Marriage a la Mode: Plate 6

1745

13 3/4” X 17 7/16” (H X W)

Engraved and etched from Hogarth's painting.

View the full resolution plate here.

View the painting here.

Here we see the results of the dalliances of the Squanderfields as detailed in Plates 3 and 4. Hogarth's final plate in the series, showing the countess's child caressing her dead mother's face, is one of the truly touching scenes in his work. Her lover and her husband dead, the countess has poisoned herself. The Count has also squandered his fortune, most notably in the promise of a strong family line. In this plate, the couple’s child, female, but more importantly, congenitally syphilitic, becomes an important emblem of waste and despair. This daughter wears a leg brace and a patch—both signs of her only inheritance. Quennell calls the child "Dead Sea fruit;" (177) her syphilis, not to mention her sex, determine the end of the Squanderfield line. Jarrett states that there is "a certain divine justice in it all, that although God might visit the sins of the fathers upon the children at least there are sins to be visited" (England 206). The child also redeems the wife somewhat, as she is certainly the daughter of the Lord, resembling him in the legs and in the congenital disease. Paulson notes:

The Countess’s child is significant both because she is a girl (the Squanderfield name so proudly touted and dearly bought in Plate 1, has died out, and because she bears the consequences of her father’s carefree nature in her bowed legs (a brace is visible under her dress) and the sinister black patch on her cheek. (Graphic 274)

Thus, the traditional fear of the adulterous woman and the indeterminate paternity of her bastard children is thwarted here. The licentiousness of the aristocratic father has crumbled the family line and, in a larger message, the licentiousness of English aristocrats has eaten away at the foundations of England, has withered its proud familited and has penetrated and corrupted even the middle classes.

But it is never that easy—the young Squanderfields are, after all, in Paulson's words, "destined to become what they are, formed by their parents and their respective societies" and he notes the couple's comparison to "chained dogs and martyred saints" (Life vol. 1 484) Thus if anyone is explicitly blamed, it is their parents. The countess's father, who was so concerned with achieving social status that he pawned his own daughter, is here unconcerned with the sad scene, removing the wedding ring from his child's finger to preserve, at least symbolically, the alliance, as well as to keep the jewelry out of the hands of the state. Outside, the city is crumbling, revealing Hogarth's true culprit in the condemnation of a society which prizes titles and fortunes above the happiness of its members. Ronald Paulson comments that Marriage a la Mode makes more of an indictment of society than "A Harlot's Progress," where both the individual and society are condemned, because "one feels that the two protagonists were destined from the start to become what they are, formed by their parents and their respective societies” (Life vol. 1 484).

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 6

Shesgreen, Sean. Engravings by Hogarth. (1973)

Her husband killed and her lover hanged, the Countess, returned to her father’s house, is driven to suicide by the tragic consequences of the foolish and ill-fated venture perpetrated on her.

Plainly dressed, she expires on a chair as an ineffectual physician scurries away. On the floor lies a bottle of “Laudanum”; next to it the precipitating cause of her suicide, “Counseller Silvertongues last Dying Speech.” As her impassive, mercenary father, anticipating her burial, dispassionately removes the ring from her finger, a withered old nurse holds her daughter to her for a dying kiss. The crippled girl has inherited both her father’s venereal disease and his beauty spot; since the young Earl has no male child, his family line has ended. The apothecary, who has a stomach pump and a “julep” bottle in his pocket, points to the empty laudanum bottle, and berates the servant who looks at it uncomprehendingly. The fellow, who wears his master’s ill-fitting coat buttoned askew, is an idiot hired cheaply by the alderman.

The house reflects the alderman’s miserly life style, which has supported his costly and tragic manipulation of his daughter’s life. A dark apartment with bare floors and cobwebbed windows with broken panes, it is located near London Bridge, which at that time had houses built across it. On the wall hangs the alderman’s robe, a clock with its figures reversed (it should be 1:56 P.M.) and an “Almanack.” Three “Dutch” paintings (really satires of Dutch realism) decorate the walls; the first (unframed) depicts a man urinating; the second is a still-life crowded with “low” objects (an arbitrary collection of kitchen utensils, jugs and food); the third shows a drunkard lighting his pipe from the swollen nose of a companion. In the alderman’s cabinet stands a single liquor bottle, some pipes and a library of five books; four are financial records: “Day Book,” “Ledger,” “Rent Book” and “Compound Interest.” The hall is lined with fire buckets.

From the meager fare on the table, a skeleton-like dog steals a lean pig’s head.

The painting used as the source of this work is largely identical to the engraving; the differences are mostly technical. The series hangs in the National Gallery, London (56).

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 6

Uglow, Jenny. Hogarth: A Life and a World. (1997)

The crisis is followed by a second tragedy. Distraught at the account of the execution of Silvertongue which she has seen in the broadside dropped at her feet, the Countess has drained a phial of laudanum. Her head is thrown back. Her feet, in their elegant buckled shoes with modish up-turned toes, stick out like a stiff, pathetic reminder of the vivacious, yawning, saucily alive woman who smiled over tea and toast. A maid brings her child to kiss the mother's corpse, but the patch and the leg irons show that the infant is already riddled with syphilis. Shockingly, the grim comedy of life goes on. The apothecary, stomach pump in his pocket, shakes the dimwitted servant who bought the poison. And even while the doctor is disappearing through the door, the merchant glumly eases off the wedding ring to save the gold before his daughter's fingers stiffen.

While the Earl's death is almost Romantic in its extreme poses and intense expressions, the final scene has a horrifying realism. Hogarth put aside the Italianate grandeur mockingly appropriate to the aristocrat and the duel, and turned to the Dutch tradition, where comedy and pathos meet. He closed the circle in the Alderman's house with its view of London Bridge, balancing the opening scene in the Earl's house, with its glimpse of the Italianate mansion. The French lavishness of the aristocrat's world is countered by the merchant's bare boards, miserly meal and scrawny dog. The price of the contract the two men made was the death of their children, the squandering of fortune and the loss of inheritance - the diseased child will be the last entry on that branching family tree (383-384).

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 6

Paulson, Ronald. Hogarth’s Graphic Works. (1965)

As it began in the Earl’s home, the series ends in the merchant’s, contrasting the wasteful pride of the one and the stingy squalor of the other. The pictures on the walls have been an important element of each plate, contrasting the dark paintings of the connoisseur Earl, the erotica of the young couple, the pompous decorations of the brothel, even the images of man shown in Misaubin’s museum. Now the merchant’s tastes appear in the small Dutch still life and vulgar genre paintings. One shows a boy making water against a wall, another two smokers (à la Brouwer), one lad lighting his pipe from the red nose of the other. The rest of the furnishings are similarly typical: the arms of the City of London on the window pane (the view of Old London Bridge through the window), the "ALMANACK" on the wall, the books in the cupboard ("Day Book," "Ledger," "Rent Book," "Compound Interest"). We are back in the world of A Rake's Progress, Pl 1. The window panes are broken and unrepaired, a cobweb appears in the casement, the food is meager and the dog starved (cf. the cat in Rake, Pl. 1), there is no carpet, the ceiling is stained and dirty, the walls bare, and the ledgers are turned with their backs to the wall to save wear and tear. As J. Ireland points out (2, 53), "The scantiness of his own table is well contrasted by the plenty exhibited in the picture" on the wall. The gown hanging on the wall near the clock shows that the merchant is an alderman. His sleek appearance, contrasted with the meager fare he serves, implies that he spends much of his time at the famous City feasts. The clock's face is reversed in the print; it should read 1:55.

Silvertongue has been hanged for the death of Lord Squanderfield. A paper with gibbet and portrait, inscribed "Counsellor Silvertongues last Dying Speech," lies on the floor next to a "Laudanum" bottle, which tells the rest of the story. The Countess has taken poison, and the print shows the reactions of those surrounding her. Her father prudently removes the wedding ring before rigor mortis sets in; the doctor (with doctor's wig and cane) leaves through the door, having given up the case as hopeless. A line of numbered fire buckets hang from the hall ceiling, such as often appeared in merchants' homes before the advent of fire engines.

The Countess' child is significant both because she is a girl (the Squanderfield name, so proudly touted and dearly bought in Pl. 1, has died out), and because she bears the consequences of her father's carefree nature in her bowed legs (a brace shows under her dress) and the sinister black patch on her cheek (reminding us of the father's beauty patch). Stephens (BM Sat.) suspects that the patch covers a venereal sore and also points to her concave profile.

