutely, all the diamonds worn by the eunuch in ear and solitaire. Isn't that expressive language? And wasn't it clever to give more prominence to the symbol of the new moon which the African there carries on his shoulders than to the Italian full moon? If one tried to draw a little night piece like that one would soon find out. There is no affectation in it; it is pure, solid, human-animal instinct which draws the axis of his eyes so firmly towards the Italian. Probably it is not so much the voice of the singer which fascinates him, but the gestures which accompany it and the orifice from which it oozes out. He laughs about the little pap-and-rag mouth which once washed itself in the soft and feminine Tiber, and himself reveals a mouth that has been rinsed in the Niger or the Senegal, and one of such dimensions that neither the Senegal nor the Niger nor any other famous river god would need to fear complaints about shortage, if he were to let his store, which had poured hitherto from his urn, spout in future from such a head.

We have already heard that the Countess was at an auction this morning. Here we see from the auction catalogue which lies on the floor to the right that some collection was put up for sale and the name of the owner; it follows from the kind of articles bought there, and which we see standing around here, that it was a collection of objets d'art. The English title of the inventory is: 'A catalogue of the entire collection of the late Sir Timothy Babyhouse, to be sold by auction.'

All the junk which her Ladyship bought there belongs, we observe, to the class of antiques which we saw on the mantelpiece in the second Plate. The articles are so arranged that the whole resembles a procession in which the members become more important the farther back they are. It is reminiscent of a triumphal procession. In front there trots on its four feet an unknown little animal which seems to have precedence only because of its unimportance; behind it crawl a couple without feet, next to it a little bowl, then an atrocious cat's head, a few enchanted princesses together with the magician, then a horrible pottery monster in the form of a candle-holder; now, more important, a butter dish, and still more important, a mystic pot with a mystic seven upon it, and, finally, most important of all, the Imperator Acteon himself with the crown of victory upon his head. He leans against a wash-basin of majolica ware hand-painted by Giulio Romano, a great rarity. Raphael-like rubbish of this sort is to be found everywhere; the picture itself represents a nude woman being bitten by a wicked goose. The rear is brought up by a magnificent vase of the pot-pourri type.

Still more mystical perhaps than the seven on the little pot may be the round figure of 100 upon Acteon's belly, but this we shall leave an open question. In the counting-house of her Ladyship's father, such round numbers could have been seen on more important slips of paper. One of the figures is marked with the number four. Her Ladyship has thus attended the auction from the beginning, and held out till Lot 100—a very long time if it all took place the same morning. But there was a little statue to be bought for her lord and master, to hang his hat on in the evening. Thus the series of little nonsensical objects there on the floor becomes in the end very significant for our story. It is irrefutable evidence of crude lack of taste, coarse sensuality, and what is ultimately not much better (videatur the steward) of thriftlessness in buying, for want of a better occupation. What may she have paid for that doll with the horns? To form an opinion we should have to imagine another such creature being present at the same auction, or several more of them, each just as extravagant, wise, and well brought up as Madame. We must imagine, too, the noble contempt of money and the elevated feelings which so easily overpower ladies' souls in that sort of sales excitement, especially if their absent husbands are perhaps engaged with equal ardour in some similar glory-, rank-, or title-auction. Then one should only hear how those ladies, as if in vocal contest, now with alternating voices, now with simultaneous duet and trio, drive one another higher and higher and, like jealous nightingales, continue to warble till first one, then the other, worn out at last, falls down from the branch. Then what? Oh, the doll was not worth three farthings, but the joke of buying a man with horns in the presence of so many gentlemen and ladies, and the pleasure of seeing the nightingales fall, one after another. . . For a satisfaction like that, as many golden sovereigns would be but a trifle.

Our artist has perhaps exaggerated a little here. Who in the world, many a lady might ask, would buy such jokes, and moreover such moral filth? Fi donc! Quite right. But how if we were to translate the numbers here into book titles, and in this way transform the whole collection into a modem lady's library? How's that to de done? Even supposing the little dishes and bowls might signify a cookery book or a recipe for making candles or boiling soap, this does not imply that they must have that meaning. Could they not just as well be instructions for face-tanning, for the improvement of the hair roots, and for painting a pink and white com- plexion? And if even the enchanted princesses, the dwarf, the gander on the dish, and, finally, the homed creature with the one and two noughts on his belly, were transformed into books, would the library look a jot more respectable than the floor does here? Hardly, hardly. . . .

