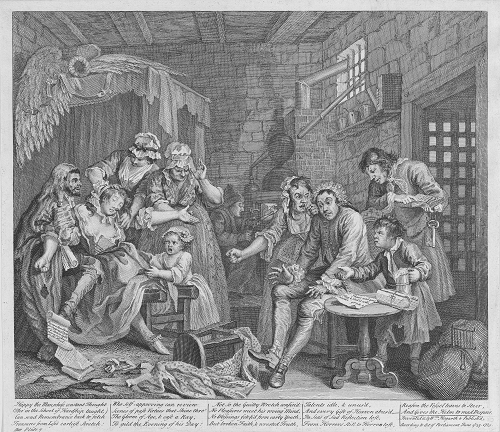

A Rake's Progress: Plate 7

1735

12 3/8” X 15 1/16” (H X W)

Etched and Engraved by Hogarth after his painting.

View the full resolution plate here.

Hogarth allows his tale to take a melodramatic turn in this seventh plate. Tom no longer appears as the licentious gambling rake. Instead, he is in debtors’ prison; a rejection from a publisher equates him with the other misunderstood and failed dreamers. His cellmates are an alchemist vainly trying to produce gold (perhaps symbolizing Tom’s own futile efforts to make money with his writing) and a projector whose imprisonment for debt is ironically underscored by his lofty plans to solve the financial problems of the nation. Hogarth is suggesting that, to solve England’s problems, one must concentrate on reforming the individual.

Tom is indeed at the end of his financial rope, as he can pay neither the turnkey nor the boy bringing him ale. His wife rightfully admonishes his wastefulness; his frustrated posture reveals his realization that he has run out of chances.

Sarah is here; she has fainted with the sudden realization that Tom will never make a proper husband or father. Their daughter, with a face like a small adult, pragmatically attempts to rouse her mother from her spell.

The dreams of all involved are as deadly as Icarus’s attempt to fly too close to the sun. A pair of wings in the corner of the plate make this mythological link explicit.

A Rake's Progress: Plate 7

Shesgreen, Sean. Engravings by Hogarth. (1973)

The promise of Plate IV is here fulfilled and the rake, like the harlot before him, is jailed (for debt). The scene is the crude stone interior of the Fleet, a debtors’ prison. The rake, slumped listlessly forward, his face filled with despair and anomie, besieged on all sides, gestures helplessly with his hands and feet. His last desperate attempt to earn money by writing a play has failed; beside him lies a curt rejection: “Sr. I have read your Play & find it will not doe yrs. J.R. .h..” The misspelled “doe” seems to be a hit at the theater manager and pantomimist John Rich. Rakewell is now so destitute that he cannot give the turnkey the “garnish money” or pay the perturbed youth for a mug of beer. While his shrewish wife assaults him, Sarah Young faints in compassion at his plight. A companion shoves her head toward a bottle of smelling salts; another slaps her hand, while her daughter seems to rebuke the mother for her conduct.

The rake’s two cellmates forecast his impending fate; both are, to some degree, mad. The unkempt fellow with the ragged wig and heavy beard who supports Sarah is a projector though he cannot pay his own debts he has just invented a “Scheme for paying ye Debts of ye Nation.” The fellow in the corner with the nightcap (who has been there a long time if we are to judge by his elaborate still and chimney) is a mad alchemist. He is too absorbed in his furnace project (probably attempting to turn metal into gold) to notice what transpires around him. His telescope sticks out through the prison bars; three mixing pots stand beside his meager library; a paper inscribed “Philosophical” protrudes from one volume. Above his canopy rests a pair of wings. Like the rake, his plans to soar beyond his natural realm have brought him only imprisonment and insanity (34).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 7

Paulson, Ronald. Hogarth’s Graphic Works. (1965)

CAPTION:

Happy the Man, whose constant Thought

(Tho' in the School of Hardship taught,)

Can send Remembrance back to fetch

Treasures from Life's earliest Stretch:

Who Self-approving can review

Scenes of past Virtues that Shine thro'

The Gloom of Age, & cast a Ray,

To gild the Evening of his Day!

Not so the Guilty Wretch confin'd:

No Pleasures meet his roving Mind,

No Blessings fetch'd from early Youth,

But broken Faith, & wrested Truth,

Talents idle, & unus'd,

And every Gift of Heaven abus'd,—

In Seas of sad Reflection lost,

From Horrors still to Horrors tost,

Reason the Vessel leaves to Steer,

And Gives the Helm to mad Despair.

Having lost all his wife's money in the gambling house, Rakewell is confined in a debtors' prison (the Fleet Prison). His old one-eyed wife (who seems to have lost some weight) harangues him; Sarah Young, accompanied by their child, has arrived and fallen into convulsions—perhaps as a result of the latest bad news. In those days every gentleman wrote a play, and so Rakewell has thus attempted to recoup his losses; his manuscript has just been returned to him ("Act 4" is legible in the roll of manuscript) with a letter: "Sr I have read your Play & find it will not doe y8 J. R. .h" (John Rich, manager of the Covent Garden Theatre). This latest blow may account for Sarah's convulsions as well as Rakewell's expression. Finally, the turnkey demands "Garnish money" (as his ledger shows), and a boy demands money for a pot of beer he has brought him.

With all of this closing in on him, the possible ways out of his situation make up the rest of the print: the pair of wings on top of the four-poster, the alchemist's forge at the rear, and the alchemist busy trying to make gold. On the shelf just below the window are crucibles numbered from 1 to 3 and two books, a paper marked "Philosophical" stuck in one of them. A telescope protrudes through the bars of the window. The unkempt man who is helping Sarah drops a scroll on which is written "Being a New Scheme for paying ye Debts of ye Nation by T: L: now a prisoner in the Fleet," and another marked "... Debts" (a memory of the South Sea Company). Plate 8 shows Rakewell's way out (168-169).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 7

Ireland, John and John Nichols. Hogarth’s Works. (1883)

It is pithily and profitably observed by Mr. Hugh Latimer, or some other venerable writer of his day, that “the direct path from a gaming-house is unto a prisonne, for the menne who doe neeste themselves in these pestiferous hauntes, being either fooles nor cheates, be punished: if fooles, but their own undoing; if cheates, by the biting lash of the beadle, and the durance of their vile bodies.”

In the plate before us, this remark is verified. Our improvident spendthrift is now lodged in that dreary receptacle of human misery—a prison. His countenance exhibits a picture of despair; the forlorn state of his mind is displayed in every limb, and his exhausted finances by the turnkey’s demand of prison fees not being answered, and the boy refusing to leave a tankard of porter unless he is paid for it.