The apothecary, raging at the old servant who procured the laudanum for the Countess, has a syringe that is probably part of a stomach-pump, and a "julep" bottle in his pocket. The servant wears an over-sized cast-off coat of the merchant. His expression-the eyes and the gaping mouth-echoes that of the Medusa in the first plate (and in the Caravaggio painting to which Hogarth alludes); the only difference being that now the expression denotes terror and lack of comprehension of anger (274-275).

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 6

Dobson, Austin. William Hogarth. (1907)

The last scene shifts to the old home in the city, to which in her dishonour, the Countess has returned. Through the window we see London Bridge, with the tottering houses upon it which were taken down in 1756. Counsellor Silvertongue has been hanged at Tyburn for murder; his “Last Dying Speech” is on the floor. The Countess has poisoned himself with laudanum fetched by a half-witted serving-man and a whimpering nurse, with puckered, anile face, holds up a rickety child to kiss the yet warm of its mother (Sala, in an interesting paper in the Gentleman’s Magazine on George Cruikshank, notes that the poor child is a girl. The Earl is the last of his race in the male line, and the title is therefore extinct. This is one of those subtle touches which, except in Hogarth, we may seek for in vain). Meanwhile, the hastily-summoned physician, powerless in the circumstances, majestically quits the apartment; the baulked apothecary bullies the imbecile messenger, and the alderman (careful soul!) with prudent forethought draws a valuable ring from his daughter’s finger before it stiffens with the rigor mortis (80-81).

In the death of the Countess again [Hazlitt] speaks thus of two of the subordinate characters: “I would particularly refer to the captious, petulant, self-sufficiently of the Apothecary, whose face and figure are constructed on exact physiognomical principles; and to the fine example of passive obedience and non-resistance in the servant, whom he is taking to task, and whose coat, of green and yellow livery, is as long and melancholy as his face. The disconsolate look and haggard eyes, the open mouth, the comb sticking in the hair, the broken gapped teeth, which, at it were, hitch in an answer, everything denotes the utmost perplexity and dismay” (82-83).

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 6

Quennell, Peter. Hogarth’s Progress. (1955)

Eventually, disgraced and widowed, the Countess retires to her father’s house. It is on the northern bank of the Thames, probably near Fishmongers’ Hall; Old London Bridge, still crowded with dilapidated Elizabethan buildings, appears in the frame of an ancient leaded casement; but, although the merchant’s parlour may strike us to-day as having a pleasing air of picturesque antiquity, to an observer of Hogarth’s period it was merely bleak and squalid. In these uncongenial surroundings, the Countess, having just read Counsellor Silvertongue’s “last dying speech”, takes a fatal dose of laudanum. The doctor, who has washed his hands of her case, stalks off, nuzzling his stick, on an old-fashioned wooden staircase, lined with clumsy leather fire-buckets; the apothecary abuses her messenger; and the merchant, stolid and practical as always, sets to work removing her expensive diamond ring. The old nurse, the child and the moribund woman provide a splendid central group. Hogarth seldom came closer to the heart of tragedy than in his picture of the little crippled girl, who wears a heavy leg-iron, being lifted up, blubbering and fearful, towards her mother’s livid face. Since she is a girl, the title is extinct: such are the Dead Sea fruit of Marriage-à-la-Mode. But with almost equal delicacy and zest Hogarth has depicted the apparatus of the merchant’s meagre breakfast-table—the sheen of the plates, the glitter of a polished knife, the oily lustre of an earthenware jug and the flaccid texture of boiled meat (176-177).

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 6

Paulson, Ronald. Hogarth: His Life, Art and Times. (1971)

And the series is about both the married couple and the fathers, who hang like malign presences over the plates in which they do not appear: the earl as we learn of his death, which prevents his deriving much benefit from the marriage he has arranged, and as we see his line dying out in the last plate in the syphilis-tainted girl child; the merchant as we see him in the last plate pulling off his daughter’s wedding ring before rigor mortis deprives him of this meager salvage from a disastrous match (vol. 1 484).

The first shows the earl’s quarters with the old masters he collects, pictures of cruelty and compulsion from which his present act of compulsion naturally follows, his portrait of himself as Jupiter furens, and his coronet stamped on everything he owns. . . . Then follows the empiric’s room, with his mummies and nostrums; the countess’ boudoir with her pictures of the Loves of the Gods and the bric-a-brac she bought at an auction, including Romano’s erotic drawings and a statue of Actaeon in horns; and the merchant’s house with its vulgar Dutch genre pictures, meager cuisine, and worn furnishings. Here art has become an integral part of Hogarth’s subject matter: it is here for itself, a comment on itself, and also on its owners and on the actions that go on before it. In no other series is the note so insistent . . . it dominates every room, every plate. The old masters have come to represent the evil that is the subject of their series: not aspiration, but the constriction of old, dead customs and ideals embodied in bad art. Both biblical and classical, this art holds up seduction, rape, compulsion, torture, and murder as the ideal, and the fathers act accordingly and force these stereotypes on their children (vol. 1 488-489)..

The trends toward art as theme and reader as active participant are further underlined by the importance placed on viewing. . . . only in Plate 6, when it is all over, are the pictures unconcerned—the Dutchman turns his back on the scene to relieve himself as the doctor walks away, having given up the case (vol. 1 489).

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 6

Lichtenberg, G. Ch. Lichtenberg’s Commentaries on Hogarth’s Engravings. (1784-1796). Translated from the German by Innes and Gustav Herdan (1966)

We have seen the crimes with some of their non-judicial consequences. The nobleman in his blood, the murderer in his shift escaping into the winter night, and his aider and abetter similarly attired, in the grip of her conscience. The punishment so far was light. Here in this picture it grows to a terrific intensity for both of them, to the highest pitch it can attain, judicially and non-judicially, this side of the grave.

Immediately upon the physical death of her beloved lord and master, and her own moral death which was bound up with it, the Countess leaves the fashionable world of the West End and exiles, or rather buries herself, together with her child and its noble blood, in the East End from whence she came, in her father's vaults, not far from London Bridge, which with its buildings is seen here from the window.

Here now, removed for ever from the magic of the heavenly music of the Court and the tumult of Lady Townley's and Lady Heathen's Drums .and Lady Hairbrain's Rout, she had had the opportunity of making an acquaintance which might have been of infinite advantage to her had it come in better times—that is, with her own self. But it was much too late? Announced by a peal of thunder from her conscience, she appears to herself now for the first time. What a sight! Rejected in the West End by everybody for whose sake she had rejected many another in the motherly East End, and now herself rejected by these same rejected ones, without visits and even without visiting cards, without rank and, finally, without honour she is now the mockery and the derision, the talk and the news, of the first city in the world. Ever more clearly, she recognizes herself at last as the murderess other husband; though not legally hangable, yet extra-judicially condemned to hang herself, towards which end one might, in solitude and ineradicable shame, make very rapid progress. 'Struth! Thus to await the coup de grâce from one's own hand is infinitely more painful than the rope which the law, by God's grace, ordains inevitably for the criminal.

Meanwhile, a feeble ray of hope still shone into her prison. Silvertongue, though arrested and imprisoned, was still alive then, and knew the wrong as well as the right side of the law; what more does such a bird need in order to escape from any cage, by the power of the beak, or the gab? Thus, there was still the possibility that these two gallows-birds, even if not in the East or West End of the city, at least in some corner of the earth, east or west, might build their little nest once more. Soon after, however, Silvertongue is brought to trial, is found guilty and condemned to death by hanging. It was a very great step to take all at once on the path lawful; suddenly one had reached the final stage. The unadorned wooden portal with its entrapping noose through which the way led was close at hand. She still comforted herself: 'It's impossible—he cannot be hanged—he was too dear to me! Surely my departed husband was more to blame. Always drunk, always with his plasters and his pills! He should have looked after me better. Not to steal when some lovely object lies about in the street is not in human nature, any more than it is in human nature to let oneself be stabbed to death for nothing, if one carries a sword. And these, after all, were the only crimes of my Silvertongue. Oh! yes, there is justice in England, but there is mercy too. This, this is what I seek; this is my comfort; justice, but mercy too. Oh! certainly mercy. My Silvertongue lives and will live.' With dreams like these she was still deceiving herself this very morning when suddenly an event occurred with the most terrible effect upon the dreamer. It was nothing less than the thunder-clap: 'No, your Silvertongue will not live, and does not live any longer. This morning, at the stroke often, he was left hanging in the portal's noose; you can see him swinging there still, if you like.' That event we shall now report to our readers in simple prose.