The little procession becomes almost comic if we consider that it is making straight for Carestini, and if we then recall Orpheus—and why not recall him here? If Orpheus with his harp made oak trees and granite boulders approach him in a waltz, why should not Carestini with his pipe entice that Nurnberg ware? Either the one is not a true story, or the other is at least possible. To return to the idea of translation into book titles, the small, dainty animal which is trotting on its little feet at the head of the procession, just because it trots on little feet and is so dainty, would have to be a poetry almanack and, by the same token, its two legless, prosaic companions could be nothing else but a couple of prose almanacks (Taschenkalenders).

Close to Carestini's chair lie visiting and invitation cards, trump upon trump. Some turn upwards their acquired inscribed aspect, others their congenital printed one; still others show nothing, just as they happen to have fallen. We shall briefly review them.

Lady Squander (so she is called on all these cards, instead of Squanderfield, perhaps because most of the fields are already squandered) is invited : (1) to Lady Townley's Drum (this is a sort of party where they gamble and talk nineteen to the dozen), and that is for next Monday. On the card stands Munday instead of Monday, a telling indication of her Ladyship's learning. (2) To Lady Heathen's Drum-major, where everything is more spacious and magnificent, gambling as well as tongue-wagging, and that is for Sunday next. Pious John Bull does not forgive a soul for playing and making music on Sundays, that is why the Sabbath breaker is called here Lady Heathen. But so far as I know, the Jew's harp of tongue-wagging, which is played at all parties, is as little forbidden on Sundays in England as it is with us. (3) To Miss Hairbrain's Rout (also a sort of party which, if it is what its name says, must be like a small riot). Finally, there lies with them No. (4), the card upon which a foreign Count Basset inquires after the health of her Ladyship. He has apparently gone to England to learn English, and here gives a proof of his proficiency, for which reason we quote it in full: 'Count Basset begs to no how Lade Squander sleapt last nite.'

By the pictures on the walls, our artist continues to throw more and more into relief his conception of the ladies' master-passion. He started with the Primer for Young Women over there on the sofa; below in the basket he continued his tale, and on the walls we now see the sequel. There are four pictures. We must be brief. On the right hangs the 'Consequences of Intoxication', a few rungs above the middle stage, in the story of Noah and his daughters. The explanation of the dish picture was taken from a daily paper which like a falling leaf (fliegendes Blatt) has long since flown away. The explanation of the present picture (the biblical), however, we should have to copy from leaves which are anything but flying, and which it is hoped may therefore never fly away this side of the Rhine, wherefore we refer the reader to them. Next to this picture hangs the 'Consequences of Masquerades', in the story of the beautiful princess lo, where she, too, is bitten by the enraged Jupiter clad in his usual Thundercloud-domino. This is a copy of a very well-known presentation of that biting by Michelangelo Buonarroti, bought of course by her Ladyship for the original itself, and perhaps even paid for I as such.

To the left hangs Jupiter for the third time, again en masque, for we must confess that the gander on the dish over there was this same Jupiter. Pictures like that might induce anybody to try his luck for once at a Masked Ball, especially if he is a friend of Lady Heathen's. Jupiter appears this time in the guise of an eagle carrying his Ganymede to Olympus. What is queer is that the King of the Gods is about to bite again here. It almost makes us afraid to look. Oh, if only Ganymede would do the riding this time; I mean if only he would be, as the French so excellently put it, un cheval sur un aigle! As he is now hanging from the eagle, this will not come to a good end. I tremble, I tremble! Jupiter who hovers there just above Carestini's head is listening to the divine voice of that mortal; 'I must have such a singer, too,' he thinks, and no sooner thought than done, proceeds immediately with his own noble beak to the operation.

Above that picture, in Olympus itself and among the Immortals, there hangs, somewhat ominously, a portrait of Mr Silvertongue, quite undisguised, in all the exterior dignity appropriate to a Head of the House. At his feet there the horned animal felled by him gnaws at its chain. Good! We shall leave it at that. In the next two Plates we shall see both the hanging and the felling in more solid form.

Silvertongue's picture was hung just opposite the sofa for the sole purpose of promoting devotion. As soon as that ceases, he receives, as we shall hear, a different place, or rather, as soon as that idol obtains another place, the devotion ceases.