We learn by a letter on the table, that a play which he sent for the manager’s inspection “will not doe” (I am afraid that Mr. William Hogarth was ignorant of spelling, for his warmest admirers to contest the point any longer); and we see by the enraged countenance of his wife, that she is violently reproaching him for having deceived and ruined her. To crown this catalogue of human tortures, the poor girl whom he deserted is come with her child,--perhaps to comfort him, to alleviate his sorrows, to soothe his sufferings; but the agonizing view is too much for agitated frame; shocked at the prospect of that misery which she cannot remove, every object swims before her eyes, a film covers the sight, the blood forsakes her cheeks, her lips assume a pallid hue, and she sinks to the floor if the prison in temporary death. What a heart-rending prospect for him by whom this is occasioned! Should he in the anguish of his soul inquire. “Who is it that hath caused this?” that inward monitor, which to him must be a perpetual torment, would replay in the words that Nathan said unto David, “Thou art the man!” Such an accumulation of woe must shake reason from her throne. The thin partitions which divide judgment form distraction are thrown down, and the fine fibres of the brain are overstrained, and in the place of godlike apprehension, “Chaos and anarchy assume the sway.” That balm of a wounded mind,--the recollection of connubial love, parental joys, and all the nameless tender sympathies which calm the troubled soul,--in his blank and blotted memory find no place. Remorse and self-abhorrence rankle in his bosom! his groans, heaved from the heart, pierce the air! he is chained! rages! gnashes his teeth and tears his quivering flesh! At this dreadful crisis he sees, or seems to see,

A fiend, in evil moments ever nigh,

Death in her hand, and frenzy in her eye!

Here eye all red, and sunk! A robe she wore,

With life’s calamities embroidered o’er.

From me (she cries), pale wretch, thy comfort claim,

Born of Despair, and Suicide my name.

He attempt to take away that life which is become hateful to him; is prevented, and removed to a cell more dreadful than even a prison: “Where Misery and Madness hold their court.” But let us for a moment return to the present scene. The wretched, squalid inmate who is assisting the fainting female, bears every mark of being naturalized to the place: out of his pocket hangs a scroll, on which is inscribed, “A scheme to pay the national debt, by J.L. now a prisoner in the Fleet.” So attentive was this poor gentleman to the debts of the nation that he totally forgot his own. The cries of the child, and the good-natured attentions of the two women, heighten the interest, and realize the scene. Over the group are a large pair of wings, with which some emulator of Dedalus intended to escape from his confinement; but finding them inadequate to the execution of his project, has placed them upon the tester of his bed. They would not exalt him to the regions of the air, but they o’er-canopy him on earth. A chemist in the background, happy in his views, watching the moment of projection, is not to be disturbed from his dream by anything less than the fall of the roof or the bursting of his retort; and if his dream affords him the felicity, why should he be awakened? The bed and gridiron, those poor remnants of our miserable spendthrift’s wrecked property, are brought here as necessary in his degraded situation; on one he must try to repose his wearied frame, on the other he is to dress his scanty meal.

The grated gate, secured with tenfold bars of iron, reminds us of Milton’s “Infernal doors, that on their hinges grate’ Harsh thunder!”

The principal figure is wonderfully delineated. Every muscle is marked, every nerve is unstrung; we see into his very soul. The poor prisoner who is assisting the fainting woman is ill-drawn; the group of which she is the principal figure is unskilfully contrived: if forms a round heavy mass. The opposite group, though better, is not pleasing (148-152).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 7

Uglow, Jenny. Hogarth: A Life and a World. (1997)

When Tom himself sits helpless in the Fleet with all his money gone, he wears that same fierce inner gaze [see Plate VI], and another small boy reminds him of his drink and holds out his hands for coins.

Hogarth’s drawing always recalls the theatre; a stage gesture of rape, and actor’s broad presentation of misery and madness. But in the Fleet scene Tom’s pose is a startling physical contrast of introspective despair, in the stillness of his head and shoulders, and the jerking agitation of his restless hands and feet. Opposite him, Sarah has fainted, while their child tugs her skirt. And beside her stands a wry reminder of men like Hogarth’s own father, a puzzled, disheveled figure with a cheap wig aslant on his dark hair, his blunt, stubbly face gawping in distress; from the pocket of his dressing-gown, full of holes, a paper floats to the ground, “A New Scheme for solving the Debts of the Nation”. Once again, we are in the stage set of nightmare, the locked room of bricks and barred windows. Looking back, the bars and chains have always been there—the padlock on the miser’s wall, the fire grille in the gambler’s den—even the wedding ring is a fetter. But Tom has always dreamed of escape, of grand solutions and bottomless wealth. Here those dreams come to haunt him in the fantasies of the other debtors: the old man’s schemes to solve the national debt; the harness of feathers that might let a man soar free like Icarus, only to fall in the heat of the sun and drown in the sea of despair; the crazy alchemist trying to make gold. These are the dreamers. The realists are the sturdy turnkey, the eyeless old wife whispering like an angry sybil in Tom’s ear, the stout and stalwart women slapping Sarah’s hands and offering smelling salts.

The final plates of A Rake’s Progress outreach any moralizing. In the Fleet, Hogarth shows a fearful borderland, a man lost in an inner desert more terrible than the jarring, grasping, elbowing crowd around him. He has become locked into himself and can only plunge deeper, into madness itself (255).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 7

Dobson, Austin. William Hogarth. (1907)

The next scene is in the Fleet; the last in Bedlam. In one he is a poor distracted wretch, dunned by the gaoler for “garnish” (Entrance fees or perquisites exacted from incoming prisoners by the prison officials), pestered by the unpaid pot-boy, deafened by the rancorous virago, his wife, and overwhelmed by Mr. Manager Rich’s letter returning his manuscript:--“Sr. I have read yr. Play & find it will not doe” (This has been regarded as ridicule of John Rich, whose want of education was notorious. It was probably Hogarth’s blunder, as his own spelling was often faulty.) (43).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 7

Quennell, Peter. Hogarth’s Progress. (1955)

Through narrowing spirals of misfortune, Tom Rakewell reaches a debtor’s prison. Here he is plagued by the reproaches of his wife, distressed by the importunities of the devoted Sarah, who visits the gaol with his illegitimate child only to collapse in a deathly swoon, and vexed by the demands of the gaoler and the gaoler’s pot-boy. He has tried his hand at writing a comedy; but Rich, the successful actor-manager, has returned it with a curt note. The smooth foolish physiognomy of his youth has now been carved by experience into the mask of a haggard middle-aged man. It is not surprising that, in the end, he should lose is grip on sanity, and he removed from the gloom of a prison to the squalor and confusion of a public madhouse (133).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 7

Lichtenberg, G. Ch. Lichtenberg’s Commentaries on Hogarth’s Engravings. (1784-1796). Translated from the German by Innes and Gustav Herdan (1966)

Sir William Hamilton, in his report of the last eruption of Vesuvius in the Summer of 1794, remarks that around the foot of that dangerous mountain and the neighbouring Somma, and thus within a circumference of about SO Italian or 8 German miles, there lived more people than on any plot of similar area in the whole of Europe. People seemed to crowd around the volcano's mouth like gnats around a flame; even if some of them burned their wings, others always came to take their place; so little did they avoid or realize the peril. This is indeed curious, and yet far less curious than that, in a country of freedom and plenty like England, just those houses should be most crowded where everybody who enters must first make at the door his votum obedientiae passivae et frugalitatis. And that all the scheming and effort of a good part of that happy throng should lead to just the sort of life that would one day end in such a monastery. A plan like this rarely miscarries if one is seriously intent upon it, and of how it can be most easily effected, we have a clear example in the life of our hero.

