A Rake's Progress: Plate 5

1735

12 1/4" X 15 1/4” (H X W)

Etched and engraved by Hogarth after his painting.

View the full resolution plate here.

The Rake's actions have led him to an unnatural and financially-motivated sham marriage with an aged woman who, as Shesgreen observes, "trades her wealth for sexual fulfillment" (32). This occurs while Sarah and his real, though illegitimate, child attempt to stop the ceremony. The assured barrenness of his current union and the bastard status of his actual child show the breakdown of the family resulting from random sexual misbehavior. Paulson observes that Hogarth also implicates the church for allowing such unions as its "dilapidated condition . . . repeats the physical and moral condition of the pair," also noting a crack in the plaque of the 10 Commandments, carefully observing that this break stops short of the tenth-Thou Shalt Not Covet Thy Neighbor's Wife- indicating that sexual crimes again foremost here (Graphic 166).

Despite the seriousness of the overall theme, the plate is heavy on humor. The two dogs, obviously meant to symbolize the newlyweds, highlight the silliness of the pair’s imminent lovemaking. The male dog has been consistently identified as a likeness of Hogarth’s own favorite canine. Rakewell takes the opportunity to divert his attention to the maid attending his bride. Even on his wedding day, a libertine must maintain his values.

A Rake's Progress: Plate 5

Shesgreen, Sean. Engravings by Hogarth. (1973)

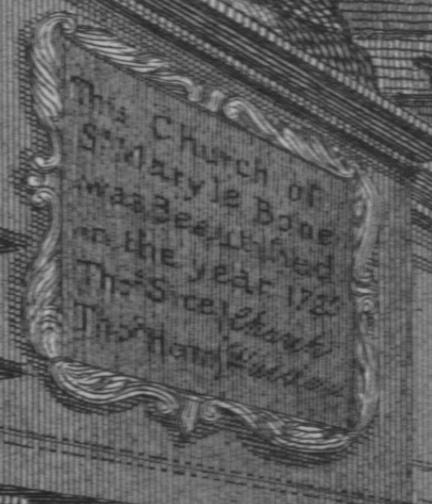

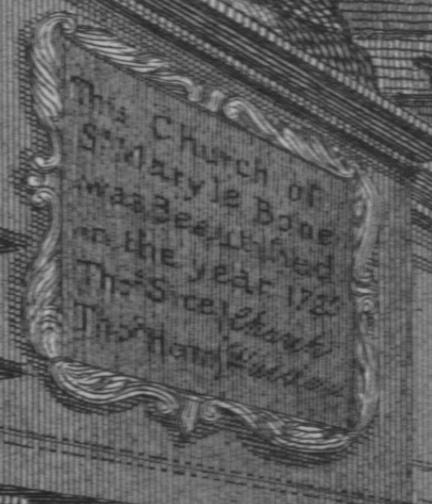

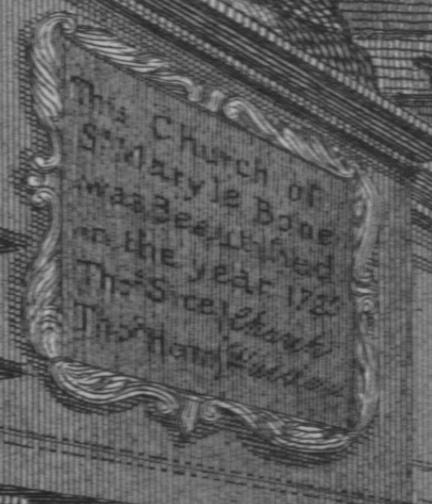

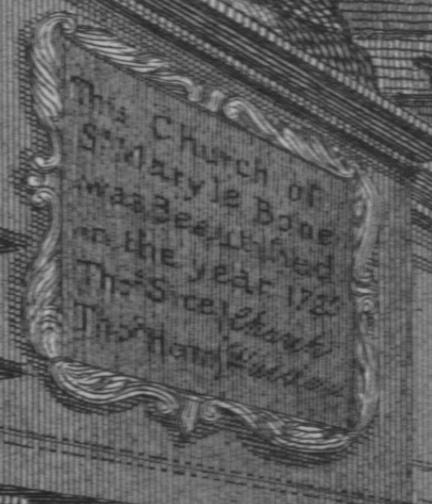

Unreclaimed to bourgeois life by Sarah Young and determined to pursue his career as a gentleman, the rake repairs his fortune by a cynical alliance with an aged, ugly partner who trades her wealth for sexual fulfillment and class advancement. The scene of this mock religious ceremony is the decayed church of St. Mary-le-Bone, famous for clandestine marriages (the gallery holds a plaque reading “This Church of St. Mary le Bone was Beautified in the year 1725, Tho Sice Tho Horn Church Wardens”).

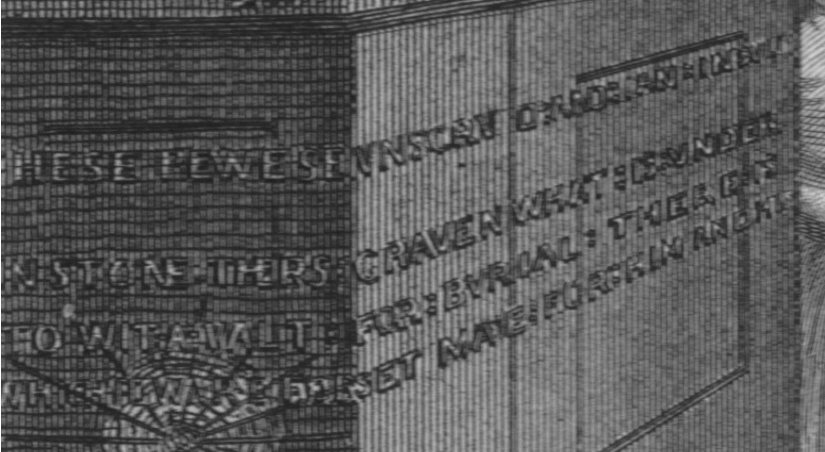

The condition of the church mirrors the nature of the act and actors in the scene; plaster has fallen from the walls; the creed on the right wall has rotted away, leaving only the words “I Believe”; and the tablet with the commandments is cracked. The sounding board behind the pulpit bears the outline of the preacher’s hat. The pew at the left, like clergyman and church, belongs to those who can buy it. The inscription reads: “These: pewes vnscrvd: and: tan: in. svnde[r]/ In. stone: thers: graven: what: is: vnder/ To wit: a: valt: for: bvrial: there: is/ Which: Edward: Forset: made: for: him: and: his.” “The poors box” is covered with a cobweb.

The rake, a stately, attractive figure, is in the act of prostituting himself in much the same way as the harlot did in Plate II. As he slips the ring on his wife’s finger, he glances calculatingly at her young maid. At the feet of these richly dressed figures, a ragged urchin with his toes peeping through his right shoe positions a kneeler for the bride. The wife, an overdressed, one-eyed, hunchbacked creature, leers and seems to wink at the clergyman, a figure much more her match in age and looks. The small crucifix on her breast and the halo-like “IHS” above her head cast her satirically as a saint. A large, aggressive dog and a smaller one-eyed bitch mirror the alliance taking place at the right. In the background a churchwarden battles with Sarah Young and her clawing mother, who have come with the rake’s child to prevent the marriage (32).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 5

Paulson, Ronald. Hogarth’s Graphic Works. (1965)

CAPTION:

New to ye School of hard Mishap,

Driven from ye Ease of Fortune's Lap,

What Shames will Nature not embrace,

T'avoid less Shame of lean Distress?

Gold can the Charms of youth bestow,

And mask Deformity with Shew;

Gold can avert ye Sting of Shame,

In Winter's Arms create a Flame,

Can couple Youth with hoary Age,

And make Antipathies engage.

The central group consists of the Rake's old, rich bride, a bridesmaid, and the Rake himself, whose eye is already on the bridesmaid. In the background the pew opener waves her keys in an attempt to keep out Sarah Young with her baby and her mother, who have come to forbid the banns. The evergreens on the altar are appropriate to the perennial quality of the old woman's lust and (as Hoadly suggests in his verses) to the wintry marriage that this one will be. The encircled "IHS" on the pulpit cloth makes a mock halo behind the old woman’s head, and the two dogs courting offer a parallel to the human situation; like the old woman, the courted dog has only one eye. (The male dog is supposed to be Hogarth's Trump: Gen. Works, 2, 122.) The dilapidated condition of the church repeats the physical and moral condition of this pair. It is Marylebone Old Church, which was almost out in the country and therefore popular as a place for secret or hasty weddings. The inscription on the balcony announces: "This Church of St Mary le Bone was beautifyed in the year 1725 Tho Sice Tho Horn Church Wardens." ]. J. Ireland (I, 48 n., following Biog. Anecd., 1785, p. 217 n.) notes that Sice and Horn "were really churchwardens in the year 1725, when the repairs were made. This print came out only ten years afterwards and the present state of the building seems to intimate, that Messieurs Sice and Horn had cheated the parish, when they officially superintended the affairs of their church." The ragged appearance of the charity-boy, who holds a hassock for the bride to kneel on, comments on his guardians as the appearance of the church comments on Sice and Horn. The Creed is torn (or rotted) so that only the beginning, "I believe, is legible; the tablet of the Commandments from VI through X is cracked--significantly it is the second tablet, which deals with "Duties to our Neighbors." The crack stops short, however, of the Tenth Commandment, which includes "Thou shalt not covet thy neighbor's wife." The opening of "THE POORS BOX" is covered with a cobweb.