This morning, as the lady might have known very well from the newspaper even if she had not heard it elsewhere, was the day appointed for the execution of her lover. Not being familiar with the fine points of the law, she thought she could easily remember similar, or at least apparently similar, cases, where a comparable crime had been punished merely by imprisonment or transportation. Upon this she based her not altogether impossible hopes, which love and wishful thinking raised now as if by magic power, to certainty. Thus, to make that certainty doubly sure and with the utmost despatch, she sends a sort of Boots (the thing over there by the table that has concealed itself in a man's coat) to the place of execution. That poor devil now brings, perhaps without knowing just what he has brought, not only the news that Silvertongue has just exchanged the temporal for the eternal, and the legal collar of cambric for the hempen one, but in addition a forget-me-not leaflet which we see there on the floor, lying beside an empty medicine bottle. This document, whose seal nobody would easily mistake if he has some human feelings, contains nothing less than Silvertongue's swan-song from beneath the gallows his gallows sermon. This was too much for a tender heart. Her husband- that could have been endured, but her lover! Quick as lightning she grasps a two-ounce bottle of laudanum, which she had evidently prescribed for herself m the first wild moments other newly-gained self-knowledge but found somewhat too powerful when it arrived—and drains it to the last drop. At lunch, the action of the poison becomes apparent; she falls back- wards with her chair; they pick her up, carry her to the armchair, call the doctor, call the apothecary, and a good proportion of his drugs; all arrive but it was too late; had Silvertongue himself been alive and, in a flash' appeared with a ball ticket, he could not have restored her. That it is too late may also be seen from the fact that the doctor is warily with- drawing to pay his respects to the departing soul before the front door This is a brief sketch of the scene which we shall now describe in more detail.

She dies in an armchair with the insignia of the disaster which has befallen her, poison bottle and gallows, at her feel—and thus Squanderfield is at length avenged. An old housekeeper, whom Nature had painted greyer than grey probably twenty years ago already, holds towards the doomed woman the child whose rattle we have seen before, hanging from a chair of a different type. This picture of despair puts its small rickety arms round her neck, and kisses the pallid cheek of the human form that was called mother, but who has never been much more of a mother than she is now, when feeling has left her for ever. On its cheek the poor creature already carries the seal of Squanderfield's blood, and delicate and light though the little body is, she already needs, as we can clearly see, laced boots with steel supports, to prevent the emaciated little legs from bending under their paper-light load. Throughout this scene, which could hardly be more movingly conceived, the old father remains as calm as if the whole daughter had been insured, apart from her rings, which latter, therefore, he takes care to salvage personally. The philosophical composure of that man is really incredible. If our readers will take the trouble to cover the left side of this stoic with a piece of paper so that its edge passes down his right cheek and the extreme tip of the thumb of his right hand, then in describing his movement they will find themselves at a loss to say immediately whether he is filling a fresh pipe, or cleaning out an old one in order to fill it. He receives this secondary punishment from Heaven as he probably received the primary also—with as much composure as if it were merely a bill of lading. What a granite-like imperturbability in that figure there, from the broad, cautious brow, which seems strong enough to resist a hatchet, to the two Stock Exchange flagstone-rammers which, in their sturdiness, seem to put in the shade even the timbered double footgear of the chair in which his daughter dies! And all that close to the corpse of his only child, and having taken her cold hand in his, not in order to press it once more, but to prevent her perhaps from bestowing unawares a ring on the woman who is to lay her out. Surely not even an elephant or a poodle would do such a thing; it could only be the work of all-embracing avarice. The interpreter of this Plate has often found confirmed in real life what Hogarth is trying to teach here: namely, that a certain collector mentality, better a sort of hamster instinct, intent upon saving every year certain 'little round sums' as these people modestly like to call them, by and by overcasts the heart of man with a good, strong callus, which protects it as surely from all moral warmth as soft swansdown protects the chest from physical cold; nay, finally invests its owner with the enviable faculty of bearing every misfortune of his fellow-men, as Swift puts it, with Christian composure. Incidentally, one notices, especially if one has a cold, how carefully that sort of person, or whatever it is, knows how to combine his Horatian aes triplex circa pectus with the homespun pannus triplicus circa stomachum. He wears three coats; for in those happy days a coat and a waistcoat still stood al pari, just like stocks and shares. One can see the man gives nothing away, neither money, nor affection for his fellow-beings, nor animal warmth; of all this he saves as much as possible. The chain under the girl's cold hand is not one of his daughter's bracelets, but the golden chain of office which the old man wears in the house, evidently so as not to leave it with the coat in the counting-house quite by itself, for obvious reasons.

Behind the old gentleman, and apparently garbed in mourning-black, stands a man upon so sturdy a pedestal of calves that it almost seems as if Nature had ordained him for a butcher, and while shaping him had taken into consideration the quarters of oxen which he would have to carry. Nature has, however, made a mistake this time. The man merely became an apothecary, who visited patients, prescribed and dispensed as well, and in the end had the four quarters carried away by others. That he is somebody of this sort can be recognized from the pharmaceutical extinguishing apparatus which sticks out of his pocket, a small squirt and a bottle of julep; the obliging man arrived here, however, only when the building was already burnt to ashes. With his left hand he grips—and with just such a grip as in former times the terrorist Gassner used to grasp the foul fiend— a rather loosely hanging State-livery by the collar, evidently in order to drive out of it the poor devil by whom it is possessed ad interim. It really looks as if the conjuring had had some effect, for if I read the face of the exorcised aright, it seems to express, apart from great anguish of heart, some indecision whether to jump out of the top of the coat or to dive down and slip out below; just as the devil did with Gassner. The story is as follows: the poor soul there, as we have already heard, is some kind of servant in this household, a miserable creature who evidently serves for half-wages, but who also has nothing more important to do than to run as quickly as State-livery permits as soon as anybody calls apporte. This innocent domestic animal has, unfortunately, also fetched-and-carried the poisons which lie on the floor here, side by side, the dying speech and the laudanum. 'See what you have done there, you gallows' bird,' thunders the apothecary, pointing with his right hand at the poisons. 'Who asked you to do that? You deserve to be strung up yourself this very moment, you scoundrel.' With that, he shakes him furiously with his left hand and bestows on him a look which hardly leaves him in any doubt as to what the right hand is going to do the next moment. And the poor sinner who outside on the bridge would not have felt the slightest guilt, now in the claws of terrorism begins to believe, from intimidation, that he really deserves the gallows. Therefore the despair, and the mouth which seems to attempt something like a last dying speech. Is there anything one cannot make the Lord of the Earth and the Inheritor of the Kingdom of Heaven believe if only one can get him properly by the collar and shake apart his store of ideas to suit one's purpose? Then he will do and think and even feel just what is required of him. What a wise provision of Nature! How, otherwise, would it be possible to lead whole millions of such inheritors and guide them where they ought to go? But by this method their mind in the end feels the fist on the collar and its steady force just as little as their body the pressure of the air. Thus, with a sort of rapture, man perceives his name right at the top of Linnaeus's 'Who's Who', and even the monkeys tremendously far below him, without considering that by far the greater part of his species stands, according to a different, but perhaps more rational, system, below the dogs and the millers' donkeys.

The contrast between the two individuals is marvellous. The apothecary's expression, pure, genuine metal, full of bull-like force and resolution; the servant's like a miserable milksop's; his whole head, though not badly equipped, exactly like that of a sheep with St Vitus's dance; trembling, actively determined on nothing, passively open to anything. Oh, whatever becomes of the poor devil, he will certainly not make an Orateur du Genre Humaini! The coat of the one almost like a waistcoat, and even buttoned up, so as not to obstruct the play of his knees as he walks the streets on his salutary visits; that of the other much—oh, much—too long! A proper locking device for the fetch-and-carry, especially if the magazine pouches on both sides are well loaded; a true Spanish mantle. Moreover, the garment of the first sits firmly, not a cubic inch left vacant; everything is stuffed full; only one more pound of pudding and the seam will burst or the buttons fly. But the other's coat, oh gracious goodness—barely half-inhabited, with space enough and to spare to accommodate the whole pound of pudding together with the apothecary. There are certainly no buttons flying off there; they would even slip out of their buttonholes had they been fastened symmetrically; but they are buttoned up askew, and the tenth button is really poking out of the ninth buttonhole, and the eleventh out of the tenth, and so on. The device is not a new one, but if the poor devil has hit upon it himself, he has really displayed some talent for mechanics. For now the button side of the coat does not quite match the buttonhole side, but the former hangs on the latter; it is carried by it. If we now assume that the pocket on the button side will always be specially well loaded as a man's usually is, then if, for instance, when fetching bread the excess weight were only six pounds, the button can as little slip out of its hole as a nail on the wall out of the loop by which a coat hangs on it, no matter how wide the loop may be. The apothecary's stout leg pedestals we have already passed under review. The legs of the servant with the permanent curtsy of impotence which they are in the act of making, hardly deserve the name of legs and are altogether not worth mentioning. Thus only a few words more about the coat. This State- and everyday-livery is really an ancient servants' fief in that family, which at every change of personnel, at every sloughing, always reverts to the feudal lord. Now since under this procedure some saving will obviously be made in the course of time, they have been generous at the start with the material, and everything is rather strong and in full measure, so that it could be partly worn and partly dragged along by any man from 4 ft. 6 in. upwards to a height where he could perhaps let himself be seen for money. That one man will not be as well fitted as another is of course true, but this also applies to a certain extent, not only to their garments, but also to their—services.