He has just been accepted, has made his vow, and is still preoccupied with those importunities of the heart which such changes usually produce in people of the true anointing. It is not long since he left the world. His bed lies there, not yet unpacked. A grill is tied on to it. That is all he has taken with him from the secular world. If only his conscience is at peace! I am almost afraid that in Rakewell the outer man has not yet succeeded in coming to terms with the inner one. In that case, the grid-iron tied to the bed may be, if not the model, at least the symbol of the bedstead, upon which he intends to roast himself alive at night, on his own memories.

What sort of monastery it is, the reader will already have guessed from the grated door and the Chamberlain's key which hangs from the hip of Pater Cubicularius. Rakewell is in prison, more precisely in the Fleet, also a sort of Lombard, distinguishable from the usual institutes of this sort only by its being not so much a prison for movables as for the prime movers themselves, and roughly what we call in Germany Schuldturm, a 'debtors prison'.

Earlier, there was mention of certain blessings and prophecies which might be fulfilled in our hero. And here they are. Here he is now writhing under the lash of his deserved misfortune—tout beau! Would it be possible to depict sorrow, misery, and awakened conscience with all the two-edged torture of fear and remorse in a debauched good- for-nothing more strongly than here? He is not yet articulate. In place of words, however, a wave of eloquent trembling runs through his emaciated limbs, from below upwards. The hand propped upon the knees is lifted with deep significance, and is followed in sympathy by the foot, just as the corrugated brow draws after it the eyelids and the shoulders; the stream flows upwards. But this is no picture of uplift, or at least it is only the sort which is inseparable from gestures expressive of a deep fall, impotence and destruction. Everything falls only the deeper, and thus he pronounces his own sentence of damnation, and through despair becomes his own hangman. What does he see now with those staring eyes? Perhaps the dancing master or the gardens or the race-horses? Or does he see absolutely nothing? Or does his ear listen to the melody of Orpheus who tamed the beasts? Oh, if only he still had the little gold snuff-box! Here the beasts are tamed more economically! We shall see how it is done. The means are drastic.

Next to him stands the little acquisition which he made in the Church of Mary-le-Bone, his dear wife, albeit somewhat changed. Her mouth, which there curved gently into a tender smile, like Luna a few days after her rebirth, could here with its full black circle indicate the new moon in some village almanack. Yet, what is more, her whole head which reminded us of the friendly and peaceful crunching of a dainty squirrel has been transformed here into a lion's head with mane, and with jaws that would crack human skulls like hazel nuts. It is quite certain that after the wedding things are rather different from what they were before. Here she is using her little fists, which have just hurriedly attended to the arrangement other own hair, for effecting a slight alteration in that other husband. To be exact, she probably only intends to help his memory a little over certain details concerning her dowry, which could not be achieved by that method without a disturbance of the capillary system.

To be sure, she proceeds very properly. She first applies her left fist to his shoulder, so as to shake loose his firmly embedded thoughts, and as soon as she sees that they are afloat, starts an attack with the right fist just in the place where they are swimming, to set them off in the new direction. That is how one even imparts polarity to iron. It cannot fail. But all this, troublesome though it may be in such circumstances for a man of feeling, is by no means so disagreeable to the poor devil as the terrific salvo of grape-shot which his better half's tongue shoots out of that dark thieves' kitchen into his ears and his heart. Here he indeed deserves our pity. This is too hard on him, one would be inclined to say, if it were not so natural, and if something that is natural could also be hard. All authors writing about the defensive system of the fair sex, and of its military operations in the matrimonial campaign, speak of that part of its artillery as of a sort of miracle. Fielding, one of the most illustrious, remarks that the wisest men have trembled before it, and that even the most valiant who were capable of looking in cold blood into the mouth of a 24-pounder had shrunk back with pitiful face if required to look into the mouth of such a mortar. If the wisest and most valiant among men have done so, what must he now be suffering who is neither the one nor the other, and who in addition is not even in a position to slink away? And yet this is by no means all. While the woman attacks him from in front and upon the right flank, another enemy attacks his left flank, and a third his rear, while at the same time he is notified by an acquaintance in a friendly letter that his main arsenal has been blown up. Indeed under such circumstances no one but Socrates or Charles XII could sit otherwise than does Rakewell here.

A boy, or whatever sort of creature it is (for in the formation of his physiognomy insolence seems to have been working for at least a quarter of a century), has brought him the porter as requested, though for the time being only to look at. Without barter the poor wretch, languishing for a drink, will not have a taste of it, and there is nothing left to barter! Even the shoe buckles seem to be only mourning buckles, whose lacquer or blueing has already been mourned away. Behind him stands the executioner under-turnkey! To judge from the book which is resting on his arm, he wants to call in the garnish money, the 'welcome' from the prisoner. The face, which the fellow also offers for sale, seems to be one of the best which he is capable of producing, in the interests of the transaction. It is a pity that Rakewell does not see it, but he would not have been able to buy it in any case. The insolvency which can no longer pay for a can of beer will probably be content with such faces as insolence presents gratis. Does the reader notice the conclusion, in forma iuris, which is drawn here? A poor devil who has been put in prison be- cause he cannot pay is required to pay for being in prison. Just like this, a few years ago, did the French deal with the good city of Worms, merely because, as they said, that city had offended the good city Worms herself.