The smear-like marks on the back of the pulpit suggest the shape of the squat clergyman's head and shoulders, and above these is a circular mark produced by his custom of hanging his hat on a nail while he preaches (see The Sleeping Congregation). The clergyman who fits these marks is reading the service "OF MATRIMONY," and his clerk stands beside him. The inscription on the pew at left reads: "THESE: PEWES VNSCRVD: AND: TANE: IN. SVNDE[r] / IN. STONE: THERS: GRAVEN: WHAT: IS: VNDER / TO: WIT: A: VALT: FOR: BVRIAL: THERE: IS / WHICH: EDWARD: FORSET: MADE: FOR: HIM: AND: HIS." As Nichols and Steevens explain (Gen. Works, 2,123):

Part of these words, in raised letters, at present form a pannel in the wainscot at the end of the right-hand gallery, as the church is entered from the street.--No heir of the Forset family appearing, their vault has been claimed and used by his Grace the Duke of Portland, as lord of the manor. The mural monument of the Taylors, composed of lead gilt over, is likewise preserved. It is seen, in Hogarth's Print, just under the window. The Bishop of the diocese, when the new church was built, gave orders that all the ancient tablets should be placed, as nearly as possible, in their former situations.

Hogarth's composition-particularly the pose of the bride and groom--is based on Picart's "A Catholic Wedding" in his Cérémonies et Coutumes (reproduced, Antal, pl. 27b) (166-167).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 5

Uglow, Jenny. Hogarth: A Life and a World. (1997)

Tom buys his way out with a furtive wedding to a rich, leering old woman among the cobwebs and cracked Commandments of Marylebone Church, while Sarah, with his baby in her arms, struggles vainly to stop the banns (254).

For his the scene of Tom’s marriage Hogarth drew the dilapidated walls of Marylebone Old Church. The setting was symbolic: the Creed ruined by damp, the Ninth Commandment cracked, the poor box covered by a cobweb. But the inscription on the pews, announcing that the Forset family vault lies beneath, was genuine enough; so was the monument to the Taylors, seen under the window. And so was the inscription on the wall announcing the church “was beautifyed in the year 1725, Tho, Sice, Tho. Horn Church Wardens”. These men really were the churchwardens when the “repairs” were done, and Hogarth need show no more to suggest they had cheated the parish. The crumbling church was pulled down six years later (299) .

A Rake's Progress: Plate 5

Ireland, John and John Nichols. Hogarth’s Works. (1883)

To be thus degraded by the rude enforcement of the law, and relieved from an exigence by one whom he had injured, would have wounded, humbled, I had almost said, reclaimed, any man who had either feeling or elevation of mind; but, to mark the progression of vice, we here see this depraved lost character hypocritically violating every natural feeling of the soul to recruit his exhausted finances, and marrying an old and withered Sibyl, at the sight of whom nature must recoil.

The ceremony passes in Marybone Church, which was then considered at such a distance from London, as to become the usual resort of those who wished to be privately married. That such was the view of this prostituted young man, may be fairly inferred from a glance at the object of is choice. Her charms are heightened by the affectation of an amorous leer, which she directs to her youthful husband, in grateful return for a similar compliment which she supposed paid to herself. This gives her face much meaning but meaning of such a sort, that an observer being asked, “How dreadful must be this creature’s hatred?” would naturally reply. “How hateful must be her love!”

In his demeanour we discover an attempt to appear at the altar with becoming decorum: but internal perturbation darts through assumed tranquility for though he is plighting his troth to the old woman, his eyes are fixed on the young girl who kneels behind her.

A parson and clerk seem made for each other: a sleepy, stupid solemnity marks every muscle of the divine, and the nasal droning of the lay brother is most happily expressed. Accompanied by her child and mother, the unfortunate victim of his seduction is here again introduced, endeavouring to enter the church and forbid the banns. The opposition made by and old pew-opener, with her bunch of keys, gave the artist a good opportunity for indulging his taste in the burlesque, and he has not neglected it.

A dog (“Trump,” Mr. Hogarth’s favourite dog, which has introduced in several of his prints.) paying his addresses to a one-eyed quadruped of his own species, is a happy parody of the unnatural union going on in the church.

The Commandments are broken: a crack runs near the tenth which says, “Thou shalt not covet thy neighbour’s wife;” a prohibition in the present case hardly necessary. The Creed is destroyed by the damps of the church; and so little attention has been paid to the poor’s box, that—it is covered with a cobweb!!! These three high-wrought strokes of satirical humour were perhaps never equaled by an exertion of the pencil; excelled they cannot be.

On one of the pew-doors is the following curious specimen of churchyard poetry and mortuary orthography:--

THESE: PEWES; VNSCRUD; AND TANE; SVNDER

IN: STONE: THERS: GRAUEN: WHAT: IS: VNDER

TO: WIT: A VALT: FOR: BURIAL: THERE: IS

WHICH: EDWARD: FOREST: MADE: FOR: HIM: AND: HIS

(It appears from an examination of the registers, etc. that Thos. Sice and Thos. Horn were really churchwardens in the year 1725, when the repairs were made. This print came out only ten years afterwards; and the present state of the building seems to intimate that Messieurs Sice and Horn had cheated the parish, when they officially superintended the affairs of their church. The coat, shoes, and stockings of the charity-boy convey a similar satire, though that is directed to another quarter.)

A glory over the bride’s head is whimsical.

The bay and holly, which decorate the pews, give a date to the period, and determine this preposterousness union of January with June to have taken place about the time of Christmas, “When Winter linger’d long in her icy veins.”

Addison would have classed her among the evergreens of the sex,

It has been observed that, “the church is too small, and that the wooden post, which seems to have no use, divides the picture very disagreeably” (The Reverend Mr. Gilpin). This cannot be denied: but it appears to be meant as an accurate representation of the place, and the artist delineated what he saw.

The grouping is good, and the principal figure has the air of a gentleman. The light is well distributed, and the scene most characteristically represented (139-143).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 5

Dobson, Austin. William Hogarth. (1907)

Some temporary assistance [for his arrest for debt in Plate IV was] rendered to him by the unfortunate girl whom he discarded in Plate I; but it is only temporary, for in the plate that follows he is repairing his fortunes by an alliance in old Mary-le-bone Church, then much used for private marriages, with an elderly heiress. The bride is one-eyed, and tremulously exultant; the bridegroom, indifferent, and already absorbed by the good-looking lady’s maid. The church, which has been recently repaired, and was taken down altogether six years later, is depicted—no doubt as a fitting background to the bride—in an extremely dilapidated condition. The Creed has been destroyed by damp, and a crack runs through the Ninth Commandment. As a further evidence of neglect the slot of the poor-box is covered by a cobweb (Eighteenth-century churches were often allowed to fall into extremely ruinous condition) (42-43).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 5

Quennell, Peter. Hogarth’s Progress. (1955)

At length, a moment arrives when the Rake must marry; and this he does, choosing as his bride a rich, elderly, one-eyed spinster, to whom he is united in Marylebone Old Church, a tumbledown edifice then almost in the open country, and because of the remoteness of its situation much favored for hasty or secret weddings. Sarah Young does her best to intervene; but she is beaten back by a pew-opener; and Tom, having replenished his fortune, becomes a gambler on a grand-scale (132).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 5

Lichtenberg, G.Ch. Lichtenberg’s Commentaries on Hogarth’s Engravings. (1784-1796). Translated from the German by Innes and Gustav Herdan (1966)

Our hero continues his way through the zodiac of his life. He appears to have made a fortunate escape from the jaws of the British Lion of Justice, and here he is entering the sign of the Virgin (Virgo). The sign itself is depicted, but requires some explanation. Rakewell's paternal fortune has gone, and the whole conglomeration of boxes and cupboards and corners which we saw on the first Plate may still contain many a little trifle for pussy, but alas! no longer anything for him. To fill that terrible void he has opened up in the East End a small bartering business with his manly figure, and this has prospered so delightfully that everything filled up once more. To understand that business thoroughly, one should know that in the orient of London live the true money-planters who concentrate specially upon cultivating its seeds; in the Occident, on the other hand, they are more occupied with the enjoyment of the plant itself, and have so little thought for the future that families often find themselves compelled to obtain fresh seeds from the orient, on stringent terms. It is just such a bargain whose contract is being concluded here; only the conditions are not too strict; he merely has to marry, and the wedding is now being solemnized. Bride and bridegroom have found what they each sought: she a handsome young man, he a rich wife; what more does one want? That neither of them found what they did not seek is nobody's business, least of all a motive for rejoicing in another's misfortune, as I have sometimes found it among people to whom I have shown that wedding scene. But they were quite wrong in this. A sensible man will express his enjoyment of other people's misfortune only if he perceives that they have been deceived in their hopes; but where is anything of that kind here? She did not look for riches and did not find any. And he? He did not look for beauty, and so he found none. On the contrary, he found debts to Nature into the bargain. This is the theme.