Before we turn to a closer examination of the room and its appointments we cannot let the doctor in the doorway there get away without a few more farewell lines, little though they may benefit him. There is some- thing comic about this figure which can be more easily felt than described. Few have looked upon the retreat of the doctor without a smile, but wherein the ridiculous part really consisted, they could not explain to themselves. It is true that the broad knot-wig, the sword hilt in the coat slit, and the Spanish cane with its golden knob, held somewhat below its centre of gravity and gently raised in meditation towards his mouth, have a solemn but incongruous air. But is that all? Not quite. It seems to me that the man's appearance obviously suggests the idea of belated arrival, or the so-called race against time, a situation which in any case is extremely uncomfortable, but is absolutely deadly to an intended impression of solemnity. To be late, even when one is not to blame for it, does not specially become anybody, and can make one ridiculous if it is made with an air of punctuality. Moreover, the best of doctors does not cut a particularly good figure vis-à-vis a dead person whom he had hoped to save; for although, on the one hand, one knows very well and readily admits that the art of medicine is nothing less, and could and should be nothing less, than the art of making man immortal, yet one could not, on the other hand, take it in ill part if some people in such a situation should think that not to be able to help is an art which others could also practise. To evade such a comparison, or at least to cut it short, his Magnificence the Doctor now sneaks quietly away and leaves it to the less sensitive ear of the apothecary to listen to the mourners' complaints about our lack of knowledge and the fruitless expenses.

Hogarth has covered and hung the old merchant's whole room with very telling traits of the most abominable miserliness and that vulgar lack of taste which always closely attends on greed. The first thing that strikes the eye is the table laid for the mid-day meal. The Frenchman who once translated that term by mal de midi would not have been far out here. There is only one hot dish for the hysterical lady, namely a boiled egg balanced on salt. The rest consists of a dead joint (for there is also a living one here) which was to be picked over today for the last time, and half a pig's head, an animal which in life must have had its food worries and which, after death, through being frequently borne to and fro between larder and table, must obviously have suffered still more through desiccation. Although the palate is, as we see, but moderately provided for, eye and imagination are the more richly feasted. They are catered for by some heavy and ostentatiously magnificent silver plate, and particularly by a view of the Thames. With the latter, the generous man has really been somewhat extravagant today; he has opened both window casements: one would have been enough. There is hardly any evidence of plates for guests except a small one, apparently a family meridometer for soup and vegetables.

What the huge ornamental silver vessel with the handles might contain is difficult to say; that is, of course, as far as one cannot see inside it; for as far as one can see, it is obviously empty. If, as is probable, the sly landlord has made good by the vessel what was lacking in drink, then it might at any rate contain stale beer—and still be an expensive- looking drink. The content of the silver jug on the floor is apparently honest-to-goodness, pure Middlesex 1745 from the Thames. This then is the meal at which death has overtaken the fair guest. Of course the poison was to blame. But indeed, for an appetite and digestive powers such as the policeman on the fifth Plate must have possessed, such a dinner, if repeated for only a few days, would surely have been followed by similar sad consequences. We need only look at the living joint there, the dog! Poor devil! Luckily for him, they are mourning the death of the daughter of the house, for otherwise they would surely have been mourning his to- day. He helps himself without recourse to the meridometer. Well done! There is certainly no one among our readers who would not wish the good animal a happy retreat with his booty. But it is difficult to see how such a retreat is possible, and to devour the booty before the enemy's very eyes is out of the question. To outflank the right wing is entirely impossible; the old man is in command there in person, and with the keen, constant wakefulness of a watch-dog, knows equally well how to guard diamond rings and old joints. It would thus seem more expedient either to out- flank the left wing, where there is at any rate some mutiny, or to break through the legs of the apothecary so as to get in front of the old doctor and the departing soul, on whose discretion he can rely, and thus get ahead of her. Let us hope for the best.

In the magnificent bow window with its stained glass, the domestic dragon with her dust-and-spider broom has evidently gashed in a few ugly ventilation holes which gave the old man an excuse for dispensing with cleaning altogether, lest the whole window be turned into a ventilator. A cross-spider has taken advantage of this peacefulness to spread out her net in safety. In this connection one can hardly fail to remember Churchill's verse in which he describes Scotland, though, of course, with southern, anti-Scottish malice, as the promised land 'where half-starv'd spiders feed on half-starv'd flies'. For in very truth if the alderman does not feed his flies better than his dogs, then the above-mentioned crusader might indeed find itself in the position of its Scottish fellow-knights, since in this household even the skeleton of a dog falls upon the dried specimen of a pig. In the matter of repairing the transient, this man has his own methods. He has not attempted to patch up the window panes, not even with sugar paper, which does not look too bad as a rule, but, instead, he has worked on the backs of the ornamental chairs, and that in a way which does not look particularly well. Our readers will notice that the fallen chair must have had a similar fall before, in which both back supports were broken. These have not, perhaps, been glued on but, at least on one side, been reinforced by a stout splinter, which is really much more solid. As far as the appearance goes, it is certain that the mend will be quite invisible to anyone sitting in the chair, and hardly noticeable to others either. The only questionable point is the lack of symmetry in the patching. Indeed, it seems almost as if the splinter on the right is intended at the same time to cover the fracture on the left, since there the parts seem somewhat out of alignment; it may also be that the fracture is new, and once the chair was on its feet again, that little matter would soon correct itself. Little tobacco pipes are to be seen in various parts of the room, one on the window and even three in the small cupboard which contains the business papers. With such care does this parsimonious creature preserve something which every day-labourer in England throws away after he has used it, since he will get another for nothing together with the smallest drink he orders. But since, if I am right, the water-drinkers get nothing, he might be excused on that account.

The private library consists entirely of MSS: The Day Book, the Ledger, the Receipt Book, and, finally, the thickest of them all1 next to the cupboard door, entitled Compound Interest. The little volume in quarto appears to contain the correspondence from the last postal delivery.

In the lower part of the bookcase, next to the pipes, stands a home-made tobacco pouch made out of a twisted quarto sheet, and, probably, a bottle of ink. Perhaps, however, the bottle contains an ipse fecit for the stomach to take of a Sunday morning in well water. The absolutely taste- less insipidity of this cupboard is relieved, at least from the gable end downwards, by an old inverted punch bowl. Since time, aided by careless- ness, has already, as one sees, cut a second spoon groove in its rim, it seems to rest up there in honourable retirement.

The adornments of the walls are, of course, less showy than those of the Squanderfields under the last two governments, but they are at least English workmanship through and through. The alderman's hat and gown hang on the pegs; next to them an English clock, probably with works of English wood. To judge by the calibre of the bell, its stroke and alarum regulate the business of the house on all floors. The hands point to five minutes past eleven. Dinner at this hour is not the worst institution in this household. Even from a miser it is possible to learn something. Eleven o'clock in the morning is even late for a man who at four is already poring over his rent book. In the West End of the City they sit down to dinner when here in the East End it is already five o'clock. This gives the City of London a moral extension in length of six hours' time, corresponding to 90° longitude. Should it increase still more, which seems very probable, and should the King of Spain start boasting again that the sun never sets on his realm, then every Cockney could confidently reply that his home town alone is already so great that the sun, wherever it may be, always finds some family at dinner.