A trifle to finish with, for surely every puzzle is a trifle. On the canopy of the lady's bed the artist has put a French lily. Now how in the world do the French arms come to be on an English bed? (114-128)

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 4: Cards

Invitations and cards are scattered on the floor.

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 4: Cards

Shesgreen

Lying on the floor across from the youth are playing cards and correspondence, both indicative of the Countess’s social life. “Ly Squanders Com is desir’d at Lady Townlys Drum Munday Next”; “Lady Squanders Company is desir’d at Miss Hairbrains Rout”; “Lady Squanders Com is desir’d at Lady Heathans Drum Major on next Sunday”; “Count Basset begs to no how Lade Squander Sleapt last nite.” The spelling in these notes is a judgment upon their authors’ literacy (54).

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 4: Cards

Paulson, Hogarth's Graphic Works

Various cards lie at the singer's feet: a five and six of diamonds and notes inscribed “Ly Squanders Com is desir'd at Lady Townly Drum Munday next,” “Lady Squanders Company is desi’d at Miss Hairbrains Rout,” “Lady Squanders Com is desir’d at Lady Heathans Drum Major on next Sunday,” and “Count Basset begs to no how Lade Sleapt last night." (A rout, drum, or drum major was a noisy assembly of fashionable people at a private house. Count Basset may be a memory of the character in the Vanbrugh-Cibber comedy, The Provok’d Husband [1727/8]; cf. also "the borough of Guzzledown" and the second Election print, Plate 218.) (273).

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 4: Cards

Lichtenberg

Close to Carestini's chair lie visiting and invitation cards, trump upon trump. Some turn upwards their acquired inscribed aspect, others their congenital printed one; still others show nothing, just as they happen to have fallen. We shall briefly review them.

Lady Squander (so she is called on all these cards, instead of Squanderfield, perhaps because most of the fields are already squandered) is invited : (1) to Lady Townley's Drum (this is a sort of party where they gamble and talk nineteen to the dozen), and that is for next Monday. On the card stands Munday instead of Monday, a telling indication of her Ladyship's learning. (2) To Lady Heathen's Drum-major, where everything is more spacious and magnificent, gambling as well as tongue-wagging, and that is for Sunday next. Pious John Bull does not forgive a soul for playing and making music on Sundays, that is why the Sabbath breaker is called here Lady Heathen. But so far as I know, the Jew's harp of tongue-wagging, which is played at all parties, is as little forbidden on Sundays in England as it is with us. (3) To Miss Hairbrain's Rout (also a sort of party which, if it is what its name says, must be like a small riot). Finally, there lies with them No. (4), the card upon which a foreign Count Basset inquires after the health of her Ladyship. He has apparently gone to England to learn English, and here gives a proof of his proficiency, for which reason we quote it in full: 'Count Basset begs to no how Lade Squander sleapt last nite' (126-127).