That the bride does not, and cannot hope to, find any fortune has been excellently expressed by Hogarth. But how does he show that the bride- groom did not find beauty? For poetic justice to his hero requires this at least. Come, dear reader, and look at the friendly angel who stands beside him; that is what he has found. Now do you complain of the lack of poetic justice? On the contrary, I am afraid your verdict may be: Summum jus, summa injuria. There will hardly be a pair of hungry eyes in the world, even if they were specially trained to look for precious metals, that would not recoil at the sight of that little treasure, just as another pair of eyes on the first Plate flinched before another little treasure box— Ugh! Only guineas! It is too bad. But we shall see.

It has been observed long ago that it would be much better for ladies' adornments, and consequently for the ladies themselves, if they were more intent upon the subordination between their two great dressmakers, Nature and Art. But as a rule the latter, an amiable, ingratiating witch, is mistress of the house, and thus it is not surprising if the other completely withdraws sometimes, or else, when the former has finished with her flimsy work, uncovers with one jerk, but with infinite subtlety, a little spot of contrast, and thereby puts all art to shame. Thus, for instance, the head of the bride would not have been at all bad if she had only let Nature have her way. For though chance has deprived the poor creature of an eye, that in itself would not have rendered her ugly, but now comes die above-mentioned busybody and to improve matters she puts that omission, by means of a few stuck-on beauty-spots, so obviously among the errata, that nobody can fail to detect it at once. I challenge the world to tell me whether the pair of natural eyes that stand there in the face of the bride like an iambus (u -) is one whit more disagreeable than the sly, artificial spondeus (- -) in the face of the bridegroom? Apart from this, one might apply to the remaining eye what the English Aristophanes says about the eye of Lady Pentweazle's great-aunt: 'Although it stands alone, it is a genuine piercer, and procures her three husbands for one.' Also, as it seems to me. Art could have been better advised to leave her mouth as it was, without the quite purposeless u-shape. This is the sign for short syllables. All right; but a mouth cut to the pattern of the sign for short syllables is for that matter not yet a short cut. The whole symbol is no use anyway. Had the first poets understood geometry they, would surely not have denoted the long by the natural symbol for the short, nor the short by the symbol for the curved and the roundabout.

Although, in some respects. Art has been somewhat niggardly in its dealings with that bride, in others it has not treated her quite so badly, and this deserves honourable mention. Thus, for instance, the circum- stance that the lady is almost two feet shorter than her bridegroom, and only four fingers taller than her chambermaid who kneels behind her, is a natural deficiency which has as far as possible been counteracted by Art. It is only a pity that the ceremonial height with which it has endowed the lady is not designed for the still, stuffy air of a village church, but rather for a Zephyr in the Park, or the whirlwind of a waltz at the Ball. We observe that she has the peacock adornment of her lovelier part, I mean the feathered tail of her head-dress, swept backwards. In a storm or a whirl- wind she would float along like a Juno. But though she may add to her stature, thereby, this is neither the time nor the place for it. The words of thunder "And he shall be thy master' could fold up all the splendour of the world, as could rain the loveliest peacock's tail. Some people have found fault with Art for having left the bride's ear so unbecomingly uncovered. Now I cannot see anything in this. I rather find fault with Rakewell's peruquier for having so completely covered up his. At a wedding ceremony ears are more needful than eyes; and then I find the little touch of vanity in a half-blind person, especially one blessed with a somewhat suspect physiognomy, in wanting to show that she has at least both her ears, very natural and human.

But now we come to a major question: is the bride still a virgin?—or more properly, is the bride there a widow or not? A matter which nobody else in the world would trouble about is often of paramount importance to an author, and that is the case with us here. Were she neither virgin nor widow, I would at least have to ask the reader to cut out a line from the beginning of this Chapter where it was said that Rakewell was entering the sign of Virgo. But it can quietly stay where it is. For the benefit of the doubters in such a delicate question a miracle has come to pass, so beautiful that if it is genuine, which nobody could well doubt since it is so beautiful, Madame Rakewell's name would deserve to be honoured in red letters. On the pulpit behind her are the well-known arms of the Jesuits, a sun with the letters I.H.S., which have this in common with the Jesuits themselves, that one can make out of them what one will, provided it is something good. That sign stands here, in full conformity with its meaning, just above the head of injured innocence and thus becomes the Virgin's crown. Yet, what renders this miracle wonderful even as a miracle is that the connection is evident only from the side where we, the doubters and sneerers unfortunately, stand! Just as ghosts are known to appear, in the largest gatherings, only to those whom to convert or to frighten they have left their graves. To believe and hold one's peace is to be wise.

Rakewell's figure is not utterly devoid of grace. One sees that Essex can achieve something when he tries, so can the proposition: 'Quarter of a century younger and two feet taller.' In his eye gleams a sense of superiority coupled with an easy contempt and dissimulation, with a touch of the lover's roguery. Without that touch we could have spoken of Jesuit signs here too. The ears we cannot see and the eyes—only just! But they themselves are keenly focused. Their glance passes right through the bride's halo, without disturbing it, on to a little item from the bride's Inventory, the chamber-maid, who, compounded with the rest of the Capital, has evidently contributed to the completion of the bargain. The girl is occupied in improving something in her mistress's Culotte, the Seraphin being beyond improvement. In the girl's face we notice the trace of a hidden smile, which leads us to think, not without reason, that the parson, in order to make the bride a compliment, has refrained from eliminating certain words from the wedding formula which are usually omitted when the bride is a quarter of a century older than the bridegroom, who is just entering his second quarter.

Before the bridal pair, like two liturgical clocks, stand the parson and the parish clerk; they are both set at 'Wedding', the former being the regulator, the latter the chimer. The English institution of parish clerk is one which will certainly disappear as soon as Herr von Kempelen has succeeded in constructing his talking machine; even now, one would think, a clock that could strike 'Amen' would not be more difficult to construct than one calling 'Cuckoo'. One can almost hear the man bleating his tedious 'Amen'. However, beneath that cold official mien one can still discover a little glimmer of mischief. I fear it is about the semi-secular feast which is here solemnized as if it were a Day of Dedication. About the Pastor, Mr Gilpin observes, quite excellently, that everybody who looks at him thinks that he has somewhere seen such a face and such a wig, but cannot for the moment say where. It would be impossible to praise our artist more highly in so few words. Eyebrows, eye, mouth (sit venia verbo), nay everything down to the very thumbs are cut as if out of one piece. The boy in front of the bride who is occupied in pushing a hassock before her, since the kneeling down is imminent, belongs, as we can see from his little collar, to the Charity School of the parish. His miserable clothes demonstrate that the Director so manages matters that the children do not forget how to beg. One never knows whether they may not need to again. Jacket and stockings are torn, and from the shoes peep not only the feet of the stockings, but the toes themselves. Since, as we shall hear soon, this Church, and consequently the parish, are very clearly indicated, Hogarth must have known whom he had before him when he dealt such blows.

If we let our eyes wander over the whole of this scene, it almost calls to mind the prospect of a harbour on a rough day, where in the foreground ships of all kinds lie peacefully at anchor, whereas near the entrance waves are beating high, making entry difficult for newcomers and dealing blows which, if the ships do not quickly succeed in reaching the open sea, not uncommonly end with the loss of the rigging or even of the cargo and the ship itself.

My readers will have noticed that a violent storm is really raging in the background here. The trouble is briefly this. Sarah Young has saved her abominable seducer by sacrificing her little all. He promised her marriage for the second time and—here for the second time betrays her. She appears here with the child, this time in her arms, to protest against the union of her seducer with another woman. Probably she did all this on the advice other mother who, to judge from her physiognomy, holds somewhat different views about the ways of Heaven than does her good- natured daughter. The latter surrenders to its will in the hope of a better future; the former, on the other hand, is in favour of at least trying whether, by the use of the fists which Heaven has granted her, something might not be done already upon earth. She thus arrives here with her daughter at the harbour, but as she is about to enter, and is already making headway, they are met by such terrific breakers that the daughter is immediately driven out again. The mother, though she tries to battle with the waves, and throws out a five-pronged anchor, finds that such measures cannot help much here and, as we shall see, they have in fact not helped at all. The Sexton's wife, or some other aged pew-opener, well versed in the law of the Church, who may be apprehensive of the Power of the Keys and of the loss of the stole-fees, seizes a bundle of Church keys and, entirely contrary to reason and equity (and specially the compelle intrare), starts hitting out against the two protesting women. The daughter, gentle and yielding and more concerned for her child and her mother than for her own rights, compromisingly withdraws. The mother, on the other hand, takes up arms and defends herself desperately to the last with large and small, though always natural, guns. To understand this classification of natural arms, one must know that in England when men quarrel, they carefully draw in their nails and endeavour with clenched fist, by weight and swing alone, to fell their adversary. But the women on such occasions leave their nails out and try not so much to down the enemy as to bleed him with a ten-bladed scarifier. Madame Young, however, fights here like an Amazon, combining the scarifier with the cudgel, and yet victory is not for her; she has the clergy against her! If from that storm one turns one's thoughts again to Rakewell's face, it almost seems as if he heard and not a little feared its roaring. Apart from him nobody in the whole Assembly seems to pay much attention to it, except perhaps the sole 'dearly beloved brother', the pious listener, up in the Gallery.