And now for the bundle of papers and the note containing the news of the blown-up powder-magazine! This blow is one of the hardest, and acts as powerfully upon his spirit as does the fire released by his prison mate upon his heart. It is unbearable. The note reads thus: 'Sir, I have read your Play and find it will not doe. Yrs. J. R. ... ch. The explanation is briefly as follows: this Mr Rich was then director and manager of one of the largest London theatres. Rakewell had submitted to him the MS. marked Act 4. It contains a play which he had written in his leisure hours under the auspices of the tenth Muse, who despite the decay of all the remaining nine still holds her own in England as well as in Germany, I mean Paupertas audax. He had hoped to bid farewell to life if not as a rich man, at least with the splendida miseria of a modern bel esprit. All these hopes are now dashed to the ground at one blow by the letter. All is over now, flown away, gone—'it will not do'. What could the theme of that play have been? The Rake's Progress, or The Road to Ruin? Not very likely, for it is in the nature of a bad author not to know himself, and never to write about things which he alone could write about.

What a picture this to nail up on the walls where pride of authorship draws many a bill of exchange upon the Muses, each of which is returned in the end like this one, with an insulting objection. Oh! all ye who count upon a high reward from the Muses in your old age, come over here to the torture bench of this cashiered genius; he too counted upon that reward. Such is the fate of thousands. Consider, dearest friends., that since calamus has other meanings in latin than 'blade' or 'reed', so calamitas means more than 'damage done by hail'. Since the one includes 'goose-quill’ among its meanings, the number of calamities for authors, and sometimes for readers too, grows to infinity. The minor misfortune, which in the Golden and Silver ages of the world could only be inflicted upon individuals by ruined crops, now in the days of its senility is brought about with ten-fold intensity by writing quills, and inflicted upon whole generations. What, after all, was a little passing scarcity through hail compared with our present continuous indigestion from the heavy, black, sour bread of the Muses by means of which many a citizen of the world of learned beggars drags himself painfully along, on true calami of legs and with cheeks the colour of his laurels?

It is a thousand pities that, through a criminal misuse, one of the most powerful means for improving the human race has been rendered completely ineffective, I mean instruction by wall-posters. A group like this one, posted up in the declination-and-conjugation stable, would be of infinite advantage to the young. But I am afraid it is all over with that sort of thing, just as it will soon be all over with everything. The general endeavour of the human race to make the means the end must be regarded as a second Fall through which in the end everything will succumb. Is there not already a class of learned men called friends of books, and are they not merely insects with wing cases, but without wings? Has not the timekeeping of our wise ancestors become nowadays merely a wearing of watches? Nay, do we not hang two of them now, one opposite the other like sentries, in a region where perhaps since the fig leaf was removed from there, time and hour have never been worse kept than between those two time-keepers?

Opposite Rakewell a woman is fainting; a man in négligé strives to break her fall, or at least to keep it within the limits of decency, and two born doctoresses have loosened her stays and are trying to revive her. The resuscitative method of the one appears almost hyperphysical, at least not wholly of this world, nor is the cunning in her face. The swooning woman is the same Sarah Young who appears now for the fourth time, and the crying child is a little Miss Rakewell, who is here in visible form for the second time. Thus Sarah Young follows her faithless seducer even into jail. Difficult though his complete deliverance may now be, it is easy to bring relief to one for whom a glass of porter is a boon. She must have been well aware of it. That, as is generally believed, her first sight of the dreadful decay of her former lover could by itself have effected her collapse, I do not credit. The cause was undoubtedly a moral one, but here evidently intensified rather powerfully by physicochemical causes. For it is said that in England the air in places where people are imprisoned, who, through no fault of their own, are suffering from lack of gold, is not a whit better than in the secret kitchens where gold is made, and un- fortunately this cell serves both purposes. Cold sweat over squandered gold mingles here, as we shall hear presently, with the sulphuric dew of mercury which usually accompanies the Aurora of the newly created metal-of-metals when it rises from the crucible; however, the moral cause is by far the stronger. Besides, it could not have been the mere sight of her destitute lover, since Sarah Young has walked from the door to the place where she collapsed, and it is probable that she had even been sitting there for some time. I believe, therefore, that she fell by a salvo from the thieves' kitchen at Rakewell's right wing. Probably she and her child were recognized by Madame Rakewell who, suddenly loaded with 'Bastard! Whore! and Witch!', and let fly, which of course upon a creature of Sarah Young's character must have acted like wheelwright nails and shell splinters. As she falls there occur a few circumstances which one hardly dares to notice, but which, however, undoubtedly occupy a rather high place among the sufferings which here break loose upon the sinner, Rakewell. The bared bosom of, at least, Hogarthian beauty, the position of the foot, and in general the whole collapse with the chair, which was perhaps more dangerous to certain eyes than it appears now to ours, are certainly not drawn here for nothing. For Rakewell, who sits just opposite, they must necessarily have given rise to comparisons, which every reader has probably made already himself, between what he once so light-heartedly cast away, and what he now calls his own upon the right wing. Even supposing that he makes that comparison entirely upon the scales of the senses, which with him seem to be slightly out of action, yet conscience, once awakened, will always find on its own scales sufficient turning for despair. There is much more here than Mr Rich's note: all might have been well, but now it is all over; it is gone; it will do no more!

Thus far goes the thread of history in the picture. The rest are ornaments but of such a masterly kind that we must regret there are not more of them. Here Hogarth would have been completely in his element. The man who watches over Sarah Young's decency we have called 'the man in négligé and hope the reader will have nothing against the expression. The wig is, like Rakewell's and like his angel's hair, governed merely by hazard; a long time unpowdered, but the more frequently de- powdered, probably by mere forceful hitting of, and curling round, the chair back, as if upon a flax-spindle. His beard seems to keep pace with the calendar months and is fairly far advanced 'in its 'teens'. To judge from his physiognomy he must be a very low type, but his dressing-gown persuades me to recognize him as an author. The elbow has actually written its way out, and the writing sleeve suggests the meditation sleeve, which must carry the head as well. Although trousers are not of special importance where the dressing-gown is master of the house, yet one will rarely find a pair which shuns the light so utterly as these do here. They come to an end around the knee, one does not quite know how, almost with a mere etcetera. It rather looks as if they had been a pair of pantaloons of which the lower parts had been gradually used up in the service of the uppers. It is interesting to note here that at that time people already mourned for shoe buckles, at least in the London debtors' prisons. The bellows-blower position in which the prisoner appears has, apart from the purpose of supporting the fainting woman, another two-fold one. For in the first place, the hands being occupied, the trousers have evidently lost their primary support. In order to prevent their immediately taking the place of the cut-off parts, some remedy was called for, and that consisted in the thigh adopting the horizontal position. In the second place, the man had got hold somewhere of a few bundles of manuscript, which now take themselves off as well; three of them are already lying for the greater part on the ground, soon to be followed by the fourth, though this one he seems to be still trying to grip. Although none of it is breakable, this gives a bad impression, and in the end everything would have to be gathered up again. This little disorder is of extraordinary value to an inquisitive spectator. We learn here the owner of the many-cornered elbow. On one of the bundles we read the words :'Being a new Scheme for paying ye Debts of ye Nation by T. L., now a prisoner in the Fleet.' It is thus by an author who cannot pay his own debts. The idea has become as famous as the spider's web over the Poors' Box, probably because it is, like that, as clear as it is pertinent. Also the frailties they denounce are equally common. To deny others the help one could have given without any harm to oneself is as common in human beings as it is to present them, in times of distress, with rules of conduct which have brought the donor himself to bankruptcy. Such a Mr L. is said to have really existed at that time. This does not surprise me; there are always people like that, perhaps with other initials, and with other projects! Oh there is no country and no Faculty free of them: mutato nomine de Te, and so on.