The remaining decoration consists of three paintings, apart from an almanack stuck on the wall. The originals were not, as one sees, of the Italian school; they were never turned out like that in Southern Europe under a clear sky and on volcanic earth, but in some North- Western corner of our continent on alluvial peat soil and in a somewhat heavy, misty atmosphere. The largest of them contains the portraits—one could not call them speaking likenesses but rather tantalizing likenesses— of a leg of mutton, roasted on the spit, heads of cabbage, potatoes, carrots, onions, etc., all executed so appetizingly that the naked appearance of the pig's head on the table could not compete with them. This is what art can do. In addition, we see here stable lights which lack nothing but oily stickiness, little herring barrels complete apart from the smell, swill rags charming to put in one's pocket, if only they would not seem to drip like real ones.

Almost a quarter of this still-lifeless nature the owner has covered with a live Tenters, and thereby has given that kitchen paradise, so to speak, an inmate. A real masterpiece, this, by that Raphael of the Netherlands. It hangs there above the almanack, apparently in place of a morning devotion for the strengthening of the moral feelings, which, after all, is the purpose of all painting and was especially the whole endeavour of Raphael, the Teniers of Urbino. Even if that purpose should be somewhat out of place here, it is at least possible to test by this item of the morning routine whether one still has some moral feeling. It represents a great empty drinking vessel and another still more roomy, somewhat overfull, which have evidently exchanged their contents. The piece is not a complete Tenters, for in his works one sees at least a great number of faces everywhere. Is it perhaps cut out from a whole canvas, or did it alone survive from some destruction of the rest? This seems to me highly probable, since merely to represent that simple process of filtration of Dutch drinks, even a Dutchman would hardly undertake for the sake of its moral implications. But if it is a salvaged cutting, then it is again queer and contrary to an established procedure that in a wholesale destruction only that figure should survive who at the wall—looks. Above the door hangs the third painting, also of the Bog school. This marvellous picture can bear more than one interpretation. Either one of the figures is burning a nose-wart off the other with his pipe—such a thing might be possible; or Hogarth was thinking of Shakespeare and Bardolph's nose which glowed in the dark like a coal, and the man is now merely re-lighting his pipe at it.

Without my drawing attention to it, the reader will have noticed that Hogarth in his pictures, by means of the wall decorations, pokes fun partly at Biblical murder stories and the subtle obscenities of the Italians, partly at the more peaceful cochonneries of the Dutch. As is usually the case with every man of value, he thinks himself better than anyone else. Bravo! Without such a faith not even a grain of sand can be moved, let alone mountains; so, in Heaven's name let us carry on like that; this procedure is most advantageous to the savings-box of Time and of Humanity.

I return once more to the most prominent exhibit of the lunch-time scene, the view of the Thames. The row of houses which we see are the famous, and ultimately infamous, buildings on the bridge itself, which is 915 ft. long and 72 ft. broad. Before the year 1756 it still had those rows of houses on each side to a depth of 26 ft., so that between them there still remained a 20 ft. broad street. Towards the year 1746 these buildings had become so decayed that the inhabitants of the upper storeys ran the unusual risk of being drowned in the next storm, and the sailors the no less remarkable risk of being killed on board ship by falling bricks and tiles. The leaning of these houses towards the miraculous Hogarth has expressed unmistakably. He did this in 1745, and in the following year Parliament decreed the abolition of these houses. I say decreed, for they were demolished only in 1756. That is how things go in this world. But still Parliament was immeasurably more lucky in its intention with these houses than was Hogarth with the present work. The houses disappeared ultimately; our good man, however, wished to eliminate marriages à la mode, but according to the latest news from England they still exist (139-151).

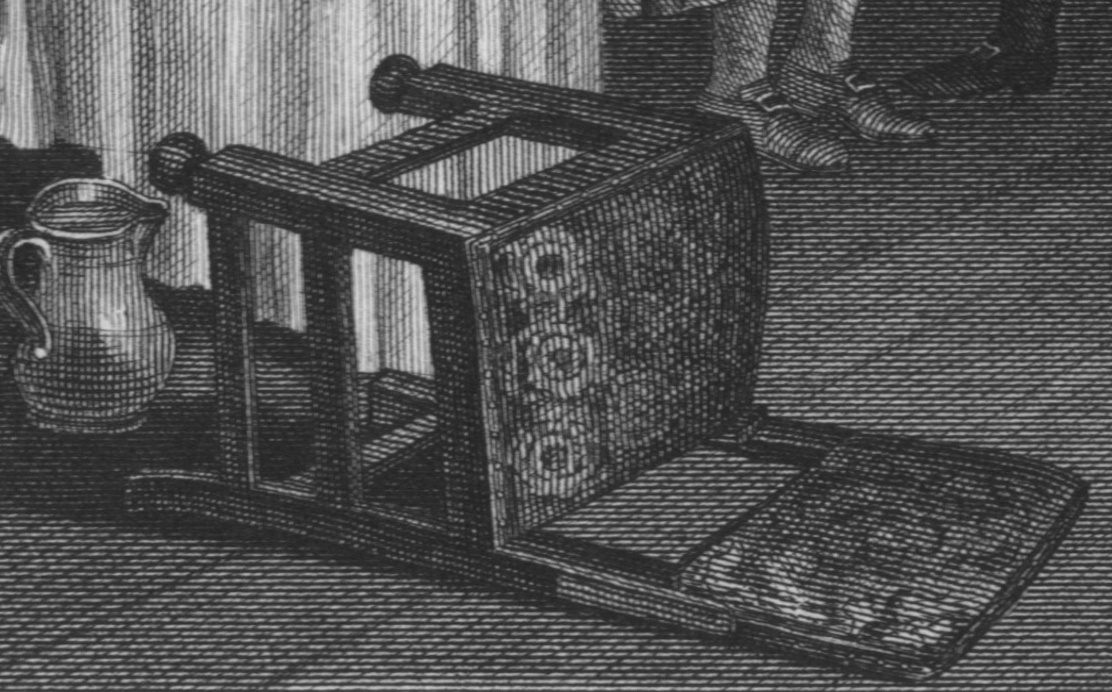

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 6: Chair

The fall is complete, indicated by the fallen chair.

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 6: Chair

Lichtenberg

Our readers will notice that the fallen chair must have had a similar fall before, in which both back supports were broken. These have not, perhaps, been glued on but, at least on one side, been reinforced by a stout splinter, which is really much more solid. As far as the appearance goes, it is certain that the mend will be quite invisible to anyone sitting in the chair, and hardly noticeable to others either. The only questionable point is the lack of symmetry in the patching. Indeed, it seems almost as if the splinter on the right is intended at the same time to cover the fracture on the left, since there the parts seem somewhat out of alignment; it may also be that the fracture is new, and once the chair was on its feet again, that little matter would soon correct itself. Little tobacco pipes are to be seen in various parts of the room, one on the window and even three in the small cupboard which contains the business papers. With such care does this parsimonious creature preserve something which every day-labourer in England throws away after he has used it, since he will get another for nothing together with the smallest drink he orders. But since, if I am right, the water-drinkers get nothing, he might be excused on that account (148).

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 6: Daughter

Here we see the results of the dalliances of the Squanderfields as detailed in Plates 3 and 4. Hogarth's final plate in the series, showing the countess's child caressing her dead mother's face, is one of the truly touching scenes in his work. Her lover and her husband dead, the countess has poisoned herself. The Count has also squandered his fortune, most notably in the promise of a strong family line. In this plate, the couple’s child, female, but more importantly, congenitally syphilitic, becomes an important emblem of waste and despair. This daughter wears a leg brace and a patch—both signs of her only inheritance. Quennell calls the child "Dead Sea fruit" (177), her syphilis, not to mention her sex, determine the end of the Squanderfield line. Jarrett states that there is "a certain divine justice in it all, that although God might visit the sins of the fathers upon the children at least there are sins to be visited" (England 206). The child also redeems the wife somewhat, as she is certainly the daughter of the Lord, resembling him in the legs and in the congenital disease. Paulson notes:

The Countess’s child is significant both because she is a girl (the Squanderfield name so proudly touted and dearly bought in Plate 1, has died out, and because she bears the consequences of her father’s carefree nature in her bowed legs (a brace is visible under her dress) and the sinister black patch on her cheek (Graphic 275).

Thus, the traditional fear of the adulterous woman and the indeterminate paternity of her bastard children is thwarted here. The licentiousness of the aristocratic father has crumbled the family line and, in a larger message, the licentiousness of English aristocrats has eaten away at the foundations of England, has withered its proud families and has penetrated and corrupted even the middle classes.