From the creatures endowed with reason, of whom we can count here precisely ten, provided, as is only fair, the young child in arms and the old woman in front of the priest, labelled with the I.H.S., are lumped together as one, the transition to inanimate nature is effected most becomingly through the animals not possessing the gift of reason. Moreover, through special circumstances, the gradation here is almost unnoticeable. In the so-called inanimate nature Hogarth's immortal spirit lives and works, and the animals are of a kind whose sagacity would do honour to many a human subject in that congregation—the almost-thinking dog and the geometrizing spider.

On the left-hand side, immediately behind the hassock, is a small tête-à-tête which stands to the main group in this picture in almost the same relation as the Assembly of Black Patricians on the pavement, described above, to that in White's Coffee House. Hogarth's immortal pug-dog called Trump, a lively male, is observed in secret conversation with an elderly creature of his species but of the opposite sex, which deserves our attention for the reason that it is carried on with three eyes only. If we examine the group a little more closely we cannot help arriving at some rather queer ideas, for does it not look as if the little bitch were boasting other white breast, of the little shiny bells round her neck, and of some- thing which looks very much like a small metal plate? And there is really something hanging down behind which would be more suitably paraded in the open air, or at a so-called Wedding procession in the street, than in here. All that is missing is a little bitch to occupy itself with the culotte of the amiable lady, in which case Trump would probably also squint that way, over the head of his beloved, whereby a certain similarity, which we must not proclaim too loudly, would be complete. But no! Trump is honest, and as one can see from his whole attitude, which he has not learnt from an Essex, does not ask for anything to be thrown in.

Close beside the symbolic group we have just described is the Poors' Box, attached to one of the pews. The box must be very poor, or at least visited more by flies than charitable fingers, for a cross-spider has spread its net over it, as one of the safest spots for her in the whole building, and evidently the Elders of the church have let it stay there to save themselves the trouble of fruitlessly opening a box which cannot be rattled in order to verify every morning that none of the contents was missing. This is the only object in the church which would lead us to think that its wardens were still capable of doing something, if they had a mind to. This idea of Hogarth's has become famous, at least I had already heard about it when I was very young. It must have really mattered to the artist that he should be understood, in this case, and that is why he has drawn the threads of the web so strongly that even the most cursory glance remains hanging in the web of that satire lurking in the corner there.

Behind the clergy of the establishment are the Tables of the Law, one of which has a strong crack running through the ninth Commandment (our eighth): 'Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbour.' For the Anglican Church makes two Commandments out of our second, and by way of compensation, one out of our ninth and tenth. From that apparently negligible, theoretical alteration, however, arises a great difference in practice. Every crime in pto. sexti, for which, in the greater part of Germany (where it refers to the relations between parents and children), nobody gives a damn, is in England inevitably punished by hanging, for there it refers to murder. By way of compensation, however, we in Germany, provided nothing untoward happens, hang the trespasser against the seventh (stealing), whereas in England the thief can marry his accomplice (in adultery) and go where he likes.

Next to the Tables of the Law, just behind the Parish Clerk, is a spot where something had once hung which must have been of importance, not because it was behind the clerk's place, nor because a knight's helmet with a lion still hangs above it like an emblem of the knight's virtues, nor because a cherub's head floats above it, but because it had hung next to the Tables of the Law. Luckily for the interpreter. Time's tooth, or more likely Wantonness' claw, or whatever it may have been, has left just enough of it for us to see what it was. There are still upon the precious relic the words 'I believe, etc.' It was thus the creed which used to hang there where nothing hangs any longer. This could be interpreted as: I believe nothing whatsoever, or everything which may be hung there again in the future. It is a pity that the vacuum of faith there has such a very indefinite, frayed edge. In a frame, polished, beautifully gilded, and decorated with all the insignia of philosophy, it would provide the most eloquent symbol of tolerance imaginable. Taking everything together, one could conceive of no church which would combine so little outer charm with so much inner charm for one and all, as this one. It demands nothing but faith without caring in what. This alone would be certain to bring to her every honest person in the whole world; furthermore, her Tables of the Law, starting from the Sixth Commandment (our fifth), are broken, and therefore it will also enjoy the patronage of rogues, lechers and adulterers. Also the pillar which rises between the chamber-maid and the bride, slightly towards the pulpit, is not quite of the order used in the First Church, and the pulpit itself completely resembles an ancient Chair of Philosophy, which is really what every pulpit should be. A couple of suns, with or without tonsure, one above for the pastor, and another for the congregation, could easily be painted upon it, as here, without making any difference in the matter. On the back of the pulpit one sees a dark circle which is much too clear to be just accidental. It seems to be something blotted out; a stain on a curtain which apart from its being of one piece with the rest of the cleanliness in the church may be a symbol of how much light is coming from there. I do not know... .

Taking all in all, one can well see that the physical aspect of this good Church of St Mary is not in a very good state, wherefore they have tried today to deck out the old lady, in honour of the occasion, with all kinds of foliage and green branches. Yes, it even looks to me as if that whole pillar were nothing but a crutch which they have given her today, for the sake of her noble customers, so that she might hold herself erect during the wedding ceremony at least. Thus, old, decked out and pro nunc renovated, Notre Dame, the church, reminds one somehow of Notre Dame, the bride. Yes, I almost think that part of the decoration here appertains to both ladies simultaneously. Our readers will notice that the boughs are not specially remarkable for their flowers, though they are usually very generous with these in England on such occasions, and in general on all occasions. There is merely the greenery with which the year adorns itself even while growing old, winter-green. Out of politeness it is also called evergreen, just as black clothes are called best clothes. Nevergreen and mourning coats would be more appropriate. What about thy fees, though, good Amen-chimer, if the piece of wintergreen that stands before thee knew the meaning of thy branches!

But how do we know that this is the Church of Mary-le-Bone? It is inscribed up there on the gallery: 'This church of St Mary-le-Bone was beautified in the year 1725. Tho. Sice et Tho. Horn Churchwardens. Here thus are the names not only of the church but also of the church- wardens who in the year 1725 so intensely beautified it that in the year 1735 it looked as it did. Nichols makes a point of remarking that these are not fictitious names, but they really are the names of the churchwardens of that year. A parochial inspection could not have done more. The church was in fact demolished and a new one erected into which this barn here could be fitted, even more comfortably than the one at Loretto, in its casing. The old church really was as small as this, and thus indeed very small, not more than the width of three crinolines; also the pews seem more in proportion with the church than with the human body. In the double-bed on the left-hand side, people could not possibly have been awake, certainly not standing. Even Trump, who stands here next to his little winter-green, reaches up to the key-hole. That it was indeed a pew, however, and not perhaps a relic or a holy wardrobe, is proved by the inscription. We give that here to save our readers the trouble of deciphering it for themselves. It is remarkable for the 'spelink' and diction.

THESE: PEWES: UNSCRU'D: AND: TAN: INSUNDER: IN: STONE: THERS: GRAVEN: WHAT: IS: UNDER: TO: WIT: A: VALT: FOR: BURIAL: THERE: IS: WHICH: EDWARD: FORSET: MADE: FOR: HIM: AND: HIS.

Thus it is a private church pew and not a wardrobe. However, since there is a burial vault beneath, the matter is to some extent explained. Perhaps the pew is half below ground and level with the ancestors, and would thus as temporal sleeping accommodation provide communication with the eternal through the memento mori or as a reminder of the Resurrection. Mr Gilpin has gone sadly astray as an art critic in this picture. This often happens to critics in practice. 'The perspective,' he says, 'deserves praise, only the church appears to be too small, and the wooden pillar which serves no special purpose divides the picture in a rather unsuitable way.' Mr Gilpin, usually so subtle, has not taken into consideration that the Creed and the Tables of the Law on the wall there and the face of Rakewell's sweetheart have been still more unhappily divided. Had he enquired from the churchwardens, he could perhaps have discovered the uses of the pillar. It served as a prop for the church and in addition was quite indispensable for people who have a propensity for putting the revenues of the church into their own pocket. The whole thing is drawn from life and with a purpose which, if Hogarth really had the intention of expressing ideas thereby, would conform only with a debasing and not an elevation of the subject (235-245).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 5: Bride

Shesgreen

Unreclaimed to bourgeois life by Sarah Young and determined to pursue his career as a gentleman, the rake repairs his fortune by a cynical alliance with an aged, ugly partner who trades her wealth for sexual fulfillment and class advancement.

The wife, an overdressed, one-eyed, hunchbacked creature, leers and seems to wink at the clergyman, a figure much more her match in age and looks. The small crucifix on her breast and the halo-like “IHS” above her head cast her satirically as a saint (32).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 5: Bride

Ireland

we here see this depraved lost character hypocritically violating every natural feeling of the soul to recruit his exhausted finances, and marrying an old and withered Sibyl, at the sight of whom nature must recoil.