Back against the wall sits another, already mutato nomine, I mean the half-charred alchemist who has a little pot upon the fire not only for the benefit of the nation but of the whole human race. The philosophical peace in that man's face and in his whole position really has something very pleasing about it; one sees he has learned to wait, an art which in no occupation in the world is more necessary than in the making of gold. That he hears and sees nothing at all of what is going on around him he has in common with all the people who through seeing and hearing have become immortal. The friendship between the man and his furnace is indeed touching if one realizes that both have finished up here only through their connection, and that each without the other might perhaps have been something much better. Yet they cling together as if made of one piece (they almost look like it) and feed each other with hopes and coal until the day when the great problem will be solved. That day cannot possibly be far off. The flue passing through the barred window is too well designed—it must function; the apparatus, on the other hand, through which the rare product is to be transferred into the bottle, is not specially good—it is bound to fail. Whether Hogarth was himself an expert in these matters, or whether he followed here the instructions of an expert, or whether the inspiration of genius guided his stylus aright to an end which he himself could not have conceived, I leave undecided. It may suffice that the circulus in destillando cannot be mistaken; the receiver is nearer the fire than the retort, and while each vies with the other for possession of the tincture, everything goes up in smoke, and there we leave the solution of the problem; of course in a sense which nobody imagined when the question was posed, but which is an answer to that question all the same. Through the barred window something protrudes which one might almost take for an instrument with which to ask advice of the planets in complex chemical investigations, if the stand were not of all-too-limited use and altogether too uncomfortable for persons accustomed to observe with the right eye. Also the object-end of the telescope is somewhat too near the furnace chimney. Probably it is not a tube at all, but merely a rough, solid cylinder with which to push open or close the heavy window shutter. Up above on the right stand some numbered vessels; they seem to be light since they perch themselves so high up. Whether this also applies to the books of the hanging library is not so easy to decide; the title 'Philosophica' makes it at least doubtful. It is a wonder that with this library Hogarth has missed the opportunity of rendering certain con- temporary works of his countrymen the two-fold favour of treating them as prisoners in the Fleet and as the secret confidants of the alchemist and universal doctor. If we consider the whole design of the stove, which is really not without elegance, and if we observe how everything fits just into that comer by the window, we can hardly avoid the idea that the Wardens of the Fleet provide chemical stoves in the cages reserved for gold-makers, just as one hangs rings in parrots' cages. If this is not so, it is at least a suggestion deserving the turnkey's attention. He could certainly count upon an annual oven-dividend. These, then, were two fanciful types in the Fleet, and there above the bedstead lies the shed skin of a third. For this one the arts of chemistry and of high finance were too low-grade; he hastened to Olympus upon the eagle pinions of an Ode, but stuck fast, as so often happened to his prototype, between the Heaven of the bedstead and the ceiling, with head pointing downwards. The apparatus is excellent; it must have roared and thundered bravely. It is a pity that it was so soon over. If the feathers themselves were so firmly fixed as are the wings on the body, then the man had nothing to fear from the proximity of the sun, in contrast with his precursor Icarus, for there are buckles and oxhide in plenty. Thus with this apparatus its inventor probably rose from the bosom of his family and above the base monotony of his official duties paralysing mind and body, up above the heaven of his bedstead in the debtors' prison. If the financier T. L. had stood slightly farther back, and nearer the alchemist, and if the left wing had been spread out slightly wider, this group would be the most perfect Sub umbra alarum tuarum that has ever been drawn.

Lastly, I may mention that Rakewell has brought with him a rather fine cane chair, probably the last of a dozen, and that the clock on his right stocking is very noticeably shorter than on his left. Thus they are either from two different pairs, or one of them has already started, from well-known causes, to serve from above downwards, just like the trousers of the financier from below upwards (253-262).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 7: Alchemist

His cellmates are an alchemist vainly trying to produce gold (perhaps symbolizing Tom’s own futile efforts to make money with his writing) and a projector whose imprisonment for debt is ironically underscored by his lofty plans to solve the financial problems of the nation. Hogarth is suggesting that, to solve England’s problems, one must concentrate on reforming the individual.

A Rake's Progress: Plate 7: Alchemist

Shesgreen

The fellow in the corner with the nightcap (who has been there a long time if we are to judge by his elaborate still and chimney) is a mad alchemist. He is too absorbed in his furnace project (probably attempting to turn metal into gold) to notice what transpires around him. His telescope sticks out through the prison bars; three mixing pots stand beside his meager library; a paper inscribed “Philosophical” protrudes from one volume (34).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 7: Alchemist

Ireland

A chemist in the background, happy in his views, watching the moment of projection, is not to be disturbed from his dream by anything less than the fall of the roof or the bursting of his retort; and if his dream affords him the felicity, why should he be awakened? (152)

A Rake's Progress: Plate 7: Alchemist

Lichtenberg

Back against the wall sits another, already mutato nomine, I mean the half-charred alchemist who has a little pot upon the fire not only for the benefit of the nation but of the whole human race. The philosophical peace in that man's face and in his whole position really has something very pleasing about it; one sees he has learned to wait, an art which in no occupation in the world is more necessary than in the making of gold. That he hears and sees nothing at all of what is going on around him he has in common with all the people who through seeing and hearing have become immortal. The friendship between the man and his furnace is indeed touching if one realizes that both have finished up here only through their connection, and that each without the other might perhaps have been something much better. Yet they cling together as if made of one piece (they almost look like it) and feed each other with hopes and coal until the day when the great problem will be solved. That day cannot possibly be far off. The flue passing through the barred window is too well designed—it must function; the apparatus, on the other hand, through which the rare product is to be transferred into the bottle, is not specially good—it is bound to fail. Whether Hogarth was himself an expert in these matters, or whether he followed here the instructions of an expert, or whether the inspiration of genius guided his stylus aright to an end which he himself could not have conceived, I leave undecided. It may suffice that the circulus in destillando cannot be mistaken; the receiver is nearer the fire than the retort, and while each vies with the other for possession of the tincture, everything goes up in smoke, and there we leave the solution of the problem; of course in a sense which nobody imagined when the question was posed, but which is an answer to that question all the same. Through the barred window something protrudes which one might almost take for an instrument with which to ask advice of the planets in complex chemical investigations, if the stand were not of all-too-limited use and altogether too uncomfortable for persons accustomed to observe with the right eye. Also the object-end of the telescope is somewhat too near the furnace chimney. Probably it is not a tube at all, but merely a rough, solid cylinder with which to push open or close the heavy window shutter. Up above on the right stand some numbered vessels; they seem to be light since they perch themselves so high up. Whether this also applies to the books of the hanging library is not so easy to decide; the title 'Philosophica' makes it at least doubtful. It is a wonder that with this library Hogarth has missed the opportunity of rendering certain con- temporary works of his countrymen the two-fold favour of treating them as prisoners in the Fleet and as the secret confidants of the alchemist and universal doctor (260-261).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 7: Daughter