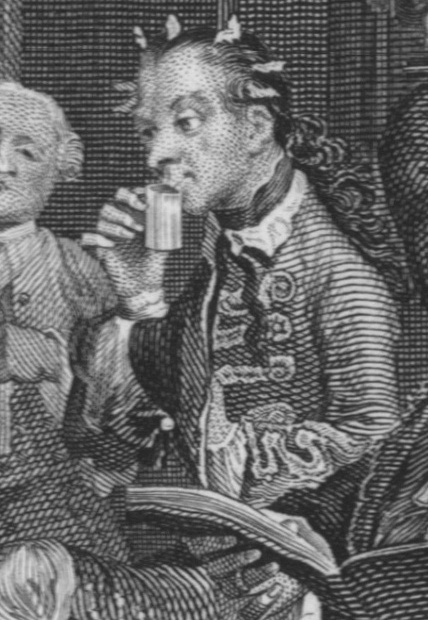

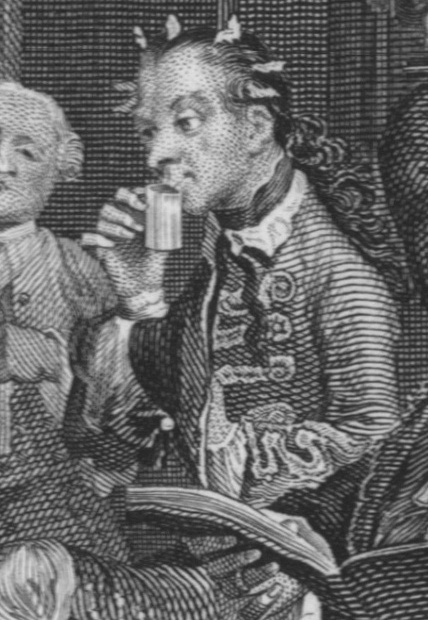

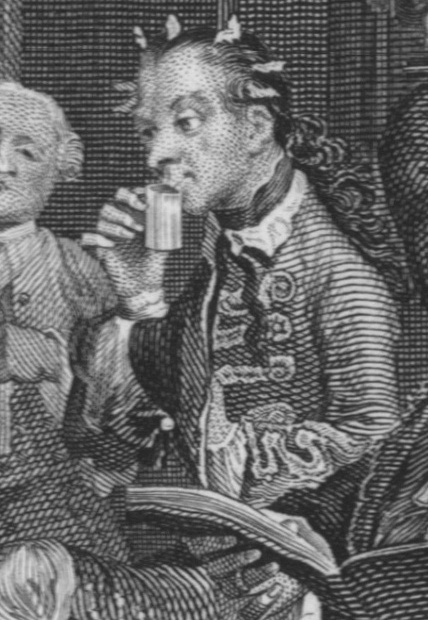

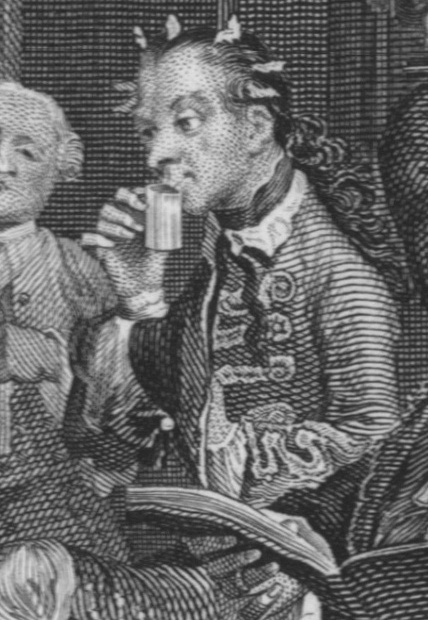

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 4: Castrato

A pompous castrato sings; his presence foreshadows the emasculation of the husband in the next scene.

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 4: Castrato

Shesgreen

Most of the group sit around in strained, affected poses. The center of focus is a bloated castrato (probably Francesco Bernardi, an Italian singer who lived in England for a while). Overdressed in gold lace and tastelessly bedecked with jewels, the vain fellow sits haughtily back in his chair, unaware that only two in the whole group listen to him (54).

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 4: Castrato

Paulson, Hogarth's Graphic Works

The singer is probably the castrato mezzo-soprano Francesco Bernardi, called Senesino (1690?-1750?), who had sung with Handel until 1733 and then sang with the rival company at the King’s Theatre, Haymarket. The face, with its turned up nose bear a close resemblance to contemporary portraits of Senesino (by Goupy, engraved by Kirkall; by Hudson, engraved by Van Haecken, 1735; cf. Berenstadt, Cuzzoni, and Sensino, Plate 310). By 1735 Senesino had returned to his native Siena. Nichols, therefore, believed the singer was meant to be Giovanni Carestini (1705-c. 1758), the "finest and deepest counter-tenor that has perhaps ever been heard" (C. Burney, A General History of Music, 1789, 4, 369) brought to England by Handel in 1733 to replace Senesino (273).

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 4: Castrato

Dobson

Into the portrait of the[castrato], alleged to be intended for famous contralto, Giovanni Carestini, Hogarth has infused all his spleen against exotic artists. The unwieldy, awkward form, the gross—almost swinish—physiognomy, the pampered look and posture, the profusion of jewels, and the splendid costume of the fashionable idol, are all expressed with the closest fidelity (79).