Her charms are heightened by the affectation of an amorous leer, which she directs to her youthful husband, in grateful return for a similar compliment which she supposed paid to herself. This gives her face much meaning but meaning of such a sort, that an observer being asked, “How dreadful must be this creature’s hatred?” would naturally reply. “How hateful must be her love!” (140)

A glory over the bride’s head is whimsical (142).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 5: Bride

Dobson

Some temporary assistance [for his arrest for debt in Plate IV was] rendered to him by the unfortunate girl whom he discarded in Plate I; but it is only temporary, for in the plate that follows he is repairing his fortunes by an alliance in old Mary-le-bone Church, then much used for private marriages, with an elderly heiress. The bride is one-eyed, and tremulously exultant; the bridegroom, indifferent, and already absorbed by the good-looking lady’s maid (42).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 5: Bride

Quennell

At length, a moment arrives when the Rake must marry; and this he does, choosing as his bride a rich, elderly, one-eyed spinster, to whom he is united in Marylebone Old Church, a tumbledown edifice then almost in the open country, and because of the remoteness of its situation much favored for hasty or secret weddings (132).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 5: Bride

Lichtenberg

That the bride does not, and cannot hope to, find any fortune has been excellently expressed by Hogarth. But how does he show that the bride- groom did not find beauty? For poetic justice to his hero requires this at least. Come, dear reader, and look at the friendly angel who stands beside him; that is what he has found. Now do you complain of the lack of poetic justice? On the contrary, I am afraid your verdict may be: Summum jus, summa injuria. There will hardly be a pair of hungry eyes in the world, even if they were specially trained to look for precious metals, that would not recoil at the sight of that little treasure, just as another pair of eyes on the first Plate flinched before another little treasure box— Ugh! Only guineas! It is too bad. But we shall see.

It has been observed long ago that it would be much better for ladies' adornments, and consequently for the ladies themselves, if they were more intent upon the subordination between their two great dressmakers, Nature and Art. But as a rule the latter, an amiable, ingratiating witch, is mistress of the house, and thus it is not surprising if the other completely withdraws sometimes, or else, when the former has finished with her flimsy work, uncovers with one jerk, but with infinite subtlety, a little spot of contrast, and thereby puts all art to shame. Thus, for instance, the head of the bride would not have been at all bad if she had only let Nature have her way. For though chance has deprived the poor creature of an eye, that in itself would not have rendered her ugly, but now comes die above-mentioned busybody and to improve matters she puts that omission, by means of a few stuck-on beauty-spots, so obviously among the errata, that nobody can fail to detect it at once. I challenge the world to tell me whether the pair of natural eyes that stand there in the face of the bride like an iambus (u -) is one whit more disagreeable than the sly, artificial spondeus (- -) in the face of the bridegroom? Apart from this, one might apply to the remaining eye what the English Aristophanes says about the eye of Lady Pentweazle's great-aunt: 'Although it stands alone, it is a genuine piercer, and procures her three husbands for one.' Also, as it seems to me. Art could have been better advised to leave her mouth as it was, without the quite purposeless u-shape. This is the sign for short syllables. All right; but a mouth cut to the pattern of the sign for short syllables is for that matter not yet a short cut. The whole symbol is no use anyway. Had the first poets understood geometry they, would surely not have denoted the long by the natural symbol for the short, nor the short by the symbol for the curved and the roundabout.

Although, in some respects. Art has been somewhat niggardly in its dealings with that bride, in others it has not treated her quite so badly, and this deserves honourable mention. Thus, for instance, the circum- stance that the lady is almost two feet shorter than her bridegroom, and only four fingers taller than her chambermaid who kneels behind her, is a natural deficiency which has as far as possible been counteracted by Art. It is only a pity that the ceremonial height with which it has endowed the lady is not designed for the still, stuffy air of a village church, but rather for a Zephyr in the Park, or the whirlwind of a waltz at the Ball. We observe that she has the peacock adornment of her lovelier part, I mean the feathered tail of her head-dress, swept backwards. In a storm or a whirl- wind she would float along like a Juno. But though she may add to her stature, thereby, this is neither the time nor the place for it. The words of thunder "And he shall be thy master' could fold up all the splendour of the world, as could rain the loveliest peacock's tail. Some people have found fault with Art for having left the bride's ear so unbecomingly uncovered. Now I cannot see anything in this. I rather find fault with Rakewell's peruquier for having so completely covered up his. At a wedding ceremony ears are more needful than eyes; and then I find the little touch of vanity in a half-blind person, especially one blessed with a somewhat suspect physiognomy, in wanting to show that she has at least both her ears, very natural and human.

But now we come to a major question: is the bride still a virgin?—or more properly, is the bride there a widow or not? A matter which nobody else in the world would trouble about is often of paramount importance to an author, and that is the case with us here. Were she neither virgin nor widow, I would at least have to ask the reader to cut out a line from the beginning of this Chapter where it was said that Rakewell was entering the sign of Virgo. But it can quietly stay where it is. For the benefit of the doubters in such a delicate question a miracle has come to pass, so beautiful that if it is genuine, which nobody could well doubt since it is so beautiful, Madame Rakewell's name would deserve to be honoured in red letters. On the pulpit behind her are the well-known arms of the Jesuits, a sun with the letters I.H.S., which have this in common with the Jesuits themselves, that one can make out of them what one will, provided it is something good. That sign stands here, in full conformity with its meaning, just above the head of injured innocence and thus becomes the Virgin's crown. Yet, what renders this miracle wonderful even as a miracle is that the connection is evident only from the side where we, the doubters and sneerers unfortunately, stand! Just as ghosts are known to appear, in the largest gatherings, only to those whom to convert or to frighten they have left their graves. To believe and hold one's peace is to be wise (236-238).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 5: Commandments

Paulson observes that Hogarth also implicates the church for allowing such unions as its "dilapidated condition . . . repeats the physical and moral condition of the pair," also noting a crack in the plaque of the 10 Commandments, carefully observing that this break stops short of the tenth-Thou Shalt Not Covet Thy Neighbor's Wife- indicating that sexual crimes again foremost here (Graphic 166).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 5: Commandments

Paulson, Hogarth's Graphic Works

The Creed is torn (or rotted) so that only the beginning, "I believe, is legible; the tablet of the Commandments from VI through X is cracked--significantly it is the second tablet, which deals with "Duties to our Neighbors." The crack stops short, however, of the Tenth Commandment, which includes "Thou shalt not covet thy neighbor's wife" (167).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 5: Commandments

Ireland

The Commandments are broken: a crack runs near the tenth which says, “Thou shalt not covet thy neighbour’s wife;” a prohibition in the present case hardly necessary. The Creed is destroyed by the damps of the church; and so little attention has been paid to the poor’s box, that—it is covered with a cobweb!!! These three high-wrought strokes of satirical humour were perhaps never equaled by an exertion of the pencil; excelled they cannot be (142).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 5: Commandments

Lichtenberg

Behind the clergy of the establishment are the Tables of the Law, one of which has a strong crack running through the ninth Commandment (our eighth): 'Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbour.' For the Anglican Church makes two Commandments out of our second, and by way of compensation, one out of our ninth and tenth. From that apparently negligible, theoretical alteration, however, arises a great difference in practice. Every crime in pto. sexti, for which, in the greater part of Germany (where it refers to the relations between parents and children), nobody gives a damn, is in England inevitably punished by hanging, for there it refers to murder. By way of compensation, however, we in Germany, provided nothing untoward happens, hang the trespasser against the seventh (stealing), whereas in England the thief can marry his accomplice (in adultery) and go where he likes (242-243).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 5: Dogs

Despite the seriousness of the overall theme, the plate is heavy on humor. The two dogs, obviously meant to symbolize the newlyweds, highlight the silliness of the pair’s imminent lovemaking. The male dog has been consistently identified as a likeness of Hogarth’s own favorite canine.

A Rake's Progress: Plate 5: Dogs

Shesgreen

A large, aggressive dog and a smaller one-eyed bitch mirror the alliance taking place at the right (32).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 5: Dogs

Paulson, Hogarth's Graphic Works

the two dogs courting offer a parallel to the human situation; like the old woman, the courted dog has only one eye. (The male dog is supposed to be Hogarth's Trump: Gen. Works, 2, 122.) (166).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 5: Dogs

Ireland

A dog (“Trump,” Mr. Hogarth’s favourite dog, which has introduced in several of his prints.) paying his addresses to a one-eyed quadruped of his own species, is a happy parody of the unnatural union going on in the church (141).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 5: Dogs

Lichtenberg

On the left-hand side, immediately behind the hassock, is a small tête-à-tête which stands to the main group in this picture in almost the same relation as the Assembly of Black Patricians on the pavement, described above, to that in White's Coffee House. Hogarth's immortal pug-dog called Trump, a lively male, is observed in secret conversation with an elderly creature of his species but of the opposite sex, which deserves our attention for the reason that it is carried on with three eyes only. If we examine the group a little more closely we cannot help arriving at some rather queer ideas, for does it not look as if the little bitch were boasting other white breast, of the little shiny bells round her neck, and of some- thing which looks very much like a small metal plate? And there is really something hanging down behind which would be more suitably paraded in the open air, or at a so-called Wedding procession in the street, than in here. All that is missing is a little bitch to occupy itself with the culotte of the amiable lady, in which case Trump would probably also squint that way, over the head of his beloved, whereby a certain similarity, which we must not proclaim too loudly, would be complete. But no! Trump is honest, and as one can see from his whole attitude, which he has not learnt from an Essex, does not ask for anything to be thrown in (241-242).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 5: Maid

The old bride’s attending maid is the object of Tom’s leer.