Their daughter, with a face like a small adult, pragmatically attempts to rouse her mother from her spell.

A Rake's Progress: Plate 7: Daughter

Shesgreen

Sarah Young faints in compassion at his plight. A companion shoves her head toward a bottle of smelling salts; another slaps her hand, while her daughter seems to rebuke the mother for her conduct (34).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 7: Daughter

Ireland

To crown this catalogue of human tortures, the poor girl whom he deserted is come with her child,--perhaps to comfort him, to alleviate his sorrows, to soothe his sufferings; but the agonizing view is too much for agitated frame; shocked at the prospect of that misery which she cannot remove, every object swims before her eyes, a film covers the sight, the blood forsakes her cheeks, her lips assume a pallid hue, and she sinks to the floor if the prison in temporary death (150).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 7: Daughter

Lichtenberg

the crying child is a little Miss Rakewell, who is here in visible form for the second time (258).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 7: Icarus

The dreams of all involved are as deadly as Icarus’s attempt to fly to the sun. A pair of wings in the corner of the plate make this mythological link explicit.

A Rake's Progress: Plate 7: Icarus

Shesgreen

Above his canopy rests a pair of wings. Like the rake, his [the alchemist’s] plans to soar beyond his natural realm have brought him only imprisonment and insanity (34).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 7: Icarus

Ireland

Over the group are a large pair of wings, with which some emulator of Dedalus intended to escape from his confinement; but finding them inadequate to the execution of his project, has placed them upon the tester of his bed. They would not exalt him to the regions of the air, but they o’er-canopy him on earth (151-152).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 7: Icarus

Lichtenberg

These, then, were two fanciful types in the Fleet, and there above the bedstead lies the shed skin of a third. For this one the arts of chemistry and of high finance were too low-grade; he hastened to Olympus upon the eagle pinions of an Ode, but stuck fast, as so often happened to his prototype, between the Heaven of the bedstead and the ceiling, with head pointing downwards. The apparatus is excellent; it must have roared and thundered bravely. It is a pity that it was so soon over. If the feathers themselves were so firmly fixed as are the wings on the body, then the man had nothing to fear from the proximity of the sun, in contrast with his precursor Icarus, for there are buckles and oxhide in plenty. Thus with this apparatus its inventor probably rose from the bosom of his family and above the base monotony of his official duties paralysing mind and body, up above the heaven of his bedstead in the debtors' prison. If the financier T. L. had stood slightly farther back, and nearer the alchemist, and if the left wing had been spread out slightly wider, this group would be the most perfect Sub umbra alarum tuarum that has ever been drawn (261-262).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 7: Projector

His cellmates are an alchemist vainly trying to produce gold (perhaps symbolizing Tom’s own futile efforts to make money with his writing) and a projector whose imprisonment for debt is ironically underscored by his lofty plans to solve the financial problems of the nation. Hogarth is suggesting that, to solve England’s problems, one must concentrate on reforming the individual.

A Rake's Progress: Plate 7: Projector

Paulson, Hogarth's Graphic Works

The unkempt man who is helping Sarah drops a scroll on which is written "Being a New Scheme for paying ye Debts of ye Nation by T: L: now a prisoner in the Fleet," and another marked "... Debts" (a memory of the South Sea Company) (169).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 7: Projector

Ireland

The wretched, squalid inmate who is assisting the fainting female, bears every mark of being naturalized to the place: out of his pocket hangs a scroll, on which is inscribed, “A scheme to pay the national debt, by J.L. now a prisoner in the Fleet.” So attentive was this poor gentleman to the debts of the nation that he totally forgot his own (151).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 7: Projector

Uglow

And beside her stands a wry reminder of men like Hogarth’s own father, a puzzled, disheveled figure with a cheap wig aslant on his dark hair, his blunt, stubbly face gawping in distress; from the pocket of his dressing-gown, full of holes, a paper floats to the ground, “A New Scheme for solving the Debts of the Nation” (255)

A Rake's Progress: Plate 7: Projector

Lichtenberg

The man who watches over Sarah Young's decency we have called 'the man in négligé and hope the reader will have nothing against the expression. The wig is, like Rakewell's and like his angel's hair, governed merely by hazard; a long time unpowdered, but the more frequently de- powdered, probably by mere forceful hitting of, and curling round, the chair back, as if upon a flax-spindle. His beard seems to keep pace with the calendar months and is fairly far advanced 'in its 'teens'. To judge from his physiognomy he must be a very low type, but his dressing-gown persuades me to recognize him as an author. The elbow has actually written its way out, and the writing sleeve suggests the meditation sleeve, which must carry the head as well. Although trousers are not of special importance where the dressing-gown is master of the house, yet one will rarely find a pair which shuns the light so utterly as these do here. They come to an end around the knee, one does not quite know how, almost with a mere etcetera. It rather looks as if they had been a pair of pantaloons of which the lower parts had been gradually used up in the service of the uppers. It is interesting to note here that at that time people already mourned for shoe buckles, at least in the London debtors' prisons. The bellows-blower position in which the prisoner appears has, apart from the purpose of supporting the fainting woman, another two-fold one. For in the first place, the hands being occupied, the trousers have evidently lost their primary support. In order to prevent their immediately taking the place of the cut-off parts, some remedy was called for, and that consisted in the thigh adopting the horizontal position. In the second place, the man had got hold somewhere of a few bundles of manuscript, which now take themselves off as well; three of them are already lying for the greater part on the ground, soon to be followed by the fourth, though this one he seems to be still trying to grip. Although none of it is breakable, this gives a bad impression, and in the end everything would have to be gathered up again. This little disorder is of extraordinary value to an inquisitive spectator. We learn here the owner of the many-cornered elbow. On one of the bundles we read the words :'Being a new Scheme for paying ye Debts of ye Nation by T. L., now a prisoner in the Fleet.' It is thus by an author who cannot pay his own debts. The idea has become as famous as the spider's web over the Poors' Box, probably because it is, like that, as clear as it is pertinent. Also the frailties they denounce are equally common. To deny others the help one could have given without any harm to oneself is as common in human beings as it is to present them, in times of distress, with rules of conduct which have brought the donor himself to bankruptcy. Such a Mr L. is said to have really existed at that time. This does not surprise me; there are always people like that, perhaps with other initials, and with other projects! Oh there is no country and no Faculty free of them: mutato nomine de Te, and so on (259-260).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 7: Rake

Hogarth allows his tale to take a melodramatic turn in this seventh plate. Tom no longer appears as the licentious gambling rake. Instead, he is in debtors’ prison; a rejection from a publisher equates him with the other misunderstood and failed dreamers.