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 4: Castrato

Lichtenberg

On the extreme left, richly decked and adorned with British gold, British diamonds and British fat, negligently draping an arm over the neighbouring chair, sits the eunuch, Carestini, said to be one of the loveliest little pipes which the knife of song has ever cut out of Italian cane. But just look at him now! Merciful Heavens! What an abominable bag-pipe does the masterpiece of creation become when Art presumes to carve a flute out of him. The tallowy lower jaw has neither beard nor force. The stiff cravat with its glittering diamond cross, the holy cross of the most unholy, are only a miserable substitute for that defect. The little mouth obtains thereby a certain pappy, sloppy insignificance, and if it rouses any feeling whatsoever in a grown-up person, it can only be the desire to hit it. How the fat has driven all form and elasticity out of those thick knees, and the whole leg-piece! Looking at those weak, wobbling lumps of legs,' we might take them for the wind bag of a bagpipe, which has just devoted a good deal of its content to a trill of the first water. Oh! if congenital neutrality in sex, though still in possession of its weapons, is said, as I have heard, to plane away the most important characteristics of the human face and human behaviour, in the eyes of knowledgeable men and women, what in the world can a creature unarmed, or even deprived of its arms, produce but such an abomination of bag growling. An unlovely work of art, to be sure, but valuable all the same. The sleeves and hem of his garment are heavily encrusted with gold thread, while diamonds glitter on each finger joint, on knee- and shoe-buckles and on his ear. Merely to achieve a setting for his voice, he has done everything possible (118-119).

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 4: Cuckold

Shesgreen

Before them a black boy plays with a group of tasteless art objects purchased by the lady at an auction. A book beside them reads “A Catalogue of the Entire Collection of the Late Sr. Timy. Babyhouse to be Sold by Auction.” The lot includes a tray inscribed with an erotic version of Leda and the swan by “Julio Romano” and a statuette of Actaeon; the boy points to Actaeon’s horns to interpret the import of the conversation behind him (54).

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 4: Cuckold

Uglow

The music and the fallen cards on one side of the room are balanced on the other by the little slave in Moorish dress, who grins and points at the antler horns of Actaeon, changed into a stag for watching Diana bathe naked (381).

The clutter of objects from the auction, still with their tickets on, leads our eye to the figurine of Actaeon, while a strong diagonal runs across the page-boy’s grin implicating the cuckolding couple and his pointed finger suggesting that the fop is as ridiculous, and “unnatural”, as the statue (385).

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 4: Cuckold

Dobson

In the right-hand corner is a pile of recent purchases from the sale—perhaps at Mr. Cock’s in the Piazza—of the “collection of the late Sir Timy Babyhouse.” Beside these kneels a second black boy, who significantly touches the horns of an Actæon (79).

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 4: Cuckold

Lichtenberg

All the junk which her Ladyship bought there belongs, we observe, to the class of antiques which we saw on the mantelpiece in the second Plate. The articles are so arranged that the whole resembles a procession in which the members become more important the farther back they are. It is reminiscent of a triumphal procession. In front there trots on its four feet an unknown little animal which seems to have precedence only because of its unimportance; behind it crawl a couple without feet, next to it a little bowl, then an atrocious cat's head, a few enchanted princesses together with the magician, then a horrible pottery monster in the form of a candle-holder; now, more important, a butter dish, and still more important, a mystic pot with a mystic seven upon it, and, finally, most important of all, the Imperator Acteon himself with the crown of victory upon his head. He leans against a wash-basin of majolica ware hand-painted by Giulio Romano, a great rarity. Raphael-like rubbish of this sort is to be found everywhere; the picture itself represents a nude woman being bitten by a wicked goose. The rear is brought up by a magnificent vase of the pot-pourri type.

Still more mystical perhaps than the seven on the little pot may be the round figure of 100 upon Acteon's belly, but this we shall leave an open question. In the counting-house of her Ladyship's father, such round numbers could have been seen on more important slips of paper. One of the figures is marked with the number four. Her Ladyship has thus attended the auction from the beginning, and held out till Lot 100—a very long time if it all took place the same morning. But there was a little statue to be bought for her lord and master, to hang his hat on in the evening. Thus the series of little nonsensical objects there on the floor becomes in the end very significant for our story. It is irrefutable evidence of crude lack of taste, coarse sensuality, and what is ultimately not much better (videatur the steward) of thriftlessness in buying, for want of a better occupation. What may she have paid for that doll with the horns? To form an opinion we should have to imagine another such creature being present at the same auction, or several more of them, each just as extravagant, wise, and well brought up as Madame. We must imagine, too, the noble contempt of money and the elevated feelings which so easily overpower ladies' souls in that sort of sales excitement, especially if their absent husbands are perhaps engaged with equal ardour in some similar glory-, rank-, or title-auction. Then one should only hear how those ladies, as if in vocal contest, now with alternating voices, now with simultaneous duet and trio, drive one another higher and higher and, like jealous nightingales, continue to warble till first one, then the other, worn out at last, falls down from the branch. Then what? Oh, the doll was not worth three farthings, but the joke of buying a man with horns in the presence of so many gentlemen and ladies, and the pleasure of seeing the nightingales fall, one after another. . . For a satisfaction like that, as many golden sovereigns would be but a trifle.