A Rake's Progress: Plate 5: Maid

Dobson

The bride is one-eyed, and tremulously exultant; the bridegroom, indifferent, and already absorbed by the good-looking lady’s maid (42).

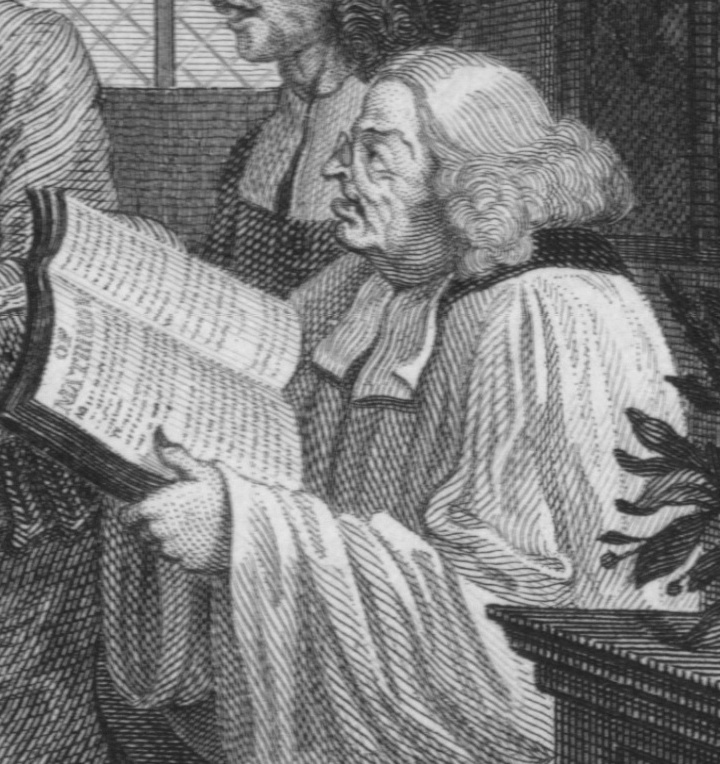

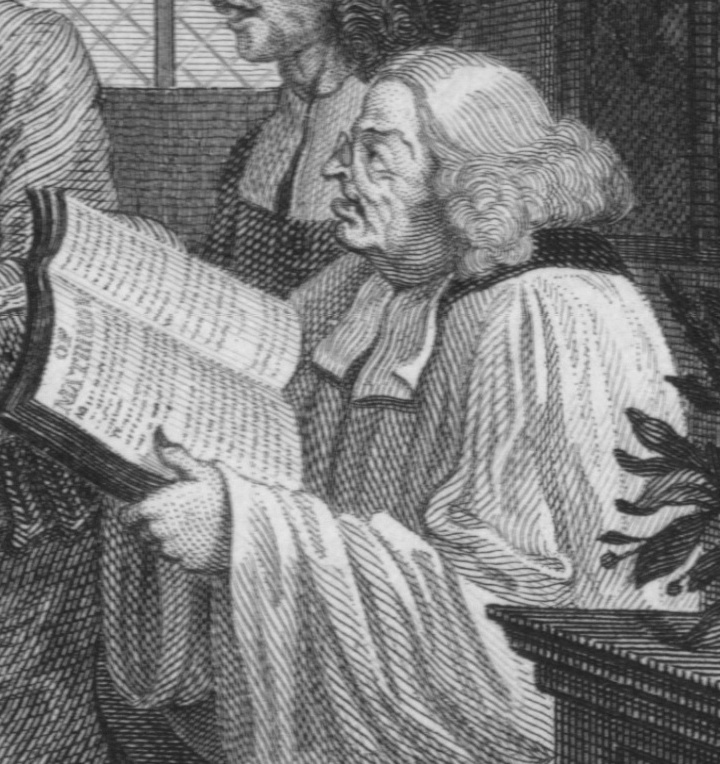

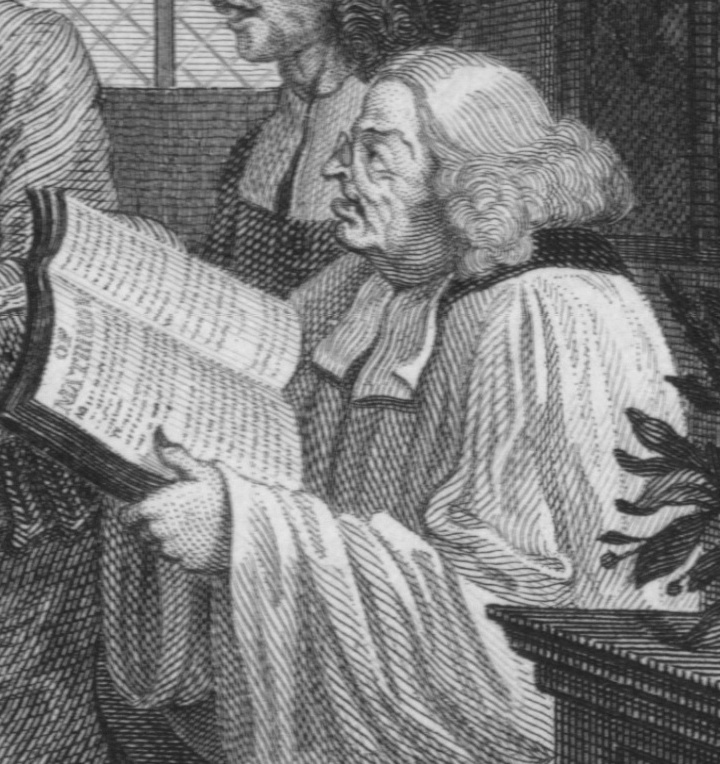

A Rake's Progress: Plate 5: Minister

A particularly hideous, clownish parson presides over the ceremony.

A Rake's Progress: Plate 5: Minister

Ireland

A parson and clerk seem made for each other: a sleepy, stupid solemnity marks every muscle of the divine, and the nasal droning of the lay brother is most happily expressed. Accompanied by her child and mother, the unfortunate victim of his seduction is here again introduced, endeavouring to enter the church and forbid the banns. The opposition made by and old pew-opener, with her bunch of keys, gave the artist a good opportunity for indulging his taste in the burlesque, and he has not neglected it (141).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 5: Minister

Lichtenberg

Before the bridal pair, like two liturgical clocks, stand the parson and the parish clerk; they are both set at 'Wedding', the former being the regulator, the latter the chimer. The English institution of parish clerk is one which will certainly disappear as soon as Herr von Kempelen has succeeded in constructing his talking machine; even now, one would think, a clock that could strike 'Amen' would not be more difficult to construct than one calling 'Cuckoo'. One can almost hear the man bleating his tedious 'Amen'. However, beneath that cold official mien one can still discover a little glimmer of mischief. I fear it is about the semi-secular feast which is here solemnized as if it were a Day of Dedication. About the Pastor, Mr Gilpin observes, quite excellently, that everybody who looks at him thinks that he has somewhere seen such a face and such a wig, but cannot for the moment say where. It would be impossible to praise our artist more highly in so few words. Eyebrows, eye, mouth (sit venia verbo), nay everything down to the very thumbs are cut as if out of one piece. The boy in front of the bride who is occupied in pushing a hassock before her, since the kneeling down is imminent, belongs, as we can see from his little collar, to the Charity School of the parish. His miserable clothes demonstrate that the Director so manages matters that the children do not forget how to beg. One never knows whether they may not need to again. Jacket and stockings are torn, and from the shoes peep not only the feet of the stockings, but the toes themselves. Since, as we shall hear soon, this Church, and consequently the parish, are very clearly indicated, Hogarth must have known whom he had before him when he dealt such blows (239-240).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 5: Poor Box

Lichtenberg

But how do we know that this is the Church of Mary-le-Bone? It is inscribed up there on the gallery: 'This church of St Mary-le-Bone was beautified in the year 1725. Tho. Sice et Tho. Horn Churchwardens. Here thus are the names not only of the church but also of the church- wardens who in the year 1725 so intensely beautified it that in the year 1735 it looked as it did (241).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 5: Sarah and Mom

The Rake's actions have led him to an unnatural and financially-motivated sham marriage with an aged woman who, as Shesgreen observes, "trades her wealth for sexual fulfillment" (32). This occurs while Sarah and his real, though illegitimate, child attempt to stop the ceremony. The assured barrenness of his current union and the bastard status of his actual child show the breakdown of the family resulting from random sexual misbehavior.

Sarah is also pictured in Plate 1, where Tom has rejected her,;in Plate 4, where pays an arresting officer on his behalf; in Plate 7 where she faints at his incarceration in a debtors’ prison; and in Plate 8 where she attends him in Bedlam.