His wife rightfully admonishes his wastefulness; his frustrated posture reveals his realization that he has run out of chances.

A Rake's Progress: Plate 7: Rake

Shesgreen

The promise of Plate IV is here fulfilled and the rake, like the harlot before him, is jailed (for debt). The scene is the crude stone interior of the Fleet, a debtors’ prison. The rake, slumped listlessly forward, his face filled with despair and anomie, besieged on all sides, gestures helplessly with his hands and feet. His last desperate attempt to earn money by writing a play has failed; beside him lies a curt rejection: “Sr. I have read your Play & find it will not doe yrs. J.R. .h..” The misspelled “doe” seems to be a hit at the theater manager and pantomimist John Rich. Rakewell is now so destitute that he cannot give the turnkey the “garnish money” or pay the perturbed youth for a mug of beer. While his shrewish wife assaults him (34).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 7: Rake

Paulson, Hogarth's Graphic Works

Having lost all his wife's money in the gambling house, Rakewell is confined in a debtors' prison (the Fleet Prison). His old one-eyed wife (who seems to have lost some weight) harangues him; Sarah Young, accompanied by their child, has arrived and fallen into convulsions—perhaps as a result of the latest bad news. In those days every gentleman wrote a play, and so Rakewell has thus attempted to recoup his losses; his manuscript has just been returned to him ("Act 4" is legible in the roll of manuscript) with a letter: "Sr I have read your Play & find it will not doe y8 J. R. .h" (John Rich, manager of the Covent Garden Theatre). This latest blow may account for Sarah's convulsions as well as Rakewell's expression. Finally, the turnkey demands "Garnish money" (as his ledger shows), and a boy demands money for a pot of beer he has brought him (168-169).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 7: Rake

Ireland

Our improvident spendthrift is now lodged in that dreary receptacle of human misery—a prison. His countenance exhibits a picture of despair; the forlorn state of his mind is displayed in every limb, and his exhausted finances by the turnkey’s demand of prison fees not being answered, and the boy refusing to leave a tankard of porter unless he is paid for it.

We learn by a letter on the table, that a play which he sent for the manager’s inspection “will not doe” (I am afraid that Mr. William Hogarth was ignorant of spelling, for his warmest admirers to contest the point any longer); and we see by the enraged countenance of his wife, that she is violently reproaching him for having deceived and ruined her (149-150).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 7: Rake

Uglow

When Tom himself sits helpless in the Fleet with all his money gone, he wears that same fierce inner gaze [see Plate VI], and another small boy reminds him of his drink and holds out his hands for coins.

Hogarth’s drawing always recalls the theatre; a stage gesture of rape, and actor’s broad presentation of misery and madness. But in the Fleet scene Tom’s pose is a startling physical contrast of introspective despair, in the stillness of his head and shoulders, and the jerking agitation of his restless hands and feet (255).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 7: Rake

Dobson

In one he is a poor distracted wretch, dunned by the gaoler for “garnish” (Entrance fees or perquisites exacted from incoming prisoners by the prison officials), pestered by the unpaid pot-boy, deafened by the rancorous virago, his wife, and overwhelmed by Mr. Manager Rich’s letter returning his manuscript:--“Sr. I have read yr. Play & find it will not doe” (This has been regarded as ridicule of John Rich, whose want of education was notorious. It was probably Hogarth’s blunder, as his own spelling was often faulty.) (43).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 7: Rake

Quennell

Through narrowing spirals of misfortune, Tom Rakewell reaches a debtor’s prison. Here he is plagued by the reproaches of his wife, distressed by the importunities of the devoted Sarah, who visits the gaol with his illegitimate child only to collapse in a deathly swoon, and vexed by the demands of the gaoler and the gaoler’s pot-boy. He has tried his hand at writing a comedy; but Rich, the successful actor-manager, has returned it with a curt note. The smooth foolish physiognomy of his youth has now been carved by experience into the mask of a haggard middle-aged man. It is not surprising that, in the end, he should lose is grip on sanity, and he removed from the gloom of a prison to the squalor and confusion of a public madhouse (133).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 7: Rake

Lichtenberg

And here they are. Here he is now writhing under the lash of his deserved misfortune—tout beau! Would it be possible to depict sorrow, misery, and awakened conscience with all the two-edged torture of fear and remorse in a debauched good- for-nothing more strongly than here? He is not yet articulate. In place of words, however, a wave of eloquent trembling runs through his emaciated limbs, from below upwards. The hand propped upon the knees is lifted with deep significance, and is followed in sympathy by the foot, just as the corrugated brow draws after it the eyelids and the shoulders; the stream flows upwards. But this is no picture of uplift, or at least it is only the sort which is inseparable from gestures expressive of a deep fall, impotence and destruction. Everything falls only the deeper, and thus he pronounces his own sentence of damnation, and through despair becomes his own hangman. What does he see now with those staring eyes? Perhaps the dancing master or the gardens or the race-horses? Or does he see absolutely nothing? Or does his ear listen to the melody of Orpheus who tamed the beasts? Oh, if only he still had the little gold snuff-box! Here the beasts are tamed more economically! We shall see how it is done. The means are drastic.

Next to him stands the little acquisition which he made in the Church of Mary-le-Bone, his dear wife, albeit somewhat changed. Her mouth, which there curved gently into a tender smile, like Luna a few days after her rebirth, could here with its full black circle indicate the new moon in some village almanack. Yet, what is more, her whole head which reminded us of the friendly and peaceful crunching of a dainty squirrel has been transformed here into a lion's head with mane, and with jaws that would crack human skulls like hazel nuts. It is quite certain that after the wedding things are rather different from what they were before. Here she is using her little fists, which have just hurriedly attended to the arrangement other own hair, for effecting a slight alteration in that other husband. To be exact, she probably only intends to help his memory a little over certain details concerning her dowry, which could not be achieved by that method without a disturbance of the capillary system.