Our artist has perhaps exaggerated a little here. Who in the world, many a lady might ask, would buy such jokes, and moreover such moral filth? Fi donc! Quite right. But how if we were to translate the numbers here into book titles, and in this way transform the whole collection into a modem lady's library? How's that to de done? Even supposing the little dishes and bowls might signify a cookery book or a recipe for making candles or boiling soap, this does not imply that they must have that meaning. Could they not just as well be instructions for face-tanning, for the improvement of the hair roots, and for painting a pink and white com- plexion? And if even the enchanted princesses, the dwarf, the gander on the dish, and, finally, the homed creature with the one and two noughts on his belly, were transformed into books, would the library look a jot more respectable than the floor does here? Hardly, hardly. . . .

The little procession becomes almost comic if we consider that it is making straight for Carestini, and if we then recall Orpheus—and why not recall him here? If Orpheus with his harp made oak trees and granite boulders approach him in a waltz, why should not Carestini with his pipe entice that Nurnberg ware? Either the one is not a true story, or the other is at least possible. To return to the idea of translation into book titles, the small, dainty animal which is trotting on its little feet at the head of the procession, just because it trots on little feet and is so dainty, would have to be a poetry almanack and, by the same token, its two legless, prosaic companions could be nothing else but a couple of prose almanacks (Taschenkalenders) (124-126).

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 4: Flute Player

An effete flute player plays his instrument. The effeminate male figures in the plate demonstrate a concern that feminizing influences are dominating the attention of English society. They also foreshadow the metaphorical emasculization of Squanderfield in the next plate.

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 4: Flute Player

Paulson, Hogarth's Graphic Works

The thin man next to the singer has been identified as Herr Michel Prussian envoy, and the flutist as Weidemann, a German musician. The country-type sleeping with a riding whip in his hand, may be the voluble lady’s husband just returned from the chase (and so possibly Mrs. Fox Lane; see Rouquet, p. 37, Biog. Anecd., 1782, p. 223) (273).

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 4: Flute Player

Dobson

The wooden-featured flute-player is a certain Weideman (79).

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 4: Flute Player

Lichtenberg

Behind him stands our countryman, Weidermann, the famous virtuoso on the German flute. If I am not much mistaken, there lurks in the comer of his right eye, as well as at the corner of his mouth, a sort of good-natured roguery which, taken together with his hawk nose, speaks in favour of his honesty. He seems to smile in the very act of playing. In a company where every face and every gesture is so rich in the ridiculous, it is difficult to say what he is smiling at, if we assume that he has in fact looked beyond the music. But Herr Weidermann's honour as a virtuoso compels us here to assume that he has never taken his eyes off it. In that case, however, nothing would remain to explain the smile except a private estimate of the costs of their respective instruments. 'How much money did I give for my flute, and what did the eunuch pay in cash value for his pipe?' There is no neutrality in Weidermann's expression (119).

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 4: Hairdresser

The lady is styled by a hairdresser who holds curling papers for her hair. The effeminate male figures in the plate demonstrate a concern that feminizing influences are dominating the attention of English society. They also foreshadow the metaphorical emasculization of Squanderfield in the next plate.

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 4: Hairdresser

Quennell

The barber, too, inhabits a world of his own, testing his curling-tongs with a scrap of paper, yet lending an inquisitive ear to the talk of Counsellor Silvertongue. Hogarth displays his usual regard for detail—the sly, shifty, preoccupied barber is a representative of humanity’s idiot fringe, which he had studied with close attention and always loved to represent (175).