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 6: Daughter

Shesgreen

Her husband killed and her lover hanged, the Countess, returned to her father’s house, is driven to suicide by the tragic consequences of the foolish and ill-fated venture perpetrated on her. Plainly dressed, she expires on a chair.

A withered old nurse holds her daughter to her for a dying kiss. The crippled girl has inherited both her father’s venereal disease and his beauty spot; since the young Earl has no male child, his family line has ended (56).

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 6: Daughter

Uglow

Distraught at the account of the execution of Silvertongue which she has seen in the broadside dropped at her feet, the Countess has drained a phial of laudanum. Her head is thrown back. Her feet, in their elegant buckled shoes with modish up-turned toes, stick out like a stiff, pathetic reminder of the vivacious, yawning, saucily alive woman who smiled over tea and toast. A maid brings her child to kiss the mother's corpse, but the patch and the leg irons show that the infant is already riddled with syphilis (383).

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 6: Daughter

Paulson, Hogarth's Graphic Works

The Countess has taken poison, and the print shows the reactions of those surrounding her.

The Countess' child is significant both because she is a girl (the Squanderfield name, so proudly touted and dearly bought in Pl. 1, has died out), and because she bears the consequences of her father's carefree nature in her bowed legs (a brace shows under her dress) and the sinister black patch on her cheek (reminding us of the father's beauty patch). Stephens (BM Sat.) suspects that the patch covers a venereal sore and also points to her concave profile (275).

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 6: Daughter

Dobson

The Countess has poisoned himself with laudanum fetched by a half-witted serving-man and a whimpering nurse, with puckered, anile face, holds up a rickety child to kiss the yet warm of its mother (Sala, in an interesting paper in the Gentleman’s Magazine on George Cruikshank, notes that the poor child is a girl. The Earl is the last of his race in the male line, and the title is therefore extinct. This is one of those subtle touches which, except in Hogarth, we may seek for in vain) (80).

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 6: Daughter

Paulson, His Life, Art and Times

And the series is about both the married couple and the fathers, who hang like malign presences over the plates in which they do not appear: the earl as we learn of his death, which prevents his deriving much benefit from the marriage he has arranged, and as we see his line dying out in the last plate in the syphilis-tainted girl child; the merchant as we see him in the last plate pulling off his daughter’s wedding ring before rigor mortis deprives him of this meager salvage from a disastrous match (vol. 1 484).

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 6: Daughter

Lichtenberg

the Countess leaves the fashionable world of the West End and exiles, or rather buries herself, together with her child and its noble blood (139).

She dies in an armchair with the insignia of the disaster which has befallen her, poison bottle and gallows, at her feel—and thus Squanderfield is at length avenged. An old housekeeper, whom Nature had painted greyer than grey probably twenty years ago already, holds towards the doomed woman the child whose rattle we have seen before, hanging from a chair of a different type. This picture of despair puts its small rickety arms round her neck, and kisses the pallid cheek of the human form that was called mother, but who has never been much more of a mother than she is now, when feeling has left her for ever. On its cheek the poor creature already carries the seal of Squanderfield's blood, and delicate and light though the little body is, she already needs, as we can clearly see, laced boots with steel supports, to prevent the emaciated little legs from bending under their paper-light load (141-142).

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 6: Dog

The poor starving dog indicates the miserliness of the alderman. Similarly, in the Rake’s Progress series, the elder Rakewell has starved a cat.

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 6: Dog

Shesgreen

From the meager fare on the table, a skeleton-like dog steals a lean pig’s head (56).

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 6: Dog

Lichtenberg

We need only look at the living joint there, the dog! Poor devil! Luckily for him, they are mourning the death of the daughter of the house, for otherwise they would surely have been mourning his to- day. He helps himself without recourse to the meridometer. Well done! There is certainly no one among our readers who would not wish the good animal a happy retreat with his booty. But it is difficult to see how such a retreat is possible, and to devour the booty before the enemy's very eyes is out of the question. To outflank the right wing is entirely impossible; the old man is in command there in person, and with the keen, constant wakefulness of a watch-dog, knows equally well how to guard diamond rings and old joints. It would thus seem more expedient either to out- flank the left wing, where there is at any rate some mutiny, or to break through the legs of the apothecary so as to get in front of the old doctor and the departing soul, on whose discretion he can rely, and thus get ahead of her. Let us hope for the best (147).

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 6: Men

Shesgreen

The apothecary, who has a stomach pump and a “julep” bottle in his pocket, points to the empty laudanum bottle, and berates the servant who looks at it uncomprehendingly. The fellow, who wears his master’s ill-fitting coat buttoned askew, is an idiot hired cheaply by the alderman (56).

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 6: Men

Paulson, Hogarth's Graphic Works

The apothecary, raging at the old servant who procured the laudanum for the Countess, has a syringe that is probably part of a stomach-pump, and a "julep" bottle in his pocket. The servant wears an over-sized cast-off coat of the merchant (275).

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 6: Men

Lichtenberg

Behind the old gentleman, and apparently garbed in mourning-black, stands a man upon so sturdy a pedestal of calves that it almost seems as if Nature had ordained him for a butcher, and while shaping him had taken into consideration the quarters of oxen which he would have to carry. Nature has, however, made a mistake this time. The man merely became an apothecary, who visited patients, prescribed and dispensed as well, and in the end had the four quarters carried away by others. That he is somebody of this sort can be recognized from the pharmaceutical extinguishing apparatus which sticks out of his pocket, a small squirt and a bottle of julep; the obliging man arrived here, however, only when the building was already burnt to ashes. With his left hand he grips—and with just such a grip as in former times the terrorist Gassner used to grasp the foul fiend— a rather loosely hanging State-livery by the collar, evidently in order to drive out of it the poor devil by whom it is possessed ad interim. It really looks as if the conjuring had had some effect, for if I read the face of the exorcised aright, it seems to express, apart from great anguish of heart, some indecision whether to jump out of the top of the coat or to dive down and slip out below; just as the devil did with Gassner. The story is as follows: the poor soul there, as we have already heard, is some kind of servant in this household, a miserable creature who evidently serves for half-wages, but who also has nothing more important to do than to run as quickly as State-livery permits as soon as anybody calls apporte. This innocent domestic animal has, unfortunately, also fetched-and-carried the poisons which lie on the floor here, side by side, the dying speech and the laudanum. 'See what you have done there, you gallows' bird,' thunders the apothecary, pointing with his right hand at the poisons. 'Who asked you to do that? You deserve to be strung up yourself this very moment, you scoundrel.' With that, he shakes him furiously with his left hand and bestows on him a look which hardly leaves him in any doubt as to what the right hand is going to do the next moment. And the poor sinner who outside on the bridge would not have felt the slightest guilt, now in the claws of terrorism begins to believe, from intimidation, that he really deserves the gallows. Therefore the despair, and the mouth which seems to attempt something like a last dying speech. Is there anything one cannot make the Lord of the Earth and the Inheritor of the Kingdom of Heaven believe if only one can get him properly by the collar and shake apart his store of ideas to suit one's purpose? Then he will do and think and even feel just what is required of him. What a wise provision of Nature! How, otherwise, would it be possible to lead whole millions of such inheritors and guide them where they ought to go? But by this method their mind in the end feels the fist on the collar and its steady force just as little as their body the pressure of the air. Thus, with a sort of rapture, man perceives his name right at the top of Linnaeus's 'Who's Who', and even the monkeys tremendously far below him, without considering that by far the greater part of his species stands, according to a different, but perhaps more rational, system, below the dogs and the millers' donkeys.