A Rake's Progress: Plate 5: Sarah and Mom

Shesgreen

In the background a churchwarden battles with Sarah Young and her clawing mother, who have come with the rake’s child to prevent the marriage (32).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 5: Sarah and Mom

Paulson, Hogarth's Graphic Works

In the background the pew opener waves her keys in an attempt to keep out Sarah Young with her baby and her mother, who have come to forbid the banns (166).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 5: Sarah and Mom

Quennell

Sarah Young does her best to intervene; but she is beaten back by a pew-opener (132).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 5: Sarah and Mom

Lichtenberg

My readers will have noticed that a violent storm is really raging in the background here. The trouble is briefly this. Sarah Young has saved her abominable seducer by sacrificing her little all. He promised her marriage for the second time and—here for the second time betrays her. She appears here with the child, this time in her arms, to protest against the union of her seducer with another woman. Probably she did all this on the advice other mother who, to judge from her physiognomy, holds somewhat different views about the ways of Heaven than does her good- natured daughter. The latter surrenders to its will in the hope of a better future; the former, on the other hand, is in favour of at least trying whether, by the use of the fists which Heaven has granted her, something might not be done already upon earth. She thus arrives here with her daughter at the harbour, but as she is about to enter, and is already making headway, they are met by such terrific breakers that the daughter is immediately driven out again. The mother, though she tries to battle with the waves, and throws out a five-pronged anchor, finds that such measures cannot help much here and, as we shall see, they have in fact not helped at all. The Sexton's wife, or some other aged pew-opener, well versed in the law of the Church, who may be apprehensive of the Power of the Keys and of the loss of the stole-fees, seizes a bundle of Church keys and, entirely contrary to reason and equity (and specially the compelle intrare), starts hitting out against the two protesting women. The daughter, gentle and yielding and more concerned for her child and her mother than for her own rights, compromisingly withdraws. The mother, on the other hand, takes up arms and defends herself desperately to the last with large and small, though always natural, guns. To understand this classification of natural arms, one must know that in England when men quarrel, they carefully draw in their nails and endeavour with clenched fist, by weight and swing alone, to fell their adversary. But the women on such occasions leave their nails out and try not so much to down the enemy as to bleed him with a ten-bladed scarifier. Madame Young, however, fights here like an Amazon, combining the scarifier with the cudgel, and yet victory is not for her; she has the clergy against her! If from that storm one turns one's thoughts again to Rakewell's face, it almost seems as if he heard and not a little feared its roaring. Apart from him nobody in the whole Assembly seems to pay much attention to it, except perhaps the sole 'dearly beloved brother', the pious listener, up in the Gallery (240-241).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 5: Rake

The Rake's actions have led him to an unnatural and financially-motivated sham marriage with an aged woman. Rakewell takes the opportunity to divert his attention to the maid attending his bride. Even on his wedding day, a libertine must maintain his values.

A Rake's Progress: Plate 5: Rake

Shesgreen

Unreclaimed to bourgeois life by Sarah Young and determined to pursue his career as a gentleman, the rake repairs his fortune by a cynical alliance with an aged, ugly partner who trades her wealth for sexual fulfillment and class advancement.

The rake, a stately, attractive figure, is in the act of prostituting himself in much the same way as the harlot did in Plate II. As he slips the ring on his wife’s finger, he glances calculatingly at her young maid (32).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 5: Rake

Uglow

Tom buys his way out with a furtive wedding to a rich, leering old woman (254).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 5: Rake

Ireland

we here see this depraved lost character hypocritically violating every natural feeling of the soul to recruit his exhausted finances, and marrying an old and withered Sibyl, at the sight of whom nature must recoil (140).

In his demeanour we discover an attempt to appear at the altar with becoming decorum: but internal perturbation darts through assumed tranquility for though he is plighting his troth to the old woman, his eyes are fixed on the young girl who kneels behind her (141).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 5: Rake

Dobson

Some temporary assistance [for his arrest for debt in Plate IV was] rendered to him by the unfortunate girl whom he discarded in Plate I; but it is only temporary, for in the plate that follows he is repairing his fortunes by an alliance in old Mary-le-bone Church, then much used for private marriages, with an elderly heiress. The bride is one-eyed, and tremulously exultant; the bridegroom, indifferent, and already absorbed by the good-looking lady’s maid (42).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 5: Rake

Quennell

At length, a moment arrives when the Rake must marry; and this he does, choosing as his bride a rich, elderly, one-eyed spinster, to whom he is united in Marylebone Old Church, a tumbledown edifice then almost in the open country, and because of the remoteness of its situation much favored for hasty or secret weddings (132).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 5: Rake

Lichtenberg

He appears to have made a fortunate escape from the jaws of the British Lion of Justice, and here he is entering the sign of the Virgin (Virgo). The sign itself is depicted, but requires some explanation. Rakewell's paternal fortune has gone, and the whole conglomeration of boxes and cupboards and corners which we saw on the first Plate may still contain many a little trifle for pussy, but alas! no longer anything for him. To fill that terrible void he has opened up in the East End a small bartering business with his manly figure, and this has prospered so delightfully that everything filled up once more. To understand that business thoroughly, one should know that in the orient of London live the true money-planters who concentrate specially upon cultivating its seeds; in the Occident, on the other hand, they are more occupied with the enjoyment of the plant itself, and have so little thought for the future that families often find themselves compelled to obtain fresh seeds from the orient, on stringent terms. It is just such a bargain whose contract is being concluded here; only the conditions are not too strict; he merely has to marry, and the wedding is now being solemnized. Bride and bridegroom have found what they each sought: she a handsome young man, he a rich wife; what more does one want? That neither of them found what they did not seek is nobody's business, least of all a motive for rejoicing in another's misfortune, as I have sometimes found it among people to whom I have shown that wedding scene. But they were quite wrong in this. A sensible man will express his enjoyment of other people's misfortune only if he perceives that they have been deceived in their hopes; but where is anything of that kind here? She did not look for riches and did not find any. And he? He did not look for beauty, and so he found none. On the contrary, he found debts to Nature into the bargain. This is the theme (235-236).

Rakewell's figure is not utterly devoid of grace. One sees that Essex can achieve something when he tries, so can the proposition: 'Quarter of a century younger and two feet taller.' In his eye gleams a sense of superiority coupled with an easy contempt and dissimulation, with a touch of the lover's roguery. Without that touch we could have spoken of Jesuit signs here too. The ears we cannot see and the eyes—only just! But they themselves are keenly focused. Their glance passes right through the bride's halo, without disturbing it, on to a little item from the bride's Inventory, the chamber-maid, who, compounded with the rest of the Capital, has evidently contributed to the completion of the bargain (238-239).

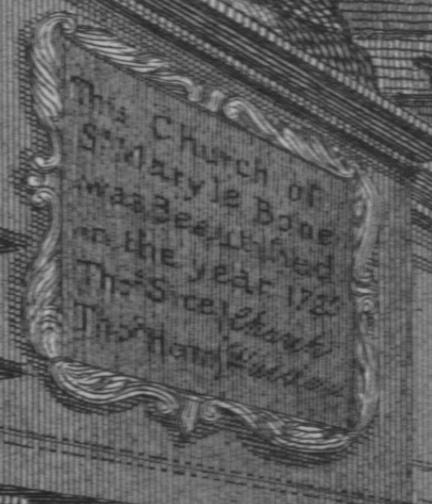

A Rake's Progress: Plate 5: Wall Text

Shesgreen

The scene of this mock religious ceremony is the decayed church of St. Mary-le-Bone, famous for clandestine marriages (the gallery holds a plaque reading “This Church of St. Mary le Bone was Beautified in the year 1725, Tho Sice Tho Horn Church Wardens”) (32).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 5: Wall Text

Paulson, Hogarth's Graphic Works

It is Marylebone Old Church, which was almost out in the country and therefore popular as a place for secret or hasty weddings. The inscription on the balcony announces: "This Church of St Mary le Bone was beautifyed in the year 1725 Tho Sice Tho Horn Church Wardens." ]. J. Ireland (I, 48 n., following Biog. Anecd., 1785, p. 217 n.) notes that Sice and Horn "were really churchwardens in the year 1725, when the repairs were made. This print came out only ten years afterwards and the present state of the building seems to intimate, that Messieurs Sice and Horn had cheated the parish, when they officially superintended the affairs of their church." (167).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 5: Wall Text

Uglow

For his the scene of Tom’s marriage Hogarth drew the dilapidated walls of Marylebone Old Church. The setting was symbolic: the Creed ruined by damp, the Ninth Commandment cracked, the poor box covered by a cobweb. But the inscription on the pews, announcing that the Forset family vault lies beneath, was genuine enough; so was the monument to the Taylors, seen under the window. And so was the inscription on the wall announcing the church “was beautifyed in the year 1725, Tho, Sice, Tho. Horn Church Wardens”. These men really were the churchwardens when the “repairs” were done, and Hogarth need show no more to suggest they had cheated the parish. The crumbling church was pulled down six years later (299) .

A Rake's Progress: Plate 5: Wall Text

Quennell

At length, a moment arrives when the Rake must marry; and this he does, choosing as his bride a rich, elderly, one-eyed spinster, to whom he is united in Marylebone Old Church, a tumbledown edifice then almost in the open country, and because of the remoteness of its situation much favored for hasty or secret weddings (132).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 5: Wall Text

Lichtenberg

But how do we know that this is the Church of Mary-le-Bone? It is inscribed up there on the gallery: 'This church of St Mary-le-Bone was beautified in the year 1725. Tho. Sice et Tho. Horn Churchwardens. Here thus are the names not only of the church but also of the church- wardens who in the year 1725 so intensely beautified it that in the year 1735 it looked as it did. Nichols makes a point of remarking that these are not fictitious names, but they really are the names of the churchwardens of that year. A parochial inspection could not have done more. The church was in fact demolished and a new one erected into which this barn here could be fitted, even more comfortably than the one at Loretto, in its casing. The old church really was as small as this, and thus indeed very small, not more than the width of three crinolines; also the pews seem more in proportion with the church than with the human body (244).