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 4: Hairdresser

Lichtenberg

Behind the lady whose silken lap, as we forgot to mention, appears to serve here as an ornamental case for her watch, especially if viewed from the sofa, stands the hairdresser. He is evidently of that country from which the English, at least the higher strata, have long drawn their servants, in order to have their hair dressed and their stomachs spoilt--coiffeurs and cooks, that is. They provide decoration and indigestion— of the stomach, I must expressly state, for to summon them or their recipes, to induce an indigestion of the head, is a new custom. In fine, the creature is a Frenchman. Hogarth's engravings, as our readers will have discovered by now, have their own symbols for Frenchmen, just as the calendar for the quarters of the moon. For every landmark in their path, which they travel or dance or crawl over the British horizon, they have their special symbol. This fellow here is still one of the hollow, hungry ones; he is still developing. He is seen here occupied with a pyrometric experiment; he breathes upon the curling tongs and listens to the voice of the advocate and in addition gapes at the—chairback. To do only one thing at a time is impossible for such a fellow. Despite his expression —un mouton qui rêve—one can wager that he already knows more about the Masked Ball and its implications than all the rest of the company. Something might come of that observation, provided he makes use of it in the proper quarters. This leads in a most natural way to a little remark about barbers and hairdressers. It is incredible for what great purposes Nature employs these otherwise unimportant creatures. Just as some insects carry fertilizing pollen to flower cups, which without that service would have remained sterile, so these people carry little family anecdotes from ear to ear, to induce a love of humanity which without these intermediaries would never have arisen. Or perhaps more appropriate: just as certain birds carry undigested seed-grains to inaccessible heights for the promotion of physical vegetation, so do these people, for the pro- motion of a certain kind of moral purpose, carry many a little anecdote- grain from the lowest quarters of the town into its higher regions. There really is a resemblance, and the whole difference lies in the trivial dissimilarity between the organs with which each deposits the undigested matter with the authority (117-118).

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 4: Bride

In this scene, the new countess, also being styled is “educated” by Silvertongue, the lawyer who will soon be (if he is not already) her lover. Silvertongue instructs the girl, not in Latin or rhetoric, but in the use of her body. He invites her to a masquerade. Her style and demeanor have drastically changed since the first plate.

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 4: Bride

Shesgreen

Having cast off her middle-class awkwardness and inhibition, the Countess imitates the life style of the aristocracy (the coronets about the room indicate that the old Earl is dead). In contrast to her husband’s bizarre passion for young girls, the Countess’s middle-class origins reveal themselves in her interest in an ordinary live affair. Wearing jewelry on her hair and fingers and dressed in a low-cut gown, she sits at her levee with her back to her guests, oblivious to the music, attentive only to the addresses of Silvertongue. A child’s rattle on her chair reveals that she has a baby which she has the servants care for (54).

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 4: Bride

Uglow

The magic that his wife succumbs to is more frivolous. Hogarth paints her in her bedchamber receiving guests at her toilette---a much derided habit imported from France. The coronets over her pink-canopied bed (its open curtains a salacious female invitation), and over her gilt mirror, declare that her husband is now an Earl; the little coral rattle hanging from her chair tells us that she has a child, making the disease of the previous scene more ominous still. Neither change in status, to mother or to Countess, has had a sobering effect. She tosses a cloth across her shoulders to protect her yellow satin while the French valet curls her hair (379-380).

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 4: Bride

Paulson, Hogarth's Graphic Works

The baby's rattle on the back of her chair suggests that she is now a mother and so neglecting her child J. Ireland, I , 25 n., 38. believes her shape showed her to be pregnant) (273).

The Countess is engaged in pleasant conversation with Counsellor Silvertongue while a barber dresses her hair for the day (273).

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 4: Bride

Dobson

the countess . . . in a peignoir and yellow dressing-gown, sits at her toilet-table under the hands of a Swiss valet, engaged in curling her hair. That she is now a mother is shown by the child’s coral hanging from her chair. She listens with a compliant expression to her admirer’s conversation (78).

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 4: Bride

Quennell

Although she has recently given birth to a child, whose coral comforter hangs on the back of her chair, at the moment it is safe in the nursery and, while a Swiss barber prepares to dress her curls, she listens to the easy talk of dear seductive Silvertongue as, with Crebillon’s novel beside him, he reclines comfortably on the brocaded sofa (174).

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 4: Bride

Lichtenberg