The contrast between the two individuals is marvellous. The apothecary's expression, pure, genuine metal, full of bull-like force and resolution; the servant's like a miserable milksop's; his whole head, though not badly equipped, exactly like that of a sheep with St Vitus's dance; trembling, actively determined on nothing, passively open to anything. Oh, whatever becomes of the poor devil, he will certainly not make an Orateur du Genre Humaini! The coat of the one almost like a waistcoat, and even buttoned up, so as not to obstruct the play of his knees as he walks the streets on his salutary visits; that of the other much—oh, much—too long! A proper locking device for the fetch-and-carry, especially if the magazine pouches on both sides are well loaded; a true Spanish mantle. Moreover, the garment of the first sits firmly, not a cubic inch left vacant; everything is stuffed full; only one more pound of pudding and the seam will burst or the buttons fly. But the other's coat, oh gracious goodness—barely half-inhabited, with space enough and to spare to accommodate the whole pound of pudding together with the apothecary. There are certainly no buttons flying off there; they would even slip out of their buttonholes had they been fastened symmetrically; but they are buttoned up askew, and the tenth button is really poking out of the ninth buttonhole, and the eleventh out of the tenth, and so on. The device is not a new one, but if the poor devil has hit upon it himself, he has really displayed some talent for mechanics. For now the button side of the coat does not quite match the buttonhole side, but the former hangs on the latter; it is carried by it. If we now assume that the pocket on the button side will always be specially well loaded as a man's usually is, then if, for instance, when fetching bread the excess weight were only six pounds, the button can as little slip out of its hole as a nail on the wall out of the loop by which a coat hangs on it, no matter how wide the loop may be. The apothecary's stout leg pedestals we have already passed under review. The legs of the servant with the permanent curtsy of impotence which they are in the act of making, hardly deserve the name of legs and are altogether not worth mentioning. Thus only a few words more about the coat. This State- and everyday-livery is really an ancient servants' fief in that family, which at every change of personnel, at every sloughing, always reverts to the feudal lord. Now since under this procedure some saving will obviously be made in the course of time, they have been generous at the start with the material, and everything is rather strong and in full measure, so that it could be partly worn and partly dragged along by any man from 4 ft. 6 in. upwards to a height where he could perhaps let himself be seen for money. That one man will not be as well fitted as another is of course true, but this also applies to a certain extent, not only to their garments, but also to their—services (143-145).

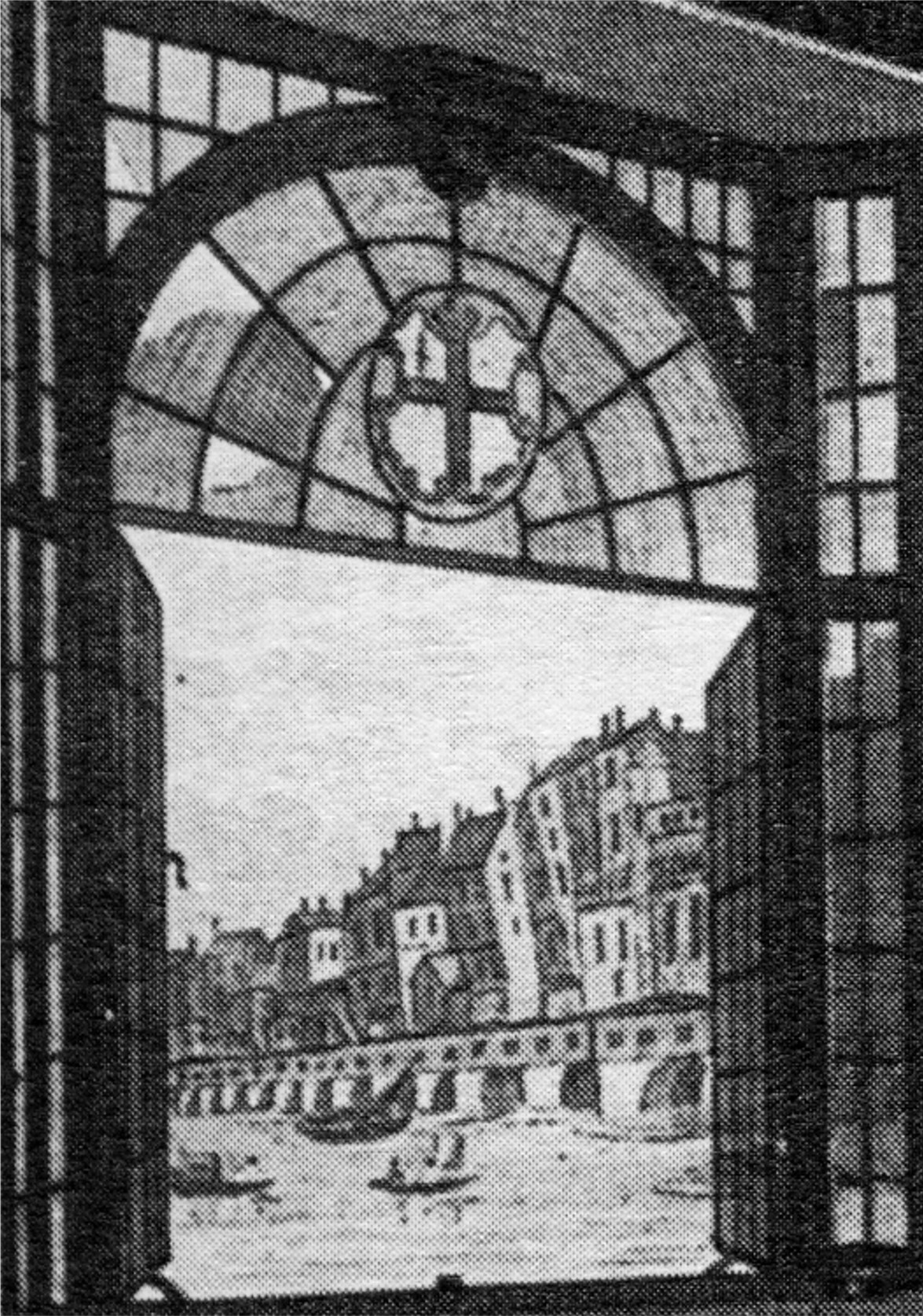

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 6: Outside

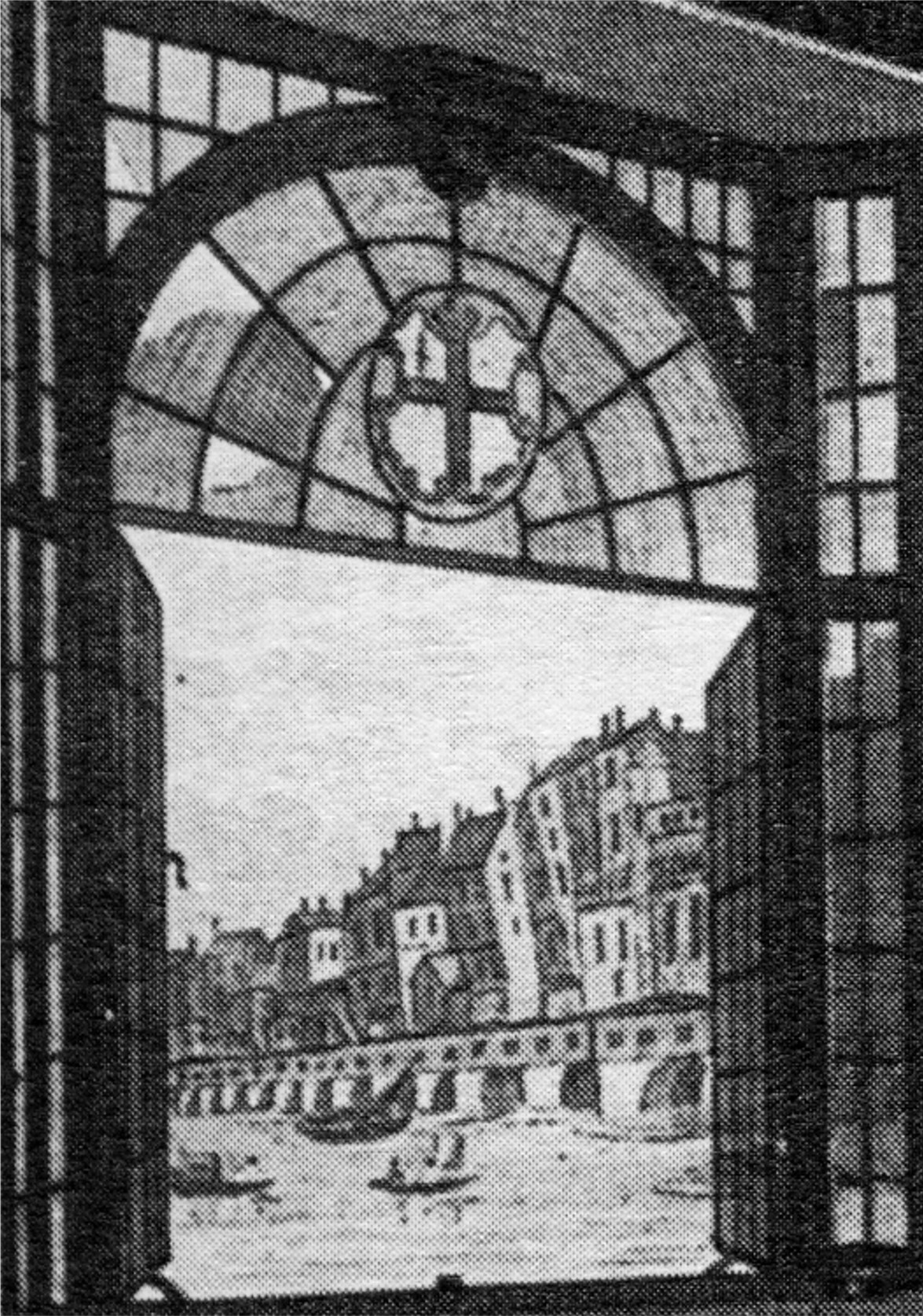

Outside, the city is crumbling, revealing Hogarth's true culprit in the condemnation of a society which prizes titles and fortunes above the happiness of its members. Ronald Paulson comments that Marriage a la Mode makes more of an indictment of society than "A Harlot's Progress," where both the individual and society are condemned, because "whereas the Harlot made her own choice, the individual [in Marriage] is innocent and simply imposed upon."