To be sure, she proceeds very properly. She first applies her left fist to his shoulder, so as to shake loose his firmly embedded thoughts, and as soon as she sees that they are afloat, starts an attack with the right fist just in the place where they are swimming, to set them off in the new direction. That is how one even imparts polarity to iron. It cannot fail. But all this, troublesome though it may be in such circumstances for a man of feeling, is by no means so disagreeable to the poor devil as the terrific salvo of grape-shot which his better half's tongue shoots out of that dark thieves' kitchen into his ears and his heart. Here he indeed deserves our pity. This is too hard on him, one would be inclined to say, if it were not so natural, and if something that is natural could also be hard. All authors writing about the defensive system of the fair sex, and of its military operations in the matrimonial campaign, speak of that part of its artillery as of a sort of miracle. Fielding, one of the most illustrious, remarks that the wisest men have trembled before it, and that even the most valiant who were capable of looking in cold blood into the mouth of a 24-pounder had shrunk back with pitiful face if required to look into the mouth of such a mortar. If the wisest and most valiant among men have done so, what must he now be suffering who is neither the one nor the other, and who in addition is not even in a position to slink away? And yet this is by no means all. While the woman attacks him from in front and upon the right flank, another enemy attacks his left flank, and a third his rear, while at the same time he is notified by an acquaintance in a friendly letter that his main arsenal has been blown up. Indeed under such circumstances no one but Socrates or Charles XII could sit otherwise than does Rakewell here (254-255).

And now for the bundle of papers and the note containing the news of the blown-up powder-magazine! This blow is one of the hardest, and acts as powerfully upon his spirit as does the fire released by his prison mate upon his heart. It is unbearable. The note reads thus: 'Sir, I have read your Play and find it will not doe. Yrs. J. R. ... ch. The explanation is briefly as follows: this Mr Rich was then director and manager of one of the largest London theatres. Rakewell had submitted to him the MS. marked Act 4. It contains a play which he had written in his leisure hours under the auspices of the tenth Muse, who despite the decay of all the remaining nine still holds her own in England as well as in Germany, I mean Paupertas audax. He had hoped to bid farewell to life if not as a rich man, at least with the splendida miseria of a modern bel esprit. All these hopes are now dashed to the ground at one blow by the letter. All is over now, flown away, gone—'it will not do'. What could the theme of that play have been? The Rake's Progress, or The Road to Ruin? Not very likely, for it is in the nature of a bad author not to know himself, and never to write about things which he alone could write about (256-257).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 7: Sarah

Paulson, Hogarth's Graphic Works

Sarah Young, accompanied by their child, has arrived and fallen into convulsions—perhaps as a result of the latest bad news (169).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 7: Sarah

Ireland

To crown this catalogue of human tortures, the poor girl whom he deserted is come with her child,--perhaps to comfort him, to alleviate his sorrows, to soothe his sufferings; but the agonizing view is too much for agitated frame; shocked at the prospect of that misery which she cannot remove, every object swims before her eyes, a film covers the sight, the blood forsakes her cheeks, her lips assume a pallid hue, and she sinks to the floor if the prison in temporary death (150).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 7: Sarah

Uglow

Opposite him, Sarah has fainted, while their child tugs her skirt (255).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 7: Sarah

Lichtenberg

Opposite Rakewell a woman is fainting; a man in négligé strives to break her fall, or at least to keep it within the limits of decency, and two born doctoresses have loosened her stays and are trying to revive her. The resuscitative method of the one appears almost hyperphysical, at least not wholly of this world, nor is the cunning in her face. The swooning woman is the same Sarah Young who appears now for the fourth time.

Thus Sarah Young follows her faithless seducer even into jail. Difficult though his complete deliverance may now be, it is easy to bring relief to one for whom a glass of porter is a boon. She must have been well aware of it. That, as is generally believed, her first sight of the dreadful decay of her former lover could by itself have effected her collapse, I do not credit. The cause was undoubtedly a moral one, but here evidently intensified rather powerfully by physicochemical causes. For it is said that in England the air in places where people are imprisoned, who, through no fault of their own, are suffering from lack of gold, is not a whit better than in the secret kitchens where gold is made, and un- fortunately this cell serves both purposes. Cold sweat over squandered gold mingles here, as we shall hear presently, with the sulphuric dew of mercury which usually accompanies the Aurora of the newly created metal-of-metals when it rises from the crucible; however, the moral cause is by far the stronger. Besides, it could not have been the mere sight of her destitute lover, since Sarah Young has walked from the door to the place where she collapsed, and it is probable that she had even been sitting there for some time. I believe, therefore, that she fell by a salvo from the thieves' kitchen at Rakewell's right wing. Probably she and her child were recognized by Madame Rakewell who, suddenly loaded with 'Bastard! Whore! and Witch!', and let fly, which of course upon a creature of Sarah Young's character must have acted like wheelwright nails and shell splinters. As she falls there occur a few circumstances which one hardly dares to notice, but which, however, undoubtedly occupy a rather high place among the sufferings which here break loose upon the sinner, Rakewell. The bared bosom of, at least, Hogarthian beauty, the position of the foot, and in general the whole collapse with the chair, which was perhaps more dangerous to certain eyes than it appears now to ours, are certainly not drawn here for nothing (257-258).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 7: Turnkey

Tom is indeed at the end of his financial rope, as he can pay neither the turnkey nor the boy bringing him ale.

A Rake's Progress: Plate 7: Turnkey

Dobson

In one he is a poor distracted wretch . . .pestered by the unpaid pot-boy (43).

A Rake's Progress: Plate 7: Turnkey

Lichtenberg

A boy, or whatever sort of creature it is (for in the formation of his physiognomy insolence seems to have been working for at least a quarter of a century), has brought him the porter as requested, though for the time being only to look at. Without barter the poor wretch, languishing for a drink, will not have a taste of it, and there is nothing left to barter! Even the shoe buckles seem to be only mourning buckles, whose lacquer or blueing has already been mourned away. Behind him stands the executioner under-turnkey! To judge from the book which is resting on his arm, he wants to call in the garnish money, the 'welcome' from the prisoner. The face, which the fellow also offers for sale, seems to be one of the best which he is capable of producing, in the interests of the transaction. It is a pity that Rakewell does not see it, but he would not have been able to buy it in any case. The insolvency which can no longer pay for a can of beer will probably be content with such faces as insolence presents gratis. Does the reader notice the conclusion, in forma iuris, which is drawn here? A poor devil who has been put in prison be- cause he cannot pay is required to pay for being in prison. Just like this, a few years ago, did the French deal with the good city of Worms, merely because, as they said, that city had offended the good city Worms herself (255-256).