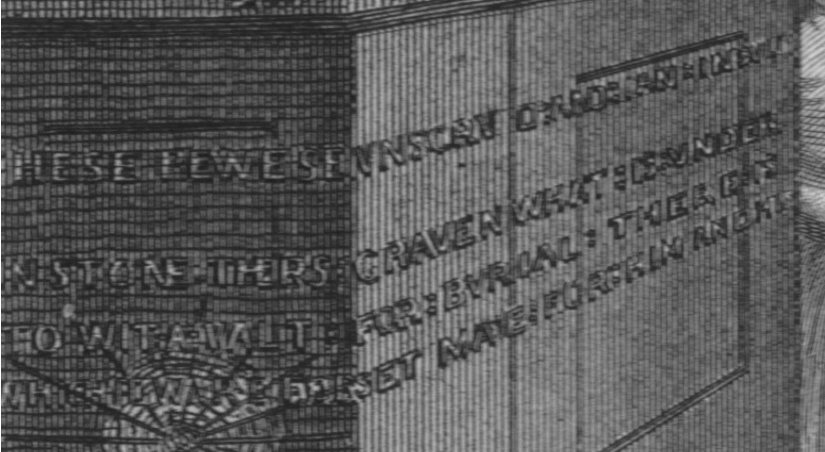

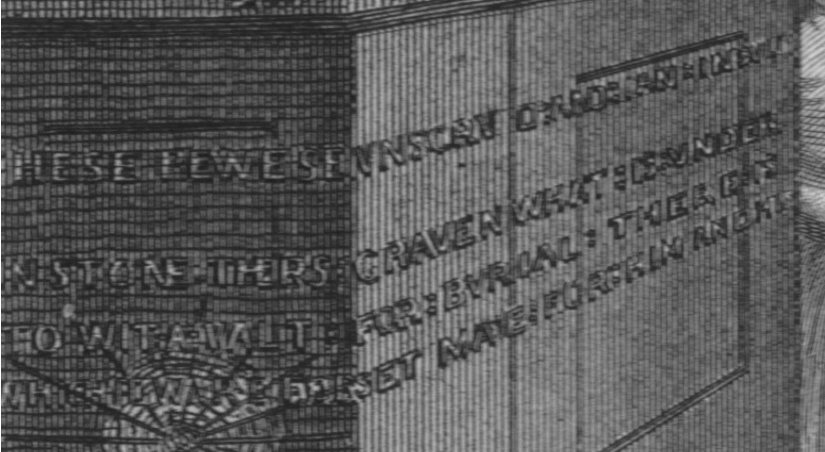

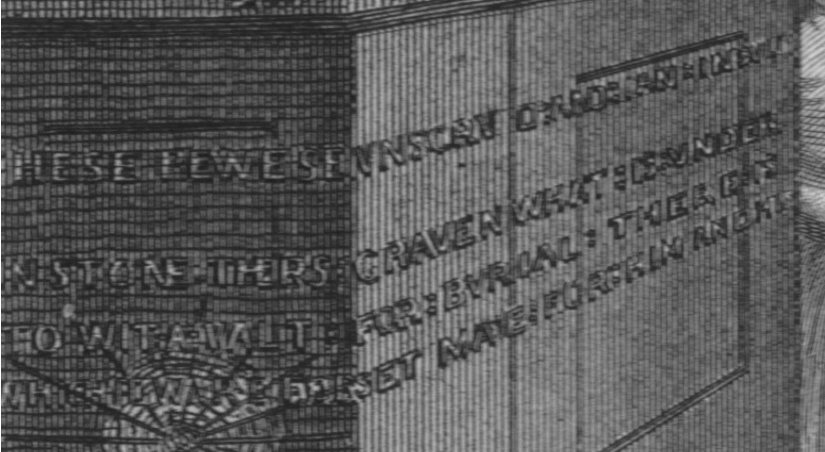

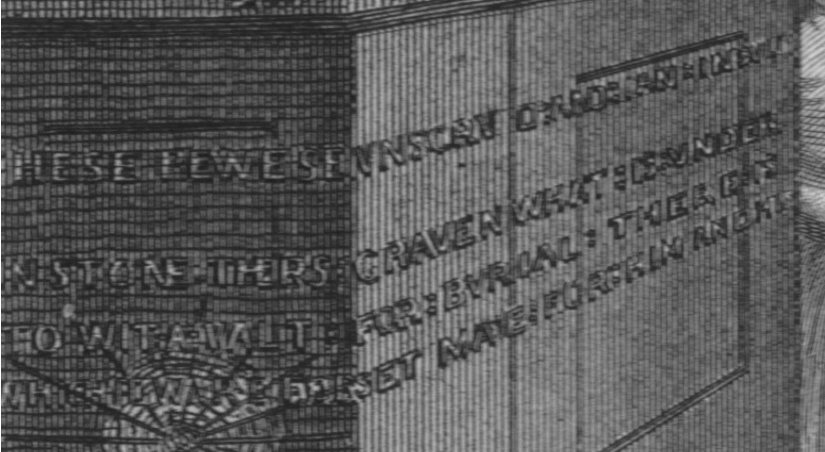

A Rake's Progress: Plate 5: Pew

The inscribed pew shows the extent to which the church is for sale. It reads: These: pewes vnscrvd: and: tan: in. svnde[r]/ In. stone: thers: graven: what: is: vnder/ To wit: a: valt: for: bvrial: there: is/ Which: Edward: Forset: made: for: him: and: his"

A Rake's Progress: Plate 5: Pew

Shesgreen

The pew at the left, like clergyman and church, belongs to those who can buy it. The inscription reads: “These: pewes vnscrvd: and: tan: in. svnde[r]/ In. stone: thers: graven: what: is: vnder/ To wit: a: valt: for: bvrial: there: is/ Which: Edward: Forset: made: for: him: and: his (32).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 5: Pew

Paulson, Hogarth's Graphic Works

The inscription on the pew at left reads: "THESE: PEWES VNSCRVD: AND: TANE: IN. SVNDE[r] / IN. STONE: THERS: GRAVEN: WHAT: IS: VNDER / TO: WIT: A: VALT: FOR: BVRIAL: THERE: IS / WHICH: EDWARD: FORSET: MADE: FOR: HIM: AND: HIS." As Nichols and Steevens explain (Gen. Works, 2,123): Part of these words, in raised letters, at present form a pannel in the wainscot at the end of the right-hand gallery, as the church is entered from the street.--No heir of the Forset family appearing, their vault has been claimed and used by his Grace the Duke of Portland, as lord of the manor. The mural monument of the Taylors, composed of lead gilt over, is likewise preserved. It is seen, in Hogarth's Print, just under the window. The Bishop of the diocese, when the new church was built, gave orders that all the ancient tablets should be placed, as nearly as possible, in their former situations. (166-167).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 5: Pew

Ireland

On one of the pew-doors is the following curious specimen of churchyard poetry and mortuary orthography:-- THESE: PEWES; VNSCRUD; AND TANE; SVNDER IN: STONE: THERS: GRAUEN: WHAT: IS: VNDER TO: WIT: A VALT: FOR: BURIAL: THERE: IS WHICH: EDWARD: FOREST: MADE: FOR: HIM: AND: HIS (It appears from an examination of the registers, etc. that Thos. Sice and Thos. Horn were really churchwardens in the year 1725, when the repairs were made. This print came out only ten years afterwards; and the present state of the building seems to intimate that Messieurs Sice and Horn had cheated the parish, when they officially superintended the affairs of their church (141).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 5: Pew

Lichtenberg

That it was indeed a pew, however, and not perhaps a relic or a holy wardrobe, is proved by the inscription. We give that here to save our readers the trouble of deciphering it for themselves. It is remarkable for the 'spelink' and diction. THESE: PEWES: UNSCRU'D: AND: TAN: INSUNDER: IN: STONE: THERS: GRAVEN: WHAT: IS: UNDER: TO: WIT: A: VALT: FOR: BURIAL: THERE: IS: WHICH: EDWARD: FORSET: MADE: FOR: HIM: AND: HIS. Thus it is a private church pew and not a wardrobe. However, since there is a burial vault beneath, the matter is to some extent explained. Perhaps the pew is half below ground and level with the ancestors, and would thus as temporal sleeping accommodation provide communication with the eternal through the memento mori or as a reminder of the Resurrection. Mr Gilpin has gone sadly astray as an art critic in this picture. This often happens to critics in practice. 'The perspective,' he says, 'deserves praise, only the church appears to be too small, and the wooden pillar which serves no special purpose divides the picture in a rather unsuitable way.' Mr Gilpin, usually so subtle, has not taken into consideration that the Creed and the Tables of the Law on the wall there and the face of Rakewell's sweetheart have been still more unhappily divided. Had he enquired from the churchwardens, he could perhaps have discovered the uses of the pillar. It served as a prop for the church and in addition was quite indispensable for people who have a propensity for putting the revenues of the church into their own pocket. The whole thing is drawn from life and with a purpose which, if Hogarth really had the intention of expressing ideas thereby, would conform only with a debasing and not an elevation of the subject (243-245).