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 6: Outside

Dobson

Through the window we see London Bridge, with the tottering houses upon it which were taken down in 1756 (80).

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 6: Outside

Lichtenberg

I return once more to the most prominent exhibit of the lunch-time scene, the view of the Thames. The row of houses which we see are the famous, and ultimately infamous, buildings on the bridge itself, which is 915 ft. long and 72 ft. broad. Before the year 1756 it still had those rows of houses on each side to a depth of 26 ft., so that between them there still remained a 20 ft. broad street. Towards the year 1746 these buildings had become so decayed that the inhabitants of the upper storeys ran the unusual risk of being drowned in the next storm, and the sailors the no less remarkable risk of being killed on board ship by falling bricks and tiles. The leaning of these houses towards the miraculous Hogarth has expressed unmistakably. He did this in 1745, and in the following year Parliament decreed the abolition of these houses. I say decreed, for they were demolished only in 1756. That is how things go in this world. But still Parliament was immeasurably more lucky in its intention with these houses than was Hogarth with the present work. The houses disappeared ultimately; our good man, however, wished to eliminate marriages à la mode, but according to the latest news from England they still exist (151).

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 6: Dutch Painting

This random collection of common objects makes light of Dutch painting and mocks the alderman’s taste in art.

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 6: Dutch Painting

Lichtenberg

Almost a quarter of this still-lifeless nature the owner has covered with a live Teniers, and thereby has given that kitchen paradise, so to speak, an inmate. A real masterpiece, this, by that Raphael of the Netherlands. It hangs there above the almanack, apparently in place of a morning devotion for the strengthening of the moral feelings, which, after all, is the purpose of all painting and was especially the whole endeavour of Raphael, the Teniers of Urbino. Even if that purpose should be somewhat out of place here, it is at least possible to test by this item of the morning routine whether one still has some moral feeling. It represents a great empty drinking vessel and another still more roomy, somewhat overfull, which have evidently exchanged their contents (150).

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 6: Bad Painting

A painting of a man burning the nose of another decries both Dutch art and the alderman’s taste in décor.

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 6: Bad Painting

Lichtenberg

Above the door hangs the third painting, also of the Bog school. This marvellous picture can bear more than one interpretation. Either one of the figures is burning a nose-wart off the other with his pipe—such a thing might be possible; or Hogarth was thinking of Shakespeare and Bardolph's nose which glowed in the dark like a coal, and the man is now merely re-lighting his pipe at it (150-151).

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 6: Speech

Silvertongue’s dying speech informs the Countess of his demise. In her despair, she has consumed this bottle of laudanum.

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 6: Speech

Shesgreen

On the floor lies a bottle of “Laudanum”; next to it the precipitating cause of her suicide, “Counseller Silvertogues last Dying Speech” (56).

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 6: Speech

Paulson, Hogarth's Graphic Works

Silvertongue has been hanged for the death of Lord Squanderfield. A paper with gibbet and portrait, inscribed "Counsellor Silvertongues last Dying Speech," lies on the floor next to a "Laudanum" bottle, which tells the rest of the story (275).

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 6: Speech

Dobson

Counsellor Silvertongue has been hanged at Tyburn for murder; his “Last Dying Speech” is on the floor (80).

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 6: Speech

Lichtenberg

This morning, as the lady might have known very well from the newspaper even if she had not heard it elsewhere, was the day appointed for the execution of her lover (140).

This document, whose seal nobody would easily mistake if he has some human feelings, contains nothing less than Silvertongue's swan-song from beneath the gallows his gallows sermon. This was too much for a tender heart. Her husband- that could have been endured, but her lover! Quick as lightning she grasps a two-ounce bottle of laudanum, which she had evidently prescribed for herself m the first wild moments other newly-gained self-knowledge but found somewhat too powerful when it arrived—and drains it to the last drop. At lunch, the action of the poison becomes apparent; she falls back- wards with her chair; they pick her up, carry her to the armchair, call the doctor, call the apothecary, and a good proportion of his drugs; all arrive but it was too late; had Silvertongue himself been alive and, in a flash' appeared with a ball ticket, he could not have restored her (141).

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 6: Ring

The countess's father, who was so concerned with achieving social status that he pawned his own daughter, is here unconcerned with the sad scene, removing the wedding ring from his child's finger to preserve, at least symbolically, the alliance, as well as to keep the jewelry out of the hands of the state.

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 6: Ring

Paulson, His Life, Art and Times

And the series is about both the married couple and the fathers, who hang like malign presences over the plates in which they do not appear: the earl as we learn of his death, which prevents his deriving much benefit from the marriage he has arranged, and as we see his line dying out in the last plate in the syphilis-tainted girl child; the merchant as we see him in the last plate pulling off his daughter’s wedding ring before rigor mortis deprives him of this meager salvage from a disastrous match (vol. 1 484).

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 6: Ring

Lichtenberg

the old father remains as calm as if the whole daughter had been insured, apart from her rings, which latter, therefore, he takes care to salvage personally. The philosophical composure of that man is really incredible. If our readers will take the trouble to cover the left side of this stoic with a piece of paper so that its edge passes down his right cheek and the extreme tip of the thumb of his right hand, then in describing his movement they will find themselves at a loss to say immediately whether he is filling a fresh pipe, or cleaning out an old one in order to fill it. He receives this secondary punishment from Heaven as he probably received the primary also—with as much composure as if it were merely a bill of lading.. What a granite-like imperturbability in that figure there, from the broad, cautious brow, which seems strong enough to resist a hatchet, to the two Stock Exchange flagstone-rammers which, in their sturdiness, seem to put in the shade even the timbered double footgear of the chair in which his daughter dies! And all that close to the corpse of his only child, and having taken her cold hand in his, not in order to press it once more, but to prevent her perhaps from bestowing unawares a ring on the woman who is to lay her out. Surely not even an elephant or a poodle would do such a thing; it could only be the work of all-embracing avarice. The interpreter of this Plate has often found confirmed in real life what Hogarth is trying to teach here: namely, that a certain collector mentality, better a sort of hamster instinct, intent upon saving every year certain 'little round sums' as these people modestly like to call them, by and by overcasts the heart of man with a good, strong callus, which protects it as surely from all moral warmth as soft swansdown protects the chest from physical cold; nay, finally invests its owner with the enviable faculty of bearing every misfortune of his fellow-men, as Swift puts it, with Christian composure. Incidentally, one notices, especially if one has a cold, how carefully that sort of person, or whatever it is, knows how to combine his Horatian aes triplex circa pectus with the homespun pannus triplicus circa stomachum. He wears three coats; for in those happy days a coat and a waistcoat still stood al pari, just like stocks and shares. One can see the man gives nothing away, neither money, nor affection for his fellow-beings, nor animal warmth; of all this he saves as much as possible. The chain under the girl's cold hand is not one of his daughter's bracelets, but the golden chain of office which the old man wears in the house, evidently so as not to leave it with the coat in the counting-house quite by itself, for obvious reasons (142-143).

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 6: Urine

The vulgar painting of a urinating man mocks Dutch art, insults the alderman’s taste in décor and comments on the vulgarity of the situation of the series.

Marriage a la Mode: Plate 6: Urine

Lichtenberg

This seems to me highly probable, since merely to represent that simple process of filtration of Dutch drinks, even a Dutchman would hardly undertake for the sake of its moral implications. But if it is a salvaged cutting, then it is again queer and contrary to an established procedure that in a wholesale destruction only that figure should survive who at the wall—looks